Two of the key communications goals of a think tank are being heard by the right people, and your information being found easily when needed.+ Historically, organisations seeking policy influence could pursue these goals in separate ways – the former through use of events, media engagement and public affairs activities; the latter through the availability of publications in key content repositories. However, on the Internet, being heard is key to being found – and thus ‘being there communications’ supports both goals.

Traditional communications functions – how to be heard and found

One of the key ways of a research message being heard has traditionally been through the media. Television, radio and the press can reach a person in their home, and many have developed routines and habits around certain trusted broadcast programmes. Organisations aiming to influence policy could decide to engage with outlets based on their audience profile. Even today, the BBC Radio 4 Today programme is a key channel for think tanks releasing high-profile reports, because it is listened to by a large number of the UK’s most influential people and decision-makers on a daily basis. However, getting information onto an influential channel like this isn’t easy.

Another route for getting heard has been to host events to highlight work to particular audiences. ODI, for example, has a long history of hosting events in Parliament, as well as a programme of engagement with parliamentarians and the civil service directly. However, participation in these events has been limited inevitably to those within the vicinity of the venue.

Being found – getting information into the hands of those seeking research on a subject – has been linked traditionally to publishing in books and journals that are disseminated through libraries and bookshops around the world. Historically, if a think tank achieved publication and could distribute to libraries, there was usually a good chance of being read by interested parties. But this distribution channel has always been relatively expensive, and the likelihood of a book being read was often limited more by whether it was easily available to the consumer or not. Indeed this is still the case in many parts of the world.

Traditionally, one organisations’ success in being heard could raise their profile and subsequently support their chances of being found, and vice-versa. But the two aims could exist independently: it has been possible to be heard through the media and in government, without publishing and distributing. Equally, an organisation could influence the international agenda through publishing and disseminating to libraries alone.

Digital disruption of these functions

On the face of it, the Internet makes both being heard and being found easier for think tanks. Instead of working through central broadcast channels or libraries, an organisation can go it alone, fulfilling the roles of content producer, broadcaster and content storage facility. Two powerful technologies are key to this:

- For think tanks wanting to be seen, email has been the main broadcast medium of the Internet, allowing direct dissemination to large numbers of contacts. People sign up to mailing lists in increasing numbers, and wade through – or ignore – masses of information sent to them. A 2010 study found 83% of workers use email as a primary source of communication.

- For think tanks wanting their information to be found, a website offers the chance to publish research and organisational information quickly and cheaply. Importantly, this is supported by search engines that quickly find and return research results from across the globe at the click of a button.

By using these technologies, think tanks have seen a massive expansion in their capability to distribute information, and in the likelihood of their content being found by interested audiences.

Unfortunately, think tanks aren’t the only organisations that have benefitted from the opportunities brought by the Internet. Everyone can publish on the web or broadcast by email. Information overload on both platforms is endemic – 57% of email users claim to be overwhelmed and the web holds a mind-boggling 14 billion indexed pages. This ease of dissemination makes messages from one organisation harder to pick out from the crowd; and potential competitors are equally able to use the Internet to attain global reach. With more organisations encroaching into one another’s traditional communications space, the right digital strategy to be heard and found is key.

‘Being there’ communications

‘Being there’ communications is an attempt to bring a more strategic vision to digital distribution of communications outputs by explicitly linking efforts to be heard and found. Content and links are placed on sites that are visited by key audiences, rather than expecting these audiences to come to an organisational site. As a result, more people are reached, who can then share the content through their own networks.

ODI is implementing a ‘being there communications’ strategy in the following ways:

- Where possible we repurpose content for top media sites. For example, a Guardian blog written by ODI Research Fellow is based on an ODI paper available on the ODI website. The Guardian blog has opened up the research to more people, and attracted 72 extra ‘tweets’ and 20 Facebook ‘likes’.

- We aim to get our staff and researchers creating original content for top specialist sites in the appropriate fields. We’ve encouraged researchers to take on contributor status on popular blogs, for example Claire Melamed on the Global Dashboard, or even my own blogs on onthinktanks.

- We have a process of adding research findings to Wikipedia and other relevant knowledge hubs (in international development Zunia and Eldis are good examples).

- Our pages on networks like Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn offer selected views of our content. Many more people ‘like’ or ‘tweet’ content that comes through their stream this way than they do on the ODI site.

- We offer RSS news feeds not just so that people can receive news from across the web quickly and easily, but also to facilitate automatic dissemination across multiple sites. Both Facebook and Twitter are automatically updated by tailored RSS feeds.

- Of course, as long as email still remains a core part of people’s lives, it is a powerful ‘being there’ tool. We’ve overhauled our email services to ensure people can easily sign up, and are looking to increase tailoring of emails by subject. We also send out email alerts to subject mailing lists, and encourage researchers to email their contacts with details of new publications they’ve written or events they’re involved in.

Benefits of ‘being there’

‘Being there’ is an iterative, not transformational, process that makes sense in both the short and the long term.

In the short term, increased sharing of content (being heard) is good for search engine optimisation of your site (being found). Why? Because in a world of information overload, trust is key to which information is selected by users. One of the biggest companies in the world – google – came from nowhere because it could help people find things better than others could. It did this in a very clever way, by using complex algorithms to try to judge the trustworthiness of sites and content, and then highlighting it.

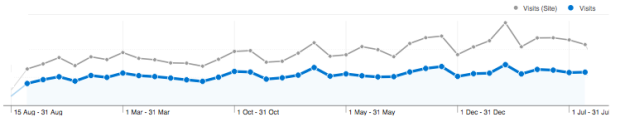

The links you’re placing on other quality sites back to your content will help you maintain or improve your search engine ranking, and drive more traffic to your site.

In the longer term, people faced with ever-increasing amounts of content will become more discerning about how and where they interact with information. No longer will ‘being heard’ and ‘being found’ be either/or options, as organisations that aren’t heard will be discriminated against in terms of being found.

The network leading the charge on this is Facebook. Facebook’s initial interest was as a very well conceived and executed social network. Through Facebook, more information has become available than could be held in someone’s personal email inbox, but it felt easier to handle. The information available on Facebook is very much skewed: a user sees only a small percentage of what is available, selected according to those people and organisations that users indicate they trust or are interested in by commenting or another form of engagement.

Though Facebook has been at the forefront of this change process, it is one of many platforms that users may choose, including Google+ or a more specialist site based on Ning or another niche network tool. Google is already learning lessons from Facebook, by integrating more information on activities from social networks into search algorithms. Whichever network or site your audiences are visiting, the basics will remain the same. Using well-thought through engagement is key: to be heard and be found you’ll need to be there, in the middle of your audiences’ streams and lives.

The next post in this series describes a ‘cradle to grey’ content strategy. If ‘being there’ communications outlines the channel messages are delivered through, this blog looks at the content of the message itself, and how the Internet is changing both the format and time horizons for which a message can be relevant.