[Editor’s note: This article is also part of a series on Think Tanks and Video]

A few years ago I wrote about communications channels and tools for think tanks. The list was not exhaustive but it presented a rather broad set of options for think tanks to consider.

One of the most interesting elements of this way of looking at communications was that, rather than being focused on a specific policy objective and developing a strategy to achieve it, the implication was that think tanks ought to keep going, ever ready to jump at any opportunities to make a difference.

John Young at ODI used to call it ‘strategic opportunism’. Somehow this concept, which we used quite a lot in the ’00s at ODI got lost in the ’10s. We started to focus a lot more on strategic planning, theories of change, SMART objectives, etc.

But this concept is worth considering once again. Rather than obsess with detailed communication strategies I suggest:

- Focusing on developing the ‘right’ portfolio for your think tank,

- Building the appropriate (and most competent) team possible, and

- Being ready.

This recommendation made me think of an Orchestra. I first tried this idea on a group of communicators at a workshop in Dhaka a year ago. I imagined the head of communications like the orchestra’s conductor. Conductors have to make sure that all the musicians in their orchestra follow the partitures but he or she can also control the intensity, volume, and rhythms of the piece (I think this is how it works, music is not really my strength). The conductor also has to ‘read’ the audience and call for small changes in the way the piece is being played: more violins, more percussion, less winds, more winds, etc.. The conductor must make the best use of the human resources and the instruments he has sitting before him.

Every time the orchestra plays, it also practices. Each musician practices, too. As part of a team and on their own. They have to be at the top of their game individually and as a team.

The same is true for communication teams. Think tanks need to keep their public (the audience) engaged for prolonged periods of time. It is not good enough to get their attention once, at a press release or an event, never to engage with them again. They must keep journalists coming for more, reporting on their ideas and recommendations; policymakers engaged in policy discussions over several policy cycles until the right policy window opens; other researchers involved in debates; etc. Their ideas have a greater chance of informing policy if they remain relevant and on the agenda for longer.

Heads of communications (and in fact the think tank as a whole), therefore, need their musicians to keep playing. To keep producing excellent communication outputs that they can combine to make great music -engaging music, popular music, interesting music.

Back in 2008 I had the chance to lead a programme that looked at poverty and trade in Latin America. We called it COPLA (Comercio y Pobreza en Latino América). The name, COPLA, came from the word copla, in Spanish, the couplets of popular songs. We imagined that influence was similar to the effect that catchy couplets have on audiences who join in and sign along with the band.

The objective of a think tanks is similar. It want others to ‘sing their songs’ and make them their own.

How does orchestra communications work?

First, we must stop worrying about strategy and strategic documents. We must set aside log-frames and theories of chance (the tool, I mean; not the theories of how change happens: like here or here). Rather, we must develop three things:

- A portfolio of communications channels and tools

- A communication team -with clear ownership over each one of the channels

- Tactics or rules to use these resources

What comes first? I do not know. There has to be a negotiation between all. The choice of channels and tools will certainly define the final composition of the team. But the team can have an effect on the channels, tools and tactics in the long run.

Of course, the think tank’s resources will play a role, too. The answer to the question: how much is the think tank willing to allocate to communications? will be critical in this process.

And, certainly, this process will need a leader, a head of communications, a conductor. Developing a strategy before having a head of communications is never, in my view, a good idea.

The portfolio

The portfolio is the universe of communication tools (for each channel: publications, media, events, and digital) -aside from direct personal communications- that the think tank is willing and able to use. Of course, think tanks won’t -and shouldn’t- use all of them all the time. This is just the potential set of tools that could be used. I wrote about this before:

Not all the tools are appropriate for all think tanks or centres. Each organisation must choose the most appropriate mix. Similarly, not all tools will be useful for all projects or initiatives of the centre. The right mix must be chosen in this case, too. The following questions can guide this process:

- Does the centre have the resources to effectively deploy all the chosen tools? For example: Does it have media skills to deal with an important media strategy? How many events can it organise in a week? Does it have reliable access to the internet? Does it have resources for printing its publications?

- Are the tools sufficient to reach all of the centre’s main audiences? Are any not being reached through the choice of tools and channels?

- Do they offer the right balance between content and outreach? In other words, is it all repackaging or is there sufficient original material to carry the argument for a significant period of time?

- What will be the best way of keeping the centre’s arguments and ideas on the public agenda for longer?

- Are the tools linked to and supporting each other or are they being deployed independently and in isolation?

Each tool needs to be described in detail so that anyone (not just the communicators) can figure out how to produce and use them. Remember that most think tanks won’t have dedicated communications teams and some of their researchers will have to do some of the communications work. This is a good format (summary version):

Name: Policy Brief

- Description and use: A policy brief focuses on providing actionable recommendations to its main audiences drawing from research presented in working papers, research reports, etc –as well as other third-party sources.

- Audience and style: It is aimed at the specific policy audiences it targets and so should be written taking into account their own characteristics (level of knowledge/agreement on the issue, organisational culture, policy opportunities, stages in the policy cycle, etc.).

- Format: A policy brief should be about 2 to 4 pages long. It should include text boxes and graphics and a relevant image for the cover.

- Peer review and quality control: Policy briefs should be peer reviewed by members of senior management and possibly include inputs from members of the target audience. They should be signed-off by senior management.

Intranets are very useful for this. They make it possible for anyone in the think tank to find this information as well as examples of the tools and templates to use.

For excellent ideas of the channels and tools you may want to visit WonkComms and its LinkedIn Group or my post on channels and tools that has a fairly extensive list. The Dhaka workshop posts also include examples from Bangladesh and Pakistan.

The team

My advice is that every channel requires an owner. This does not mean that every communications team needs to have a minimum of 4 members. Or that a think tank will necessary have to have dedicated comms staff -this may simply not be possible for some. But it does means that each channel should have a name next to it.

There are potential combinations to consider:

- Events and media can go well together so could be managed by the same person.

- Digital and publications could work, too, as more and more publications are produced in digital form.

- Directors or heads of communications are frequently drawn from the media and so they often take on the media channel

- Even some researchers and administrators for the much smaller think tanks could take ownership over some channels. Office administrators could manage events, for instance.

Why is this important?

First of all, the think tank, and the head of communications more specifically, the conductor, needs to know that the pipelines for each of the channels are being carefully managed. When a window of opportunity has been identified (e.g. a budget statement or an election -usually with a set date; or a catastrophe or crisis -which may create opportunities to join or lead a debate) the think tank wants to make sure it can get there with all the communication tools it needs to make the biggest and more prolonged impact. It cannot just say: oops, we missed that one, well, maybe we’ll have the publication for next week, but thanks for coming to our event.

Secondly, owning a channel gives a person the chance to practice. Some think tanks prefer to have communication officers (or staff charged with communications) at the project level. This means that this person might get to do one or two reports, maybe two events, possibly tweet a bit, a blog post or two, at most, in one year. There may be 3 or 4 people ‘working on comms’ at the think tank but none focusing on it or any one channel enough to get good at it.

Instead, centralising (to a decent workload) the communication function or at least assigning responsibility of each channel on an individual, gives them the chance to practice, learn and excel. They can even make a career out of it. An events manager/officer can find him or herself in pretty high demand after a few successful event series. And a digital communications manager can, more and more, find him or herself sought after other think tanks to lead their communications teams.

Finally, ownership over a channel gives the head of comms and the researchers a focal point with whom to work. It is clear to all who is in charge of the website, or publications, or events. It makes it easier to work across sectors, levels, and timelines. It also gives providers a focal point. Most think tanks will use copy-editors, designers, publishers and other services providers. It helps if one person in the think tank manages the organisation’s relationship with them.

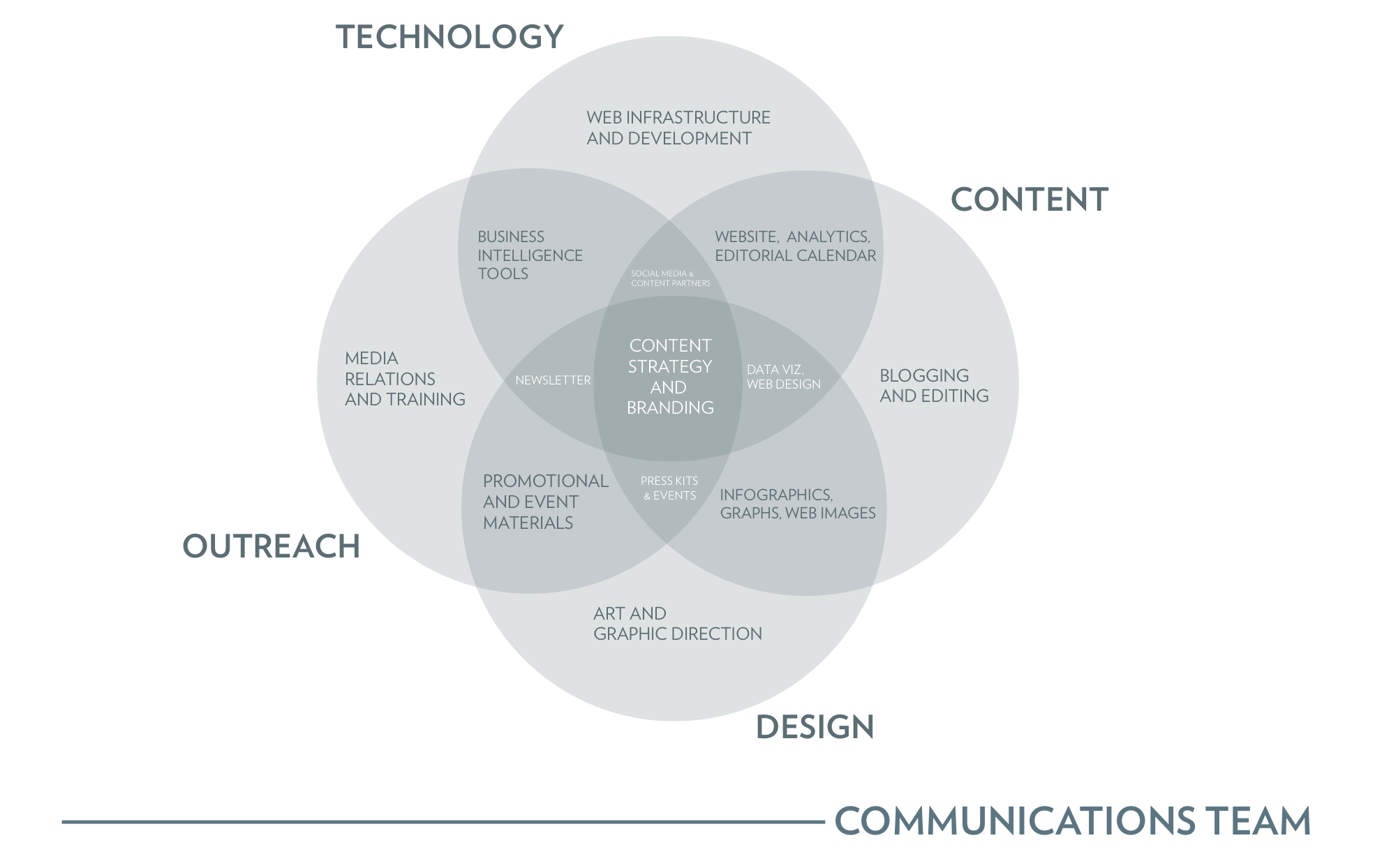

I found this excellent diagram by Joe Miller, VP Communications, The Century Foundation (view team diagram below). It describes how some of these issues come together: the tools (technologies), the content, design, outreach (tactics, in the next section) and the team.

Tactics and rules

The tactics and rules help at two levels. First, they help with the auto-pilot mode that the think tank needs to have. For most projects and research work, the think tank needs to get on with business as usual. The comms team should not need to strategise much for most of what a think tank is doing at any given time. So all researchers should know that, for instance:

- You cannot publish a paper without an accompanying blog post

- Or that you cannot have an event that is not web-streamed, does not have a web-page with all the materials online before the event, and does not include an event report within 24-48 hours

- Or that media appearances need to be accompanied with a Tweet of the upcoming interview, a Tweet while the interview is on air and one linking to the recording, video, or printed version.

Rules can also help think tanks at more strategic levels. There will always be a few (there should not be too many) policy issues, ideas, or even policy windows that should focus think tanks’ attention. These need to be targeted with special tactics to be deployed over prolonged periods of time to achieve certain specific objectives. For these, the comms director and others (including the comms team and researchers) need to think about the best way of using the think tank’s communication portfolio -its entire orchestra.

Having rules that are used all the time will come in handy when it comes to asking ‘what works’. Rules help us test and learn. I wrote about this after a workshop in Dhaka:

Rules make it possible to test new tools. From set to set [e.g. from event to event or from publication to publication], the think tank can make small changes –introduce or remove tools- to see what they effects are. It can, for instance, organise an event using EventBrite and see if it makes a difference; or try to contact journalists via Twitter instead of email and see if more show up.

Examples of rules to be tested are:

- Working paper(s) and policy brief(s)

- Event and Twitter and blog

- Research Report and blog and interview and event

- Event and video and Twitter and Event Report (why not on Storify?) and interviews and publications

Here is an example from CPD in Bangladesh:

Reaching the Top of the Charts

Think tanks are in the business of popularising ideas. Their purpose is to encourage others to adopt their ideas or the ideas of others that they agree with. They compete with many other think tanks but also with other organisations with very clear advantages over them:

- The media can reach many more people than think tanks -in fact, think tanks need the media

- Political parties can reach positions of power and ultimately set the agenda and make policy decisions -think tanks need them

- Businesses and business lobbies do not need to worry too much about the ‘evidence’ when it comes to advocating for their interests -and think tanks need their money

- NGOs are much better at mobilising people and running far-reaching campaigns that think tanks can be -and NGOs can certainly help to mobilise people around a think tank’s idea

- Universities have, whether they deserve it or not, a certain aura of credibility that can open many doors while think tanks are often seen with suspicion -and think tanks need universities’ ideas, spaces, and graduates to survive

So think tanks best chances are in getting their ideas and their researchers into the right places and onto the right agendas for as long as possible. Communications as an Orchestra should help.

One way of achieving this is to ‘write and publish music’ for maximum impact. And to do this we need to pay a great deal of attention to how we resource, organise, and use each of the tools we have at out disposal to achieve the objectives we’ve set for the think tank.

This is not the same as having a theory of change for your influencing efforts; it has little to do with the length of your communications strategy document; and certainly nothing to do with the number of workshops you attend to learn how to communicate research.

There are three elements I have gathered over the years that I think can get as close as anything to guaranteeing that you will be doing all you could do:

- Get the right people: Over the last year alone I’ve listened to many think tank directors and leaders complain that it is impossible to find the right people to lead (or work in) their communications departments. They argue that the people they have are either not skilled enough or do not understand the content of their work or the politics of their sectors enough. Of course, ideally they’d like to hire a 50 year old PhD former professor who decided to switch careers and become a communicator. There are two main flaws with this:

- Somehow, businesses far more complex than theirs manage to hire communicators and PR firms all the time. Bioengineering firms have to communicate to the public and to financial markets all the time and they manage to do so through consultancies and staff. So there must be perfectly capable communications professionals who could easily manage the communication channels and teams of organisations dealing with issues of public interest.

- Finding them is possible only if they give up their usual networks and opt, instead, for more formal, open, and professional recruitment channels. Last year, ACET for Africa in Ghana launched a call for a new head of communications and interviewed candidates across Africa and as far as the UK.

- Get your channels, tools, and rules in order: This is what John Young advocated for: be ready. This means having your portfolios and rules sorted out and a team of people ready to use them. Spending time on this is crucial for success. If you are ready then the right team will be able to take advantage of any opportunities that emerge -and even create opportunities. But to do their job properly, the think tank needs to…

- Learn to prioritise (or, from a different point of view, accept that not everything is a priority): Prioritising is a very difficult thing for think tanks -especially those who are large and cover a great deal of topics. Other industries do it much better. If you were a record label you would not try to get all the records you produce to the very top of the charts. You would not even try to make all the tracks in a record a #1. This is why they release singles or why they plan the releases of the records they produce through the year. The same is true for film studies who release films strategically for maximum box-office revenue. They may even sacrifice revenue in favour of Oscar Glory and release the film just before the cut-off date betting on nominations to attract moviegoers.

Prioritising

A final note on prioritising.

We can think of prioritising in terms of the opportunities we seek as well as the objectives we aim for. We cannot do everything all the time.

One useful way of looking at this is to focus on policy windows or policy processes. A single think tank cannot possibly try to be present in every single space available. It has to focus its attention on those it considers to have the largest impact and those on which they, themselves, may have the largest impact.

A policy window approach demands that think tanks plan their rules and tactics around the opportunities presented by these -and not driven primarily by what researchers may want. Policy windows allow think tanks to plan in advance: to develop the right content and the tools and tactics to be used in advance, to warn their target audiences and even prepare them in advance, and to practice, even, if the situation demands it.

Prioritising demands that think tanks have:

- Clear roles and responsibilities along the management structure. It does not work well when too many people have a say over this. Heads of Comms (or someone else, the director, possibly) must have a ‘final say’ and should be accountable to this.

- Dialogue. Think tanks sometimes organise weekly prospect meetings during which communications teams get together to discuss past and future policy windows, plans, and pipelines. According to Lawrence MacDonald, when he was at CGD in Washington, these were held in ‘public’ to encourage anyone to join. At ODI, these were help in private but with the participation of programme level comms officers (who worked for the programmes and ‘represented them’ at these meetings). Prospect meetings can be supported by frequent (weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly) formal and informal meetings of senior management (including communications) and the staff. Conflicts are less likely to emerge if there are plenty of opportunities to dialogue.

- Strategic, long-term, priorities: Think tank themselves can set out their own policy influencing priorities. These can act as a hierarchy to guide prioritising which issues, projects, teams, or researchers get more or less support from the communications team and its resources.

Previous

Previous