Communications is not just about content.

It’s about relationships. It’s about values. It’s about timing.

The digital think tank

Those of us who work in think tank communications have been slightly obsessed over the last few years with going “digital first”.

Mike Connery’s 2015 article The Digital Think Tank remains the best explanation of the reasons behind this shift and some of the changes we can expect. As Mike says:

Today, audiences are used to information finding them. It’s a model sprung from digital media, and one that privileges brevity, shareability and a highly visual approach to content.

So we’ve all spent an awful lot of time thinking about content and ways to deliver it.

At Soapbox, that meant that we spent much of 2015 writing, designing and building scrolling, media-rich, longform microsites – like this one for the International Rescue Committee.

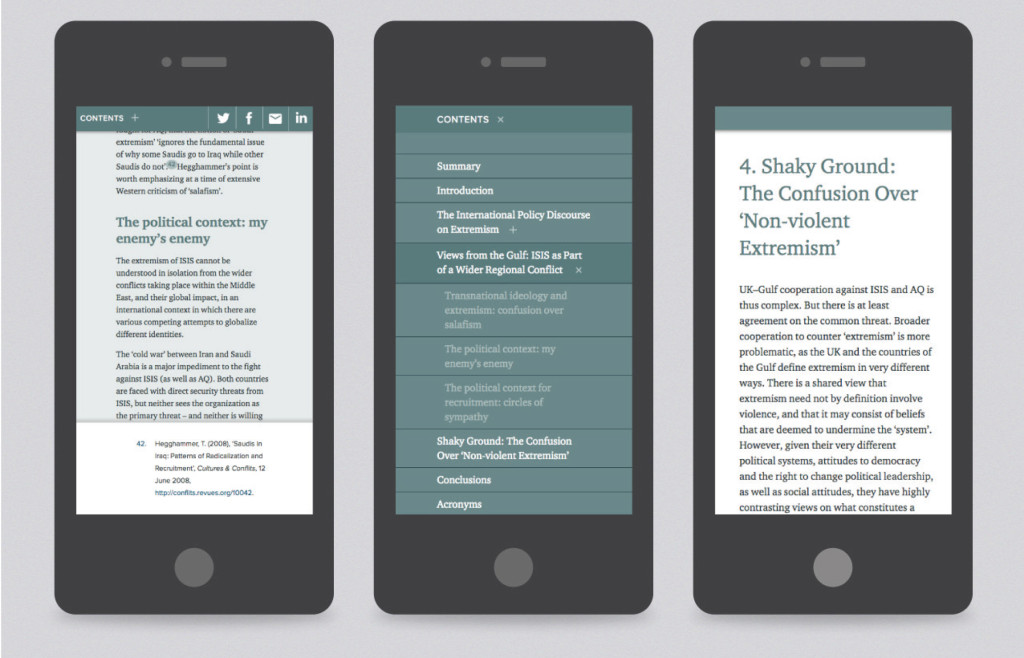

Then in 2016, we built several different ways for think tanks to deliver long-form research content from within their own websites. This included a multichannel publishing solution for Chatham House.

This year we have started rolling out websites built with modular content management systems, an innovation well described in a recent article by Joseph Miller:

You write, edit, and approve a single source of content. Since the content is modular, you can create different combinations of modules. And … you can push different content combinations to different platforms.

The first modular content management system we built was for the LSE’s Urban Age site. The latest is the new Nuffield Trust site, but there are others in the works, each one building on the last.

Digital first has unstoppable momentum and – while we have still have a long way to go before we are actually producing content in this way as standard – there is a fairly good consensus on what the content will look like when we get there.

But, as I said, communications is not just about content.

Beyond government

In his 2016 RSA lecture Matthew Taylor offered a critique of what he dubbed “the policy presumption”:

By this I mean an assumption among ministers, civil servants and policy advisors, but equally all of us … that, on the whole, the most effective way to accomplish social change is to pull the big levers of central government policy.

Yes, policy still needs to be evidence-based. But that is not sufficient. People are mistrustful of political elites. They feel let down and not listened to. In massive numbers, they are looking elsewhere for change. We are realising that successful policy involves engaging with values, feelings and relationships – and with the lived experience of people who deliver and receive public services.

Policy impact often means changing the conversation gradually over years but it also means acting opportunistically when the time is right. And it can mean building coalitions to stand up for what we believe and challenging those in power when they act against evidence and against progress.

Politics has changed. The public perception of politics – and by extension policy – has changed. The ways that policy is delivered on the ground and that services are designed has changed.

In a recent publication on think tank impact, Julia Slay writes that:

Some think tanks are beginning to look beyond government as the source of change and towards other organisations and activists that can build grassroots support among the public, campaigners and organisational partnerships.

Think tanks have always been good at public affairs and media communications – working directly with political decision-makers or through the media to create impact. But we’ve rarely been very good at capturing the public imagination. And we’ve never been very good at mobilising mass support.

That’s because we never had to. Until now.

Going pro

I believe that digital first is actually part of a wider movement towards the professionalisation of think tank communications which has been going on for over a decade now – a kind of ongoing revolution in think tanks comms.

I often tell young Soapboxers that when I started working on think tanks reports they were all A5 size, all typeset in Times New Roman and all had a picture of Big Ben on the cover. It’s only a partial lie.

Design standards in think tank reports started improving dramatically about ten years ago.

About seven years ago we started trying to present data in more imaginative, accessible ways.

Five years ago think tanks started to take their visual identity more seriously.

Three years ago we started getting report content online in full – the beginning of the long death of the PDF.

This year modular content is taking off.

Constant change. Constant progress. A constant move to more professional communications.

The change is driven not just by the digital revolution in content, but also by the changing ways think tanks create impact and the much wider range of audiences we seek to engage.

We need to take a step back and ask what kind of communications framework can meet these challenges.

What is the next step in our permanent revolution?

We need to talk …

I’m going to discuss four concepts which are commonplace for professional communications in other sectors, but which think tankers have struggled to get to grips with, ignored or actively turned up their noses at over the years.

Corporate communications started taking these concepts seriously in the 1960s and 70s, with big charity and political comms not far behind. So it’s time we got with the picture. I’m afraid we need to talk about:

- Brands

- Markets

- Services; and

- Campaigns

The good news is that think tank comms has been secretly making strides in all of these areas for at least ten years now – but we need to get even better, we need to join up the dots and we need to come out of the closet as communications professionals.

Brands

For many modern corporations the bulk of their equity is vested in their brands – no wonder they spend billions promoting and protecting them.

By contrast, in 2005 when I designed this logo for IPPR (let’s call it the classic IPPR logo), what happened was that IPPR’s then Director, Nick Pearce, stood behind me for about fifteen minutes while we looked at different colours on my screen. Job done.

We’ve come a long way since then.

Wally Olins, who more or less invented the modern practice of branding, used to say that branding is about delivering on promises:

The only requirement of a symbol is that it have substance underneath: The first thing to do is to try to establish the substance

In other words, branding is about substance. It’s about giving people something they can trust.

And as a think tank, you need people to trust you.

When we worked with ODI in 2012, this was the first think tank rebrand I had been involved in that actually took this notion seriously. We tried to create a brand that reflected the values of the organisation, its personality and unique positioning. We based the visual identity on research with external stakeholders and a lengthy internal dialogue with the organisation. We wanted to make a brand that would help it become the organisation it aspired to be.

Nowadays, that kind of process and aspiration is normal in our branding projects. But we are starting to take it further, producing full-scale brand strategies alongside visual identities.

If you really want to take your communications to the next level, then you need to understand your organisation’s personality and narrative, what you are promising your audiences and your value proposition in the market. And you need a strategy to maintain, reinforce and grow these positions.

You need to take branding seriously.

Markets

It is not a very profound observation to note that different groups of people will respond to different types of communications across different channels, but it is an observation that think tanks have struggled to get to grips with.

Thinking about audiences or markets has often not gone beyond the superficial. “People have short attention spans, let’s give them an infographic” is a typical brief from some of our clients.

We need to do better. We need to segment our markets.

Think tanks are increasingly asking us to create audience strategies for them, mapping different markets, creating personas and user journeys and making suggestions that influence the type of communications produced.

On Think Tanks TV produced a short film about the New America think tank and their work to communicate education research to different audiences: parents, educators and policy makers. The overall policy message to each group is the same, but New America’s website lets users easily navigate to resources and actions that are tailored to their particular perspective.

Which brings us to the need to involve users in the creation of our outputs. Thankfully, these days user testing of websites is seldom seen as an optional extra, by think tanks, but we can take user-centred design much further.

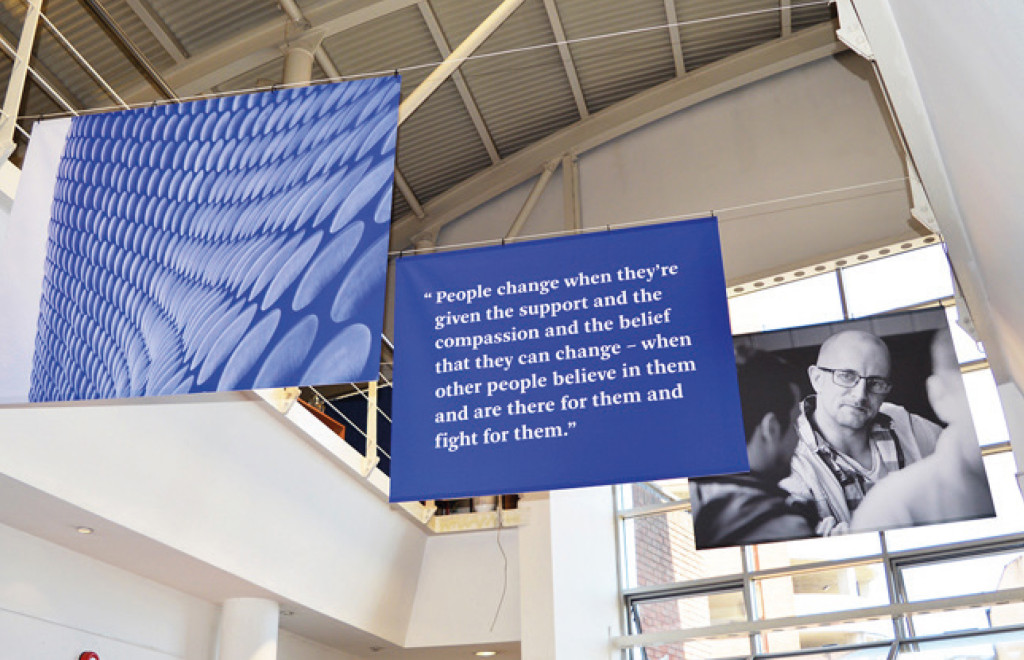

We worked with the Making Every Adult Matter coalition on a research project about people with severe and multiple needs. The outputs were codesigned with actual service users, and culminated in an exhibition at the Centre for Voluntary Action in Birmingham rather than a conventional research report. The exhibition ran for five months rather than the planned six weeks. It engaged thousands of service users and practitioners as well as local policy makers.

We not only need to understand our users, we need to get out and actively engage with them and create alongside them.

Services

Thinking about markets in this way can help us reconceptualise our work as researchers and communicators around the idea that we are providing a service.

Our purpose as think tanks is to carry out research and come up with ideas that change policy. Another way to look at that is that we are carrying out a service for those who need or want policy to change. These can be policymakers, practitioners, funders or the wider population who rely on public services.

So what do we owe to our service users? What service are we offering?

- We owe them our ability to conduct research and communicate its findings.

- We owe them our ability to come up with policy ideas and solve problems.

- We owe them our contribution to policy debates and our ability to convene and provide a forum for those debates

- And we owe them factual information and data as well as an informed opinion.

I would argue that once we conceptualise think tank work in this way, as a service with users, it becomes entirely impossible to defend any kind of “ivory tower” model of research whereby clever researchers lock themselves away until they are ready to come out and deliver their brilliant ideas to political elites.

Regular contributions and day-to-day engagements in policy debates are the very essence of the service think tanks are providing.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation recently commissioned the service design agency Snook to rethink their communication functions as services to their users. Instead of handing down communications from on high JRF are seeking to maximise impact by asking what communications are actually useful to different groups.

We will be seeing the results over the coming months, but one early example of the insights gained is that particular groups would like to have advance information on what reports are coming up so that they’re better prepared to respond. This included politicians who wanted to be ready to amplify and react to JRF’s messages.

As a result, JRF have already added a “what’s coming up” section to their weekly newsletter. It’s a simple change that seems obvious in retrospect, but one that could make a big difference.

Campaigns

You may be worried that all this talk of brands, markets and services means we need to create a large volume of outputs. A large volume that you can’t afford.

Structuring outputs around campaigns – and by this I mean communications campaigns, not political campaigns – not only allows us to increase impact by banging on about the same simple messages day after day but also to bring efficiencies and economies of scale to our content production.

To produce content that can be used across multiple channels for multiple audiences you need to start with two things:

- a set of key messages; and

- a set of content that illustrates and supports those messages. This can be infographics, videos, case studies, photos, audio – whatever does the job.

This is the the same point as the modular content management systems we mentioned earlier – you create content modules once and then put them together in different combinations for different platforms.

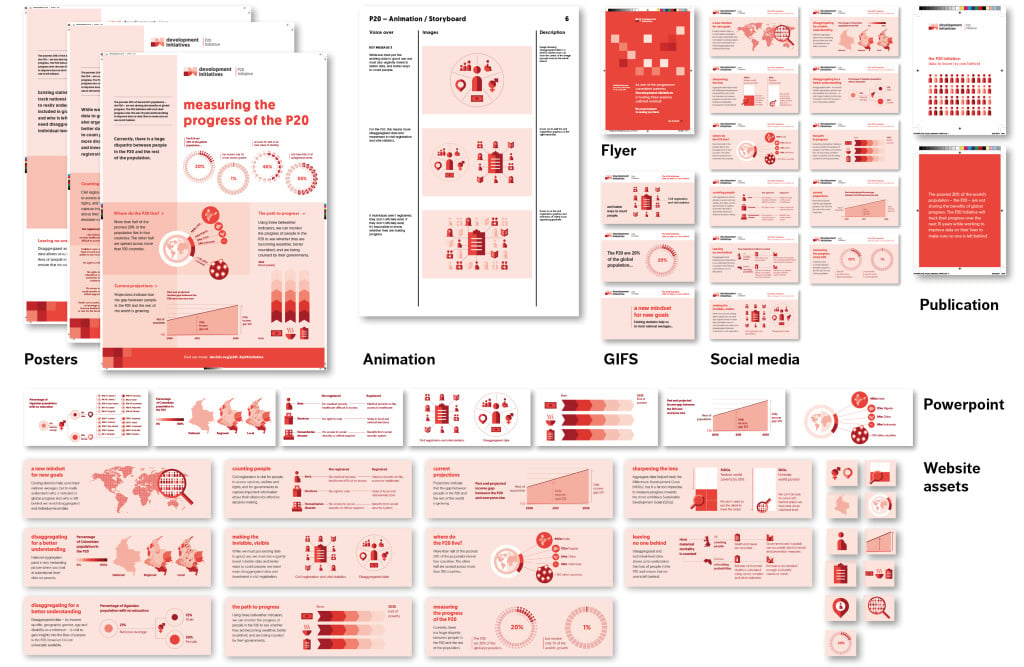

Development Initiatives recently launched their P20 campaign looking at the world’s poorest 20% of people. We worked with them on to refine a set of simple key messages and used their data to create supporting infographics.

We then put these together in different combinations to create posters, an animation, a publication, powerpoint slides, animated gifs for Twitter and Facebook and static infographics for the website.

And we could do even more if they wanted: they could have an exhibition, or a scrolling microsite or project the infographics onto the Houses of Parliament – anything really.

The point is that once you have the foundational elements then the rest is relatively easy and cheap.

If you structure your content around campaigns and plan carefully, then you can serve a range of markets while maintaining economies of scale.

Brands, markets, services and campaigns

Think tank communications are professionalising and have been for some time. This is driven by the digital media revolution but also a revolution in how policy is made, how it is experienced and how we can generate impact.

Adopting a professional communications framework can help us define realistic and objective goals for our comms activities and better monitor impact:

- What percentage of stakeholders can accurately associate our brand name with our value proposition?

- What percentage of a particular target market have we reached?

- How many citations does our output in a particular policy debate generate?

- How many people took a particular action as a result of our campaign?

We can start to ask these kind of questions and generate actionable data as a result.

We need:

- Communications that build trust in think tanks by reinforcing their values, and positioning.

- Communications that connect with their intended audience, or even better, are co-produced with the intended audience.

- Communications that contribute or assemble knowledge, ideas and opinions in ways that are useful and positive.

- Communications that are efficient and adaptable.

The next step forward for think tank communications is to start thinking in terms of brands, markets, services and campaigns.

Then we will have a framework to create communications – digital first and otherwise – that are well-targeted, values-driven, evidence-based and, above all, impactful.