[This conversation was originally published in part 1 of ‘Narrative Power & Collective Action’, a collaboration between Oxfam and On Think Tanks. All conversations were edited by Louise Ball. Download the publication.]

Aidan Muller is a journalist-turned-strategic communications and digital expert, majoring in political affairs. He has been a digital advisor in UK Government, including helping introduce social media to the Prime Minister’s Office at Number 10. He now leads Digital Strategy at Cast From Clay, a London-based communications agency founded in response to growing polarisation and the rise of political extremes.

We’re not saying sacrifice facts at the expense of narratives, there’s no reason why they should be mutually exclusive.

What are narratives to you?

Stories and narratives are what define us as humans. They provide the frameworks through which we view and understand the world.

There’s a great book by journalist Christopher Booker called The Seven Basic Plots. It identifies the seven narrative arcs in the history of human storytelling. Pretty much every major piece of literature, from The Iliad to The Lord of the Rings, fits within those narrative arcs.

The narrative arcs are storylines that we recognise and can identify with. They activate pre-existing neural networks in our brain that make us positively predisposed towards the stories we are being told.

That’s what narrative is, it’s a framework populated by stories. And the stories are the proof points of a certain narrative.

Some of the best stories weave multiple plot points together. So, it’s really powerful if you can tap into a number of plots and narratives that our brains are naturally predisposed towards.

The role of emotion

Those plots or narratives are devices that can help elicit emotion within whichever audience you’re trying to communicate to.

I am always careful about how I talk about emotion because it sends anyone who works in policy running.

But emotion doesn’t necessary mean bleeding hearts or a crying baby. Emotion is evoking something deeply human in your target audience. Anything that makes people relate to the story you are trying to tell and that creates empathy.

An interesting finding from our research was on the role of emotion in forming political opinions. Not only does emotion play an important role in how the majority of the population forms their political views, but that’s also true of policymakers.

We asked those working in policy and politics to what extent their heart rules over their mind in forming political views and 48 % said that it did.

So, think tanks and policy organisations need to think more about the role of narratives, framing and human storytelling. If they don’t do it for the public, then at the very least they should be doing it for policymakers.

Cast From Clay works with international NGOs, think tanks and universities to connect them with the public – to craft policy ideas into human shaped stories. In our conversation with Aidan, we asked him to tell us more about why this is important?

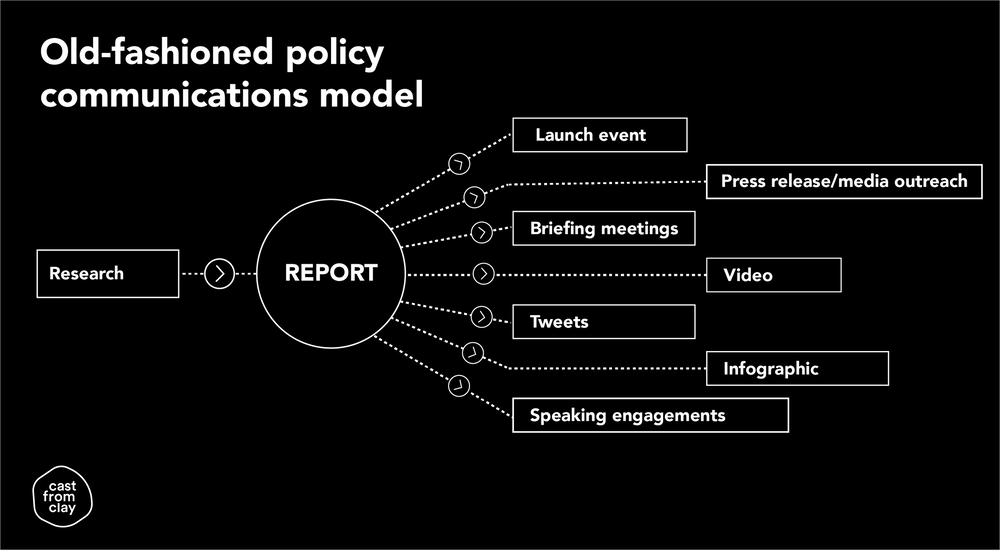

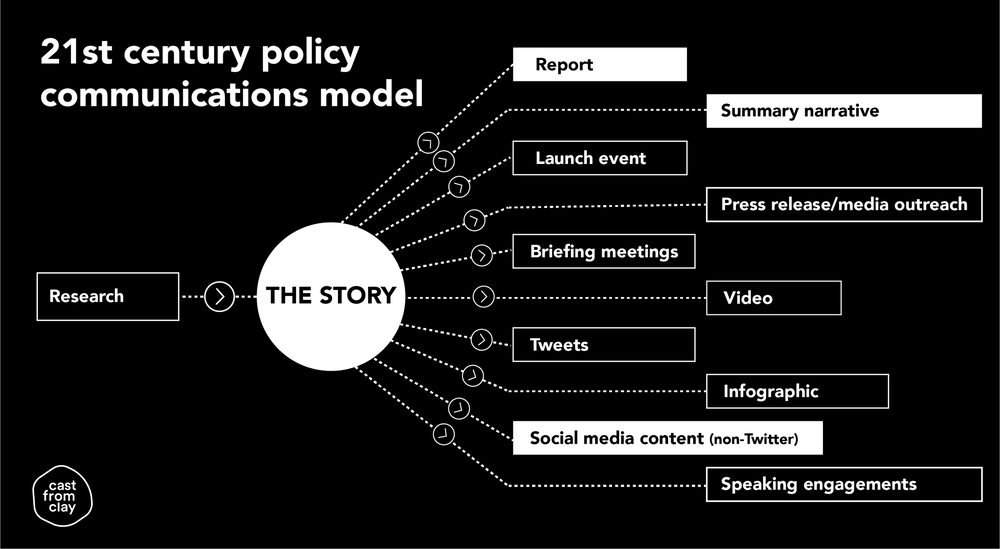

We are trying to get thinktankers and policy experts to think in terms of stories and narratives, because for years they have relied upon fact-based communication strategies – which don’t work.

We want think tanks to not just focus on a particular piece of policy, but to think about the broader framework within which they are telling their story.

You can have the best argued policy, with the best facts and evidence, but in the end it’s the best story that wins.

For example, in the UK European Union Referendum, the Remain campaign made a rational fact-based appeal. Whereas the Leave campaign told a story about plucky citizens rallying against an urban liberal elite and Brussels technocrats.

They provided a happily ever after scenario: ‘we will leave the EU and things will be better.’

Whereas the Remain campaign’s happily ever after was the status quo, and that’s not what dreams are made of.

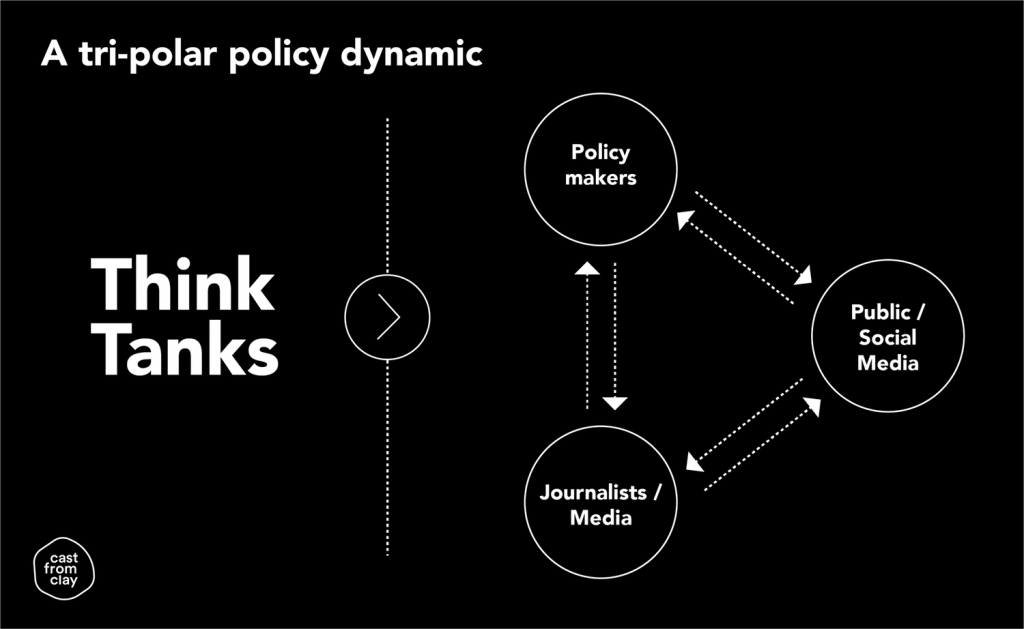

To policy experts we’re not saying sacrifice facts at the expense of narratives, there’s no reason why they should be mutually exclusive. We’re saying, you’re really good at facts, but let’s get better at narratives. Because, things have changed quite radically in the last 15 years. Previously the policy agenda was set by the policymakers and the media.

Today, if you want policy to change the reality is that you need public support, or at the very least you need the public to not be against it. The public outcry in the UK around the Dementia TAX policy which led to it being dropped is an example.

Pre-internet, facts were in short supply. Think tanks had the monopoly on facts, so they had a position of authority.

They don’t have this anymore and they need to adjust. In this way, the civic space for think tanks has changed quite radically.

Today, for every argument you want to make, you can go online and retro fit the facts to support your narrative. You can find a blog or obscure research that will back up the argument you’re predisposed to.

The disconnect between politics and the people

I think that anti-expert and antiestablishment narratives are symptoms of the same phenomenon: we’ve been so focused on the macro side of politics and economics that we have completely missed the micro side: the reality on the ground for people.

It’s all very well telling the general public that GDP is growing or unemployment has never been lower, but if they feel they are worse off, they aren’t going to care about what the statistics say.

Thinktankers aren’t adequately representing their constituency. They would probably say the general public aren’t their constituency. But the general public gives them legitimacy in the democratic system.

So if the general public feel that think tanks and policy groups don’t represent them, of course they are going to think that policies are made in the interests of that urban elite.

That’s what is contributing to the rise of populism and distrust of experts. If your narrative as an expert doesn’t fit the public’s lived experience, then at some point you are going to lose the battle.

Keeping the door open for dialogue

It’s useful to recognise that for the most part people want the best for their family, community, country. So often, when they oppose your views they are doing it in good faith.

That’s why it’s so important to understand both your supporters and those who oppose you.

And I don’t mean paying lip service to that idea, but really fundamentally accepting that their priorities or what they value might be different to yours, but that doesn’t mean that they’re wrong.

Respecting that they are coming from a different place but also trying to bring them along with you by changing the course of their narrative.

Build bridges for people

Pretty much all the research points to the fact that the best way to build bridges with people is keeping the door open for dialogue. And as polarisation grows this becomes more and more important.

It needs to be about redefining narratives, changing their course. If you take an adversarial approach and try to obliterate a framework within which people see themselves and understand the world, well that’s going to receive a lot of push back – or straight-out rejection.

This is important for think tanks, people working in policy, working in NGOs, to think about. Part of our message is: take the public as they are, not as you wish them to be.

We can try to steer them in a certain direction but they are who they are. If they gravitate towards a populist feeling, away from experts, we need to look at ourselves in the mirror and ask how did we get here? We need to take responsibility for this and change the way we do things.

That’s part of what we advocate for at Cast From Clay. We try to tell stories that help bridge the gap between the policy ‘elite’ and the general public.

But also, with our research, build a better understanding of where the general public are coming from and what their frameworks are, so that we can at least be having the same conversation.

Previous

Previous