Well, I guess I wouldn’t be wrong in saying that working in the Balkans is a synonym for dealing with perpetual crisis. Thus when a worldwide crisis hits, you are kind of prepared: relying on your accumulated know-how, adjusting your strategies and pulling out your secret policy weapons.

So, what was the COVID-19 crisis to Serbian think tanks? Was it ‘what the asteroid was to dinosaurs’ as Hans Gutbrod and Till Bruckner asked in March 2020? Or perhaps it was an opportunity?

I looked at the policy problems, proposals and strategies raised by four Serbian think tanks during the state of emergency, and compared them with the Government’s Economic Package to see how much they overlap. All four organisations I analysed – the European Policy Centre (CEP), the National Coalition for Decentralization (NCD), the European Movement in Serbia (EMINS) and the National Alliance for Local Economic Development (NALED) – are hybrid organisations that in addition to policy research perform other complementary functions like service-provision, education, advocacy and so on. I published the analysis in the Portuguese Journal of Political Science and present the main findings briefly here.

Let the data speak

The problem stream: since the moment the state of emergency was declared, think tanks started addressing important policy issues to be placed on the agenda. The key one was the negative impact of COVID-19 on the economy, but from different perspectives: while EMINS focused on the labour market, NALED stressed the concerns of the most affected sectors – such as construction, transport and agriculture. CEP and EMINS discussed the importance of regional cooperation and EU integration for Serbia to overcome the crisis, and the beneficial role of think tanks in such processes. NCD and CEP called for greater accountability and transparency of parliament and government, spotlighting problems of information centralisation and fake news.

Were these problems new? Not really. Although relevant, they were already on think tanks’ agenda well before the pandemic: CEP and EMINS’ focus on the EU as a way out of the crisis is in accordance with their organisational orientation. As a public-private association, NALED addressed the problems their members were facing. And NCD focused on increasing centralisation of governance, an issue they highlight in regular circumstances.

The policy stream: think tanks did not only highlight problems, they provided specific alternatives on how to deal with them. However, the robustness of these proposals varied significantly, from very general and vague to practical solutions. NCD and EMINS offered fewer and more general proposals. CEP and NALED (especially) were way more pragmatic, offering hands-on solutions and trying to impose themselves as relevant partners.

Again, the think tanks advocated for solutions that aligned with their existing strategic goals’ and used the crisis to push their ‘pet’ proposals. For example, NALED advocated for extending tax exemption for start-ups; NCD called for better cooperation between national and local governments; CEP stressed the importance of opening up government data to citizens; and EMINS invited civil society organisations from the region to foster their governments to act in a more coordinated manner.

Pushing forward these proposals: as windows of opportunity are rare and of short duration, think tanks need to act promptly, having their pet proposals ready to go as soon as the window opens. However, there was considerable difference regarding the speed of their reaction: NALED published 10 proposals for the government on how to mitigate the crisis a day after the state of emergency was declared. Whereas EMINS published its first COVID-19 content almost a month later.

Regarding the different strategies for ‘pushing’ their proposals, COVID-19 prompted think tanks to be creative in finding new ways to reach their audience. The most used tool was a media statement. NCD and NALED conducted online surveys, providing original data for their advocacy work. Self-recorded video blogs (EMINS) and online debates (NCD) were innovative ways used to reach the public, without violating social distancing rules. With the exception of NALED, think tanks used the names and reputations of their experts to attract attention, in different forms.

COVID-19: a window of opportunity

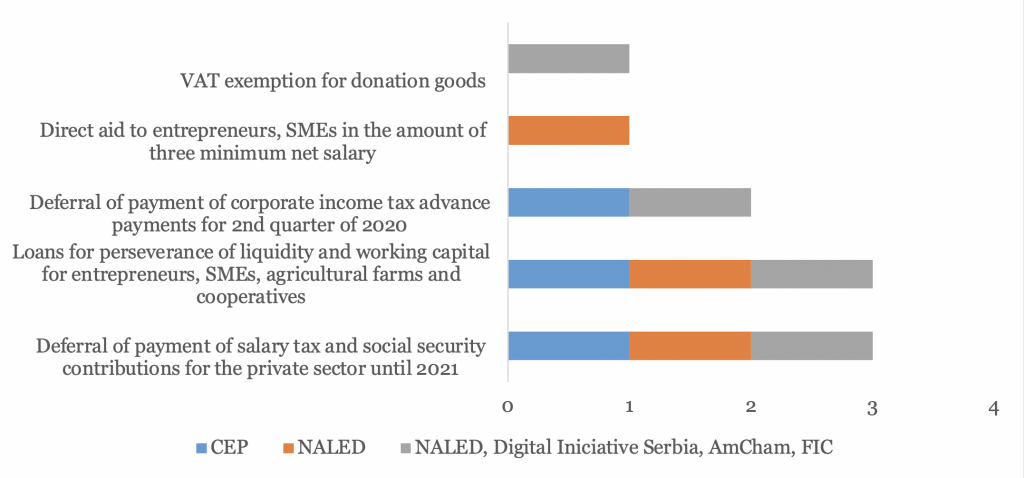

So, was COVID-19 a policy window for Serbian think tanks? The analysis found that five out of the nine government measures had been recognised as important and pushed for by CEP and NALED (EMINS and NCD didn’t come up with specific enough proposals to compare). So, I dare to say, yes it was. Some of their proposals fully matched the government measures and in others cases they had slightly different views on how to resolve the issues.

However, none of the five measures proposed by CEP and NALED (and introduced by the government) were their pet proposals. Rather, the proposals were tailored specifically to the COVID-19 situation. For instance, one of the nine measures adopted by the government was a temporary wage tax burden reduction. This was one of the measures proposed by NALED and CEP during the state of emergency. Prior to the pandemic, NALED had been advocating for a permanent wage tax burden reduction, but adapted its proposal in response to the crisis. And in the case of CEP, wage tax had not been on its agenda prior to the pandemic, but it adopted the proposal in response to the crisis. Thus, think tanks were quite flexible to shape their pet proposals in accordance with the new conditions, but also brave enough to deal with the completely new topics in order to stay relevant actors on the policy stage.

One more crisis, new lessons learned

COVID-19 was a crisis of global scale, but Serbian think tanks were prepared to respond. Based on the findings presented above, here are a few new lessons to be taken away from the Serbian experience:

- Act promptly, there’s no time to waste.

- Do not give up your strategic orientation, but be ready to frame it in line with the new context and deal with new issues.

- Be flexible in your advocacy methods and feel free to adjust your pet proposals.

- Make proposals specific, as generality easily dissolves in ‘policy primeval soup’.

- Do what you are best at, in a creative manner to ‘cut through the noise’.

Previous

Previous