Fundraising occupies a mythical status for me.

In one respect, I imagined fundraising to be some type of secret formula that only professional fundraisers could know and, I, as a researcher, could never figure out. Secretly, I hoped that this tasked could be outsourced to such a person because they would have all the answers.

In another respect, I assumed that fundraising was something that happened by itself. If your think tank was doing good work and was making a real contribution to the world, some rich benefactor or foundation would come by and shower you with money without you ever asking for it.

Obviously, I knew very little about fundraising. Which is why I signed up for the short-course “Re-thinking your funding model”, delivered by the On Think Tanks School. Little by little, the course demystified fundraising for me.

These are some of my reflections ushered in by the course, and subsequent conversations about fundraising in my organisation:

Myth #1: Core funding is the holy grail of funding

I idealised core funding as the be-all-end-all of funding. After all, core funding meant that you didn’t have to worry about the ebb and flow of funding priorities, and could concentrate on your own research agenda.

- Find out more about core funding: Life after core funding

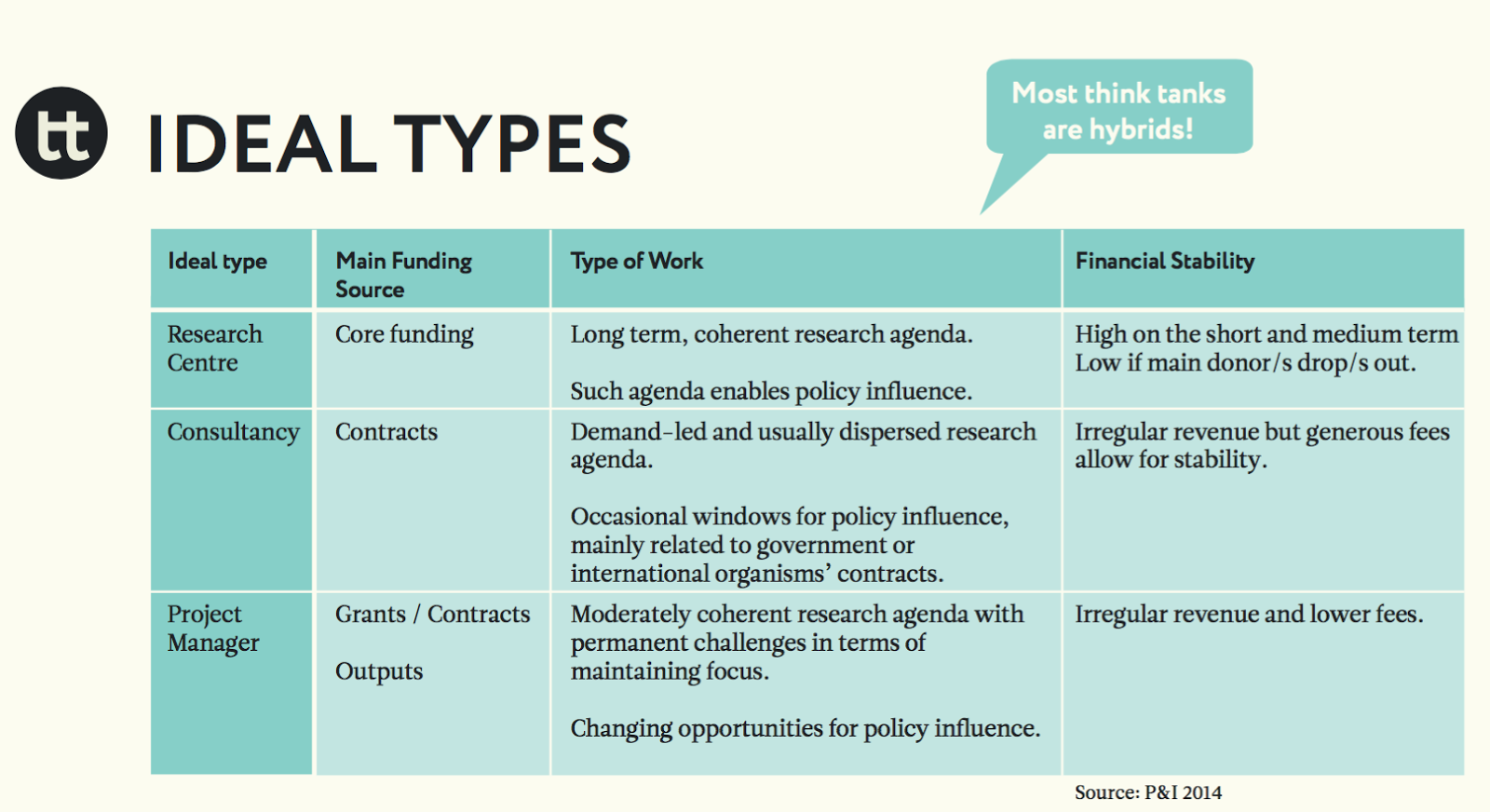

In reality, all funding models – from consultancy, to project grants, to core funding – have their pros and cons, and actually a sustainable funding model is one that doesn’t rely on any one model exclusively. What is most important is to have a diversified funding model, where the strengths and weaknesses of various funding sources can offset each other.

Myth #2: Think tanks shouldn’t ask for money

Many think tanks are afraid to ask for money. An initial conversation in the course was how asking for money has a negative connotation in many cultures and how we often see ourselves as either “beggars” (imploring others to grant us a favour) or “burglars” (stealing money from others who are more deserving). Personal attitudes about asking for money shape our “fundraising readiness” and block our ability to put ourselves out there.

You need a strong belief that the work you do is relevant and a strong argument for why your project deserves funding. Don’t underestimate the power of a good story – that is, the story of your impact: “Supporting us can lead to X, Y, Z in our societies/communities/world.”

As explained in the Manifesto for Non-Profit CEOs, fundraising isn’t all about asking for money, but “inspiring someone to see the world the way you do – with the same understanding of the problems and the same vision of how it can be overcome – and convincing them that you and your organization can actually make that vision into a reality.”

Myth #3: Think tanks only do research

Research is the core activity of most think tanks, however, when it comes to diversifying funding models, sometimes you need to think outside-of-the-box. Charging for outputs – one of the 3 ideal funding model types – includes products and services related to a think tank’s core work that could help to bring funds in. Examples of these outputs could include providing trainings, courses, as well as publications for a fee.

Other outputs could be produced in exchange for in-kind contributions. Enrique Mendizabal at On Think tanks suggested that a possible approach for them involves developing think tank relevant manuals for the various software and products that OTT uses, and approaching the companies for some kind of sponsorship in exchange for sharing these manuals with them – if not monetary, then a free year subscription. This helps to reduce overhead costs, which can contribute overall to the financial health of the organisation.

Myth #4: You need to develop a fundraising strategy before you can start fundraising

Importantly, fundraising seems to be mostly about trial and error. Sometimes no matter how much you prepare – developing a detailed fundraising strategy, meticulously deciding on your approach – sometimes you just need to get on with it. The worst that can happen is that a funder says no.

Even then, you can learn from this rejection for the next time. Take notes, adjust your approach, and understand where the connections are. You can even suggest to a funder that if your project doesn’t fit with what they’re looking for, to pass it on to someone who might like it.

Myth #5: You can start fundraising without an organisational strategy, or theory of change

While you don’t necessarily need a formalised fundraising strategy, it is really helpful to your fundraising if you have an organisational strategy – meaning something that outlines your aims, long-term plans, and vision for the future.

As pointed out by Jeremy Avins in his blog post, “Strategy is a fundraising necessity, not a luxury“, organisations think they have a “fundraising challenge”, when really they have a “strategy challenge” that is making fundraising difficult. That is because a clear articulation of how your organisation achieves change (and how it is going to monitor and evaluate this), gives the funders a better sense of what it means in practice to support the organization as a whole, and shows that the think-tank is thoughtful about achieving the most with its resources. As Avins sums up: “[An] organizational strategy is not just a luxury for well-funded think tanks. Strategy is a tool to raise more –and more flexible– funding.”

More of an art, less of a science – the key to fundraising apparently seems to just dive in – test, try, and then try again. The more concrete your steps, the less mythological fundraising will appear to be.