This article has been cross-posted, read the original post on Cast From Clay.

Stories are essential in policy communications. That’s because research is never released into a vacuum. We draw on cultural models to filter and organise new information, and they help us establish how relevant and important this information is.

Take an issue like obesity. In the UK, members of the public often draw on an implicit definition of health as the absence of illness. That means our starting point for discussing obesity is that it’s the ultimate state of bad health. There’s also a shared story that guides our thinking here: as one survey participant put it, “obesity does lead to health issues, diabetes, heart diseases. That link is there. It’s undeniable.”

So when we use the term obesity, we activate not only the shared definition but the story. The only way to avoid your policy message getting lost in the stories we tell ourselves and each other is – you guessed it – to tell a more powerful story.

Now, your communications strategy might focus squarely on policymakers (if it is, let’s talk). They’re short on time. They show “bounded rationality”, using mental shortcuts in the face of complex problems. For these reasons, policymakers want frameworks that help them understand the world, and make decisions. They want stories.

Filmmaking is daunting at first. Working with a professional filmmaker will help you tell high-value stories in a compelling way, so don’t discount these partnerships. But as a research communicator, you have privileged knowledge of the stories in your organisation that can make a human connection with your audiences. Meaning you could also have a go at filming yourself.

By starting simple in your shoot, capturing good audio, and adding interest, you can help your experts translate these stories into visually-compelling videos.

So here’s how to get started.

Focus on the subject, not the kit

Cameras can be expensive and complex. That makes them alluring and intimidating in equal measure.

But you have an exquisitely engineered and versatile camera in your smartphone. Consider using this to start your filmmaking journey. Then, instead of struggling to handle a new, complex kit, you can keep your attention on three elements of footage capture – framing, focus and exposure.

Pick a subject you find visually interesting. Consider how you want to position it within the frame. Do you want to use the rule of thirds, or is there another way you want to lead your viewer’s eye?

Here, both speakers are framed using the rule of thirds. Tom is framed off-centre. He takes up the left two-thirds of the frame. Natallia is centred within the central third, with a third on either side of her.

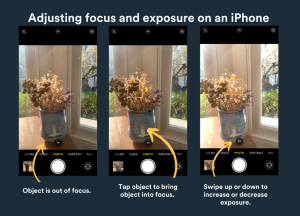

Now you’re getting comfortable with the idea of leading your viewer’s eye to what’s important using the frame. It’s time to take manual control of focus: consciously make things in the frame more or less visible, to guide your viewer’s interpretation of what they see.

The decisions you’ve made about focus now have consequences for how the subject and the scene surrounding it is lit. You’ll want to use your smartphone camera’s exposure settings to compensate. On your smartphone, tap once for focus, and a slider controlling exposure should appear.

The more you master framing, focus and exposure, the better you can show your viewer what you see. And you can get comfortable with this essential filmmaking skill right away, using a device you already carry around with you.

Good videos depend on good audio

There’s a saying in filmmaking: “people will forgive bad picture, but they will never forgive bad sound.”

As we’ve seen, you can get a lot of control over your picture without spending a lot of money.

When it comes to sound, it’s harder to be selective about what reaches your audiences. So having the right gear will make a big difference. (Don’t forget that you can rent this gear if you only have a few filming opportunities. If there are plenty, consider making the case for a forward-looking investment.)

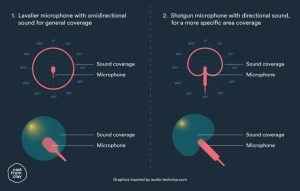

Microphones have a polar pattern. This describes how well the microphone picks up sound from different directions. Usually, they’ll be omnidirectional – picking up sound from every direction – or directional, which means they’re geared towards just one.

Imagine you’re interviewing one of your experts. You’ll want to minimise distractions. The polar pattern of a lavalier microphone helps you because it’s omnidirectional, and it will pick up sound whatever way it ends up pointing. Your expert shows up for the interview, and you’ll pin a lavalier microphone to their clothing. You can check the connection to your audio recorder, hit record, and focus on filming.

Now, imagine that we need to shoot in a more dynamic environment, like an event. It’ll be less easy to set up the straightforward filming situation we’ve just described. In that context, you might choose a shotgun microphone, which is highly directional – it’s designed to reduce sound coming from the front and sides. You can focus on capturing video, while a colleague with a directional microphone holds the microphone at a distance, out of shot.

There’s another advantage to thinking carefully about your audio, and making sure you record it well. You can use this audio to create other communications products – from podcasts to audio clips for social media. You can also fall back on the audio to serve your communications objectives if something unforeseen happens to your video setup.

Start simple and add interest

Interviews offer the most straightforward way to tell stories. And that’s a good thing because interviews allow you to shoot video in a controlled environment. You can think through where you want to set up your camera: to draw your viewer’s eye to the subject and add visual interest without distracting them. You can make choices about lighting and sound in advance, and get everything ready for when your interviewee arrives.

In policy communications, this is likely to be what you’ll shoot the most. That’s because keeping things simple helps you focus on what’s most important – capturing a credible spokesperson telling a compelling story.

But it’s worth bearing in mind that our attention spans are context-dependent, and video demands complete focus. So for anything but the shortest and punchiest of videos, you’re going to need to think about what else you can add to your video when you edit it.

In early Hollywood, filmmakers shot one roll of film for the main action, and another to provide context and visual interest. As video producer Matt Eastland-Jones said, the A-roll tells the story, while the B-roll shows the story.

If you’re interviewing one of your experts, they’ll want to appear credible and trustworthy. You need to add some detail: perhaps it’s a close-up that captures their good character. We could show them working on the analysis they’re discussing. We could situate them in a place, with some footage of your organisation at work.

If it’s the event that counts, factor in some extra time to your shoot. Pick up your camera and point it at the details that would catch someone’s eye if they’d just arrived there.

B-roll is the “editor’s secret weapon”. When you’re sitting down to edit your footage, there will be moments when your attention begins to drift from the A-roll. Here, you’ll want to cut away to the B-roll you’ve collected, which adds both interest and important visual context.

You might also find there are places where the A-roll just doesn’t tell the story you need. Your expert digresses. Something distracting enters the frame. You need to cut to other footage, but that disrupts the visual continuity of your video. You’ll draw on your B-roll here, but it’s also the moment when good-quality sound repays your investment. It will maintain the continuity of your video when the picture changes.

Stories are essential in policy communications. Lately, we find that policy experts are already convinced that stories matter. Research communicators want to know how their organisations can tell more stories.

Video offers you a powerful way to do this, but don’t get put off by the equipment or the cost. With some good choices – and little or no investment – you can get started.