[This article was originally published on Simon Maxwell’s blog on 20 February 2020.]

A cross-cutting issue in a think-tank is one which involves several departments or teams. Historically, poverty and globalisation have been examples. ‘Africa’ has been another. ‘Europe’ is one we struggled with in my time at ODI, needing input on aid, trade, finance, and humanitarian action, among others. Climate change is a current example, and the inspiration for this piece. It goes without saying that climate change needs to be on everyone’s agenda – and that, given the complexity of the issue, people need to work together.

Cross-cutting issues are difficult to manage because they complicate management and create conflicting accountabilities. They are also often unfunded. The result can be that a leadership team decides on a cross-cutting issue, even identifies one of its number to be ‘in charge’, but then finds that people in the various teams are too busy with other projects, facing different incentives, or more accountable to their own team leaders than to the person responsible for the cross-cutting theme.

What can be done? This was the question I posed to young think-tank leaders at the WinterSchool for Thinktankers 2020, held in Geneva in February, and jointly sponsored by On Think Tanks, foraus and the The Think Tank Hub. We had already worked on a case study on linking research and policy in the field of climate change, and I then presented them with the following. It is the latest in a series of ‘pizza night’ cases: the first four (from 2018) deal with various aspects of think tank governance, the next (from 2019) deals with planning policy-relevant research (with climate change as an example). Observant readers will note that all the cases begin and end in the same way: the challenge is embedded in the body of the text.

Managing delivery

The office was closed and everyone had left, but in one corner of the building a light still burned. Cecilia wanted to go home to her family, it was pizza night, and she had hardly seen the children all week. But there was a Board meeting coming up, and as Director of the think tank, it was preying on her mind.

At the last Board meeting, Cecilia had presented her plan for a climate change task force, focused on the Glasgow COP in 2020. The Plan was exciting and forward-looking, and the Board had loved it. But now she was worried. Time was slipping past, and the ambition she had laid out was not being fulfilled. Her colleagues faced too many distractions, and too few incentives. The Board was worried, too. ‘Cecilia’, the Chair had said, ‘You are the manager as well as the leader. You need to think about the levers you can pull, and manage your way out of this’. Cecilia sighed. The Chair was right. She needed an action plan of her own to drive change internally. But was this a strategy problem, she wondered, or business planning, or budget, or HR? What were her levers, actually? And how could she use them?

Cecilia pulled off a page from her pad, and wrote a heading: ‘How to deliver the climate action plan’. She needed to fill that in, but it was too late to do more. She thought of the pizza and her mouth began to water. Margarita, she wondered? Or Quattro Staggioni? It was time to go home. Cecilia rose, stretched, and switched off the light.

It was interesting that the first response of the young think tank leaders, paraphrasing, was ‘well, just tell them to do it’. It’s an obvious answer, and sometimes it works. An anecdote: I once sat next to Paul Kagame, President of Rwanda, at a lunch in Davos, and asked him how he had brought about what many considered a difficult change, then in the news. ‘I just told them’, he said.

Not being either Paul Kagame, or a former General or President of any kind, I found myself telling the young leaders about Charles Handy’s wonderful book on Understanding Organisations, first published in 1976, a constant companion when I was teaching mid-career professionals at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS), Sussex in the 1980s and 1990s, and a useful resource in later roles.

If you want to change something, Handy said, think about your source of power and influence. Is it physical power, based on your size and strength? Is it resource power, based on your control of resources? Is it position power, in which ‘the manager is by right allowed to order people to do so-and-so’? Is it expert power, because you know best? Is it personal power, derived from charisma? Or is it negative power, the capacity to stop things happening?

Physical. Resource. Position. Expert. Personal. Negative. Which of these powers do think tank leaders have, and which are they prepared to use? Not physical, obviously; and not negative, given that the project is to get something done rather than stop something happening. Probably not expert, given that think tanks are stuffed full of experts. Probably not charisma either, given that think tank leaders are mostly researchers (that’s a joke against researchers, but it reminds me of the definition of an economist, which is ‘just like an accountant, but without the charisma’. Oh dear: I am both a researcher and an economist.).

The young thinktankers zeroed in on position power, but think tank leaders face difficult constraints, and position power is not always what it is cracked up to be. For example, fund-raising is often devolved to individuals or teams, which means that their first loyalty is to their external funders – well, anyway, it means that meeting contract deadlines is a higher priority than satisfying the latest whim of the leadership team. Further, creating cross-departmental work streams immediately imposes a kind of matrix structure on the organisation, with accountabilities running both vertically (to the team) and horizontally (to the cross-cutting theme). Matrix management is notoriously difficult, creating culture clashes, as Handy describes.

These are not problems limited to think tanks, by the way. I have written about the problem of cross-sectoral planning in the context of food security, drawing on experience from rural development, multi-sectoral nutrition planning, farming systems research, poverty planning, and industrial organisation. I also thought a lot at ODI (London) about role cultures and task cultures: people mostly wanted the problem-focused characteristics of the latter, but found themselves working in the more hierarchical structures of the former.

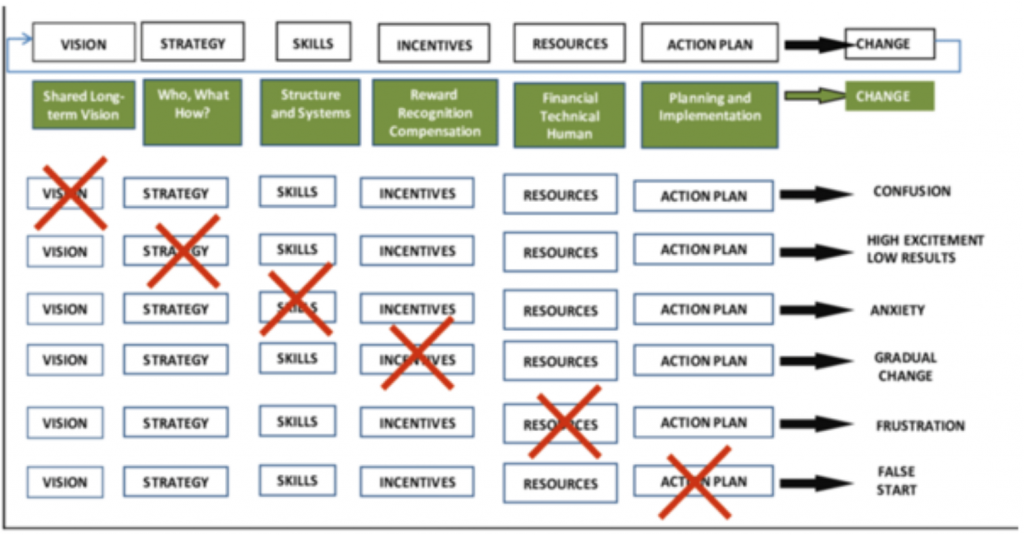

There’s a literature on delivering strategic change, of course. Duncan Green cited this diagram by Delores Ambrose in a recent blog (Figure 1), making the point that vision was of little use on its own, without strategy, skills, incentives, resources and an action plan. Personally, I find the Dorling Kindersley management handbooks a useful introduction to lots of topics. There is a Dorling Kindersley compendium called The Essential Manager’s Handbook, which provides useful advice. There is a separate little volume on Strategic Management, and another on Strategic Thinking: both deal with implementation challenges relevant here, like managing resistance to change, using targets and motivating people.

In the case of think-tanks, clues to the answer are given in the case study: strategy, business planning, budget, and HR are all involved. Charisma plays a role too. Some pointers:

First, ‘cross-cutting’ is not the same as ‘mainstreamed’. Mainstreaming is a frequent recourse for organisations trying to highlight a common issue: gender is a frequent case, difficult enough in its own terms, and often ineffective without a strong, practical management push. Cross-cutting implies something different, not just that the issue should be a priority across an organisation, but also that teams should collaborate. Ideally, there should be shared frameworks and analysis across the organisation; even, allowing for differences of opinion, a shared ‘narrative’.

Second, it definitely helps if the think tank director articulates a cross-cutting priority and is insistent. I remember Mike Faber, Director of IDS, Sussex in the mid-1980s, drawing our attention to the growing crisis in Africa, when structural adjustment became a big issue, and asking us to focus on the topic. No resources were available, but most of us adjusted our work programmes. That was when I began to work on food security in Africa. So a combination of charisma and position power had an effect.

Third, the cross-cutting theme needs to be visible in the five-year strategy, because it sends a signal and creates expectations, not least among the Board. A strategy document may also commit to creating an innovation fund, which can provide seed-funding for new cross-cutting themes.

Fourth, it is important to have the right person leading cross-cutting work. This should be someone senior enough to work across programmes and teams, probably a member of the senior leadership team; conceivably, for a major issue like climate change, the chief executive personally. Appointing someone too junior can mean that the issue disappears in management terms: for example, it may not appear with sufficient regularity on the agenda of senior management meetings.

Fifth, work on the cross-cutting theme should not just be driven top-down, but should also engender and build on energy from below. Creating a task force may be a good way to do this, with representatives of different teams. However, beware endless meetings and high transactions costs. An internal series of brown-bag lunches can be a good idea. In the case of climate change, internal change may also drive externally-focused research and policy work: develop an environmental plan, monitor and reduce flights, recycle, reduce bottled water, even (in one case with which I was associated) reduce or ban meat from the canteen.

Sixth, more detailed research and policy planning takes place in the context of the annual business plan. The structure of these varies, but it is usual to have chapters for both teams and cross-cutting themes, and for all of these to specify the big questions, the work streams and the expected outputs. Normally, also, the business plan will identify which staff will contribute to different activities. The plan never survives contact with reality, of course, especially if there is no funding, but again provides a template against which to assess progress. If an innovation fund has been created, then the business plan can be the point at which resources are committed.

Seventh, personal incentives need to be built into individual work plans, both for the cross-cutting theme leader and for individual researchers. Usually, a sketch of next year’s work programme is produced at the time of the annual appraisal. Does this include work on the cross-cutting theme? Are there specific outputs? Is it clear to the individual researcher that increments, bonuses and promotions are dependent on delivering for the cross-cutting theme as well as other work?

Eighth, management can help create opportunities to work with others on the cross-cutting theme. A model I have used is one of hubs and spokes: a wheel where each researcher pursues their own line of work, the individual spoke, but all come together at the hub from time to time, for joint projects. For example, there could be a shared series of public meetings, or a co-edited edition of a journal, a book even, or a briefing paper summarising the state of thinking on the cross-cutting theme. It is better, of course, if these are funded, and there may be scope to apply for new funding. However, cheap options need to be kept in mind: it costs very little, for example, to organise a series of public meetings. Joint activities need to be in the business plan. In all cases, working together helps to create a shared narrative.

Ninth, don’t forget to celebrate success – at the Board, in staff meetings, on the website, in annual reports, and in one-to-one encounters. Even better if the think tank’s work can be recognised as having produced real change.