[This article was originally published in the On Think Tanks 2018 Annual Review. ]

For many decades, think tanks have been able to carve out a neat place for themselves within the policymaking process, without having to seriously consider changing the way they undertake research or the way they fundamentally work.

That has now irrevocably changed. Policymakers and politicians are less and less likely to consider ideas unless those ideas can carry resonance with the wider audiences that they increasingly feel beholden to. They have even less time than they used to for thinking beyond the current election cycle. And they have less time to fully understand practical solutions, especially if those solutions don’t carry an emotional argument.

All of which means that think tanks no longer need to just rethink how they are communicating their ideas, but also how the research itself is conducted and how it can create more resonance with their audiences.

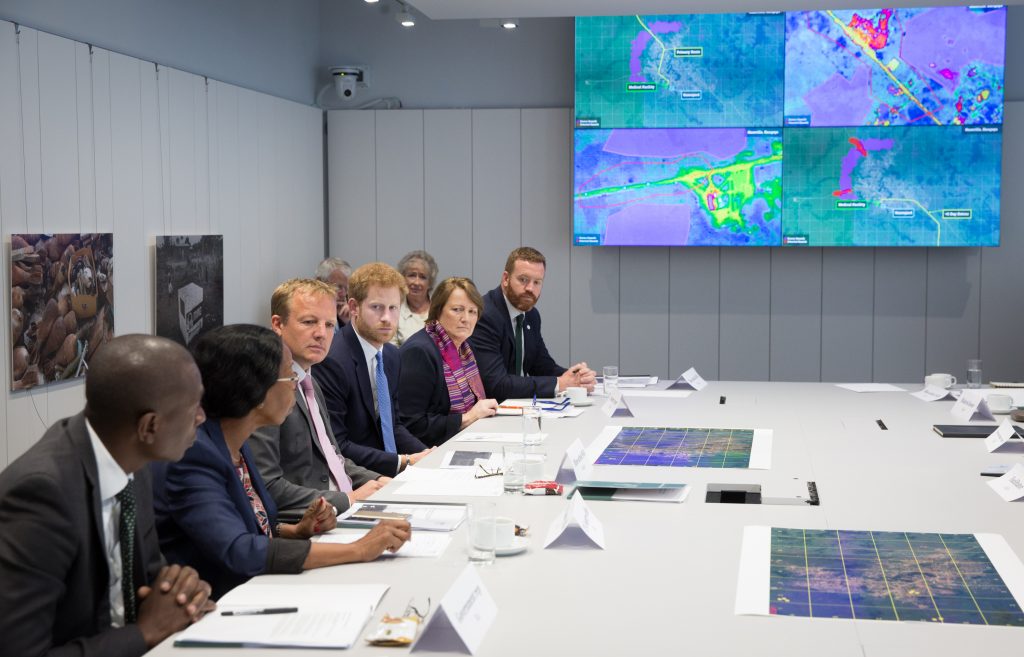

Increasingly Chatham House is using simulations and immersive scenario planning exercises to help us improve our research processes, stimulate dialogue and generate new ideas. Analysing, understanding and discussing problems is still vital but, alone, is not enough. Study groups, workshops and other meeting formats are now complemented by this ‘next step’ in events that engages people in different types of dialogue and where they are obliged to explore and tackle the process of making decisions in the face of rapidly changing and unexpected situations.

Our cyber simulations, for example, are designed to allow participants from the financial sector to be prepared and practiced in their responses to a major incident or crisis caused by a cyberattack. These simulations involve a series of crises and situations that evolve over the course of an afternoon or day, during which we stress-test responses and explore which courses of action are most valuable and which mitigating factors have the most impact.

Our researchers work with practitioners from the sector as well as policymakers, journalists and others to generate better ideas on cyber-related issues and thereby help us produce better analysis on the subject. Individuals often participate in role-playing or attend ‘as themselves’ representing their own organisations or fictional ones with given criteria for the exercise.

Technology underpins the situations, creating task-specific content such as social media accounts, emails and news reports to guide each scenario. These activities and processes are a long way from the first Chatham House report on cybersecurity, which was produced nearly fifteen years ago and came out of desk and other traditional methods of research.

In addition to cybersecurity, risk management preparedness is just one of the themes that can be explored in these exercises. Simulations on geopolitical or global strategic crises can explore state negotiations, stress-testing roles, responsibilities and outcomes. The common thread is an integrated high-tech space that can cater for a range of research, education and risk-management purposes.

The facilities, including a media studio, are also used for media training, multimedia content creation and scenario planning exercises, as well as more traditional roundtable discussions. For the communications department, the facilities have allowed us to create communications crises and job interview simulations. They have added a new dimension and energy to Chatham House’s programme of work and improved engagement with stakeholders.

Simulations and their related exercises are helping Chatham House and others make research and analysis more relevant to practitioners and policymakers. In turn, the outcomes should have more ‘real life’ implications for wider audiences – an important consideration today for every think tank.

Previous

Previous