Before defining the approaches they will employ to to being about research based policy influnce, think tanks need to ask themselves is: ‘what kind of organisation are we?’

According to recent work by ODI in Latin America –and drawing form the literature on think tanks- we could argue that think tanks can fulfil at least five roles (or services) in their political context:

- They can provide legitimacy to policies (whether it is ex-ante or ex-post).

- They can act as spaces for debate and deliberation –even as a sounding board for policymakers and opinion leaders. In some context they provide a safe house for intellectuals and their ideas.

- They can provide a financing channel for political parties and other policy interest groups.

- They attempt to influence the policy process.

- They are providers of cadres of experts and policymakers for political parties and governments.

How a think tank addresses these largely depends on how they work, their ideology vs. evidence credentials, and the context they operate in (including funding opportunities, the degree and type of competition they face, their staff, etc.).

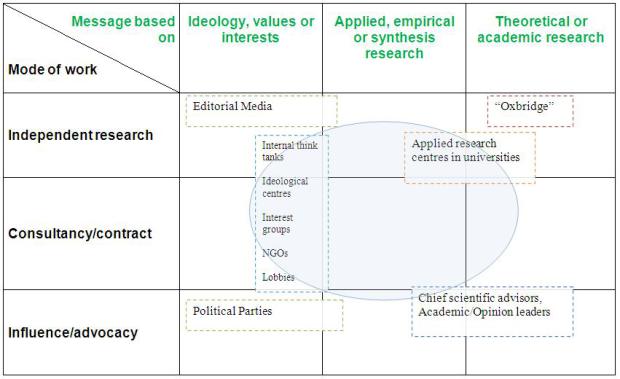

We ought to define where we stand in the policy-research inter-face. However, the common debate over whether an organisaiton is a think tank or a policy research centre or anything else is, really, unhelpful. We would struggle to define any of them. It is better (as in the Network Functions Approach) to describe what the organisation should do. Then the shape of the organisation should follow to allow this to happen. The following framework (based on Stephen Yeo’s description of think tanks’ mode of work) might help.

First, think tanks may work in or based their funding on one or more ways, including:

- Independent research: this would be work done with core or flexible funding that allows the researchers the liberty to choose their research questions and method. It may be long term and could focus on ‘big ideas’ with no direct policy relevance. On the other hand, it could focus on a key policy problem that requires a thorough research and action investment.

- Consultancy: this would be work done through commissions with specific clients and addressing one or two key questions. Consultancies often respond to an existing agenda.

- Influencing/advocacy: this would be work done through communications, capacity development, networking, campaigns, lobbying, etc. It is likely to be based on research based evidence emerging from independent research or consultancies.

Second, think tanks may base their work or arguments on:

- Ideology, values or interests

- Applied, empirical or synthesis research

- Theoretical or academic research

This is summarised in this matrix:

In the diagram above, independent theoretical research is the role of ‘Oxbridge’ type of research institutions. These are the ‘ivory tower’ research outfits (I do not think they are ivory towers, by the way) that focus on big ideas and little direct application or immediate relevance to policy. Some of these ivory towers, however, have Richard Dawkins (former Chair for the Public Understanding of Science at Cambridge University) type of actors who use their research to advocate for a particular issue or position.

Ideologically driven advocacy is the business of some campaigning NGOs, interest groups and lobbies. These do not always base their arguments or objectives on the nuances of research but rather they might use it to support ideologically or value-based defined positions.

Think tanks (or the organisations which play the role of think tanks) are more likely to exist somewhere in between the two –with links and clear separations between them.

Naturally, in the search for legitimacy, ideologically driven groups will seek links with think tanks and academic research centres; and think tanks will seek links with academic research centres; but not the other way around.

Think tanks may be successful at controlling the ‘value chain’ by presenting themselves as desirable and useful partners for both the academics and advocates. To academics, think tanks can only offer a clear link to policy and policy relevance (not high quality research); and through it to influence.

If a think tank moves too close to ideologically driven work it is likely to lose its independence. This could lead, however, to positive results as it might give it access to a political party or government administration and secure and stable partisan/private funding, etc. On the other hand, it might reduce its credibility and its policy space and funding opportunities.

If a think tank moves too close to theoretically driven work it might find itself competing in a market for which it may lack some key competencies and skills. Academic institutions are highly subsidised by their educational role and researchers have access o the necessary systems and resources for long term theoretical research that think tanks do not have. Furthermore, if think tanks are seen as competitors, academic researchers might be less inclined to collaborate with them.

One organisation cannot do it all.

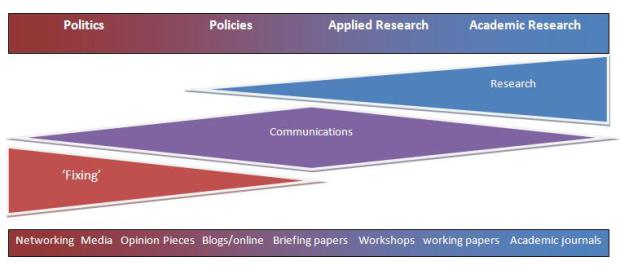

With this in mind it is possible to explore where and how the organisation might attempt to bring about change. A third dimension that may be added to the framework above describes the different spaces in which think tanks and other relevant actors might engage:

- The political space: among politicians and agenda setters driven by ideology and party concerns as much as evidence, moved by the demand of voters and public opinion.

- The practical or technocratic space: among policymakers, civil servants, analysis, experts, practitioners and policy entrepreneurs in the public sector, the media, in NGOs and in think tanks.

- The academic space: among researchers in university research centres, epistemic communities, academic journals and conference editorial boards, etc.

Fourth, there are three sets of skills that are relevant for those in the research-policy space:

- Research: academic in one extreme and analytical in another.

- Communications: including research communication, networking and media.

- Politics: including a thorough understanding of the political space, lobbying, etc.

To compete in one or another space, think tanks might have to trade-off some competencies or skills. For example, to succeed among academics, think tanks might have to trade-off their communication competencies (because of limited resources as well as pressures from more academic staff to focus on academic publications rather and policy engagement). And communications competencies (broadly defined) are what think tanks may offer academic researchers as a contribution to a productive partnership.

But, of course, deciding this depends on where the think tank decides to position itself:

These decisions, however, should be easier if the boundaries of the organisation are more clearly defined.

Previous

Previous