This is the presentation I gave at a recent meeting of think tanks hosted by ODI in London. It draws from other posts in this blog but, I hope, provides a stronger argument.

From: Rory Steward:

I do a lot of work with policymakers, but how much effect am I having? It’s like they’re coming in and saying to you, ‘I’m going to drive my car off a cliff. Should I or should I not wear a seatbelt?

And you say, ‘I don’t think you should drive your car off the cliff.’

And they say, ‘No, no, that bit’s already been decided—the question is whether to wear a seatbelt.’

And you say, ‘Well, you might as well wear a seatbelt.’ And then they say, ‘We’ve consulted with policy expert Rory Stewart and he says . .’

The common definition, employed by experts in the field like Diane Stone, James McGann and others, describes them as a distinctive class of organisations –not-for-profit and different and separate from universities, markets and the state- that seek to use research to influence policy. However, as I found in the study of think tanks in Latin America, Africa and Asia, these particular think tanks only exist in the imaginary of those who idealised the Brookings and Chatham Houses of this world; and more often than not, we find ourselves dealing with the exceptions rather than the rule -this was the point of my presentation on think tanks at an event in ODI in 2009: hybrids are the norm.

Tom Medvetz paper, Think Tanks as an emergent field, provides strong arguments against this view. He argues that this definition is limited because:

- It privileges U.S. and U.K. think tank traditions over all others;

- It leaves out many present day examples that do not fit with the definition: corporatist think tanks in Japan, public think tanks in Vietnam (RAND, by the way, is a federally funded organisation), university based think tanks across Latin America, partisan think tanks in Chile, Uruguay, the U.K. and the U.S., etc.;

- It robs the concept of think tanks of historical depth forgetting that the first think tanks were offshoots of the very same institutions they are now supposed to be independent of; and

- Most significantly, it fails to recognise the importance of the concept itself: He argues that the use of the label is a strategic choice made by organisations within a complex system of actors and relations.

This last point is worth exploring further. The sudden rise of funding for think tanks has seen a rise in the number of organisations positioning (or-rebranding) themselves as think tanks.

Medvetz explains how this positioning as a think tank involves a necessary ‘complex performance of distancing and affinity’:

- On the one hand think tanks assert their independence by differentiating themselves from universities, advocacy groups, public bodies and lobbyists; but

- On the other hand pursue strategies or behaviours that mimic their values and practices: appointing fellows, investing in communication departments and an array of advocacy tactics, pilot projects and policy proposals, and seek to actively influence and lobby policymakers.

The act of definition is then the art of forging the identity -independent or dependent- that best suits the organisation’s objectives; which, according to Medvetz’ analysis, is the accumulation of authority within the policy space. And in a multi-actor world, this is essentially a process that takes place in relation to others: we define Brookings in relation to the Heritage (U.S.), ODI in relation to IDS (U.K.), and CIUP to GRADE (Peru).

But also, And this is left out of his analysis, this definition takes place over time and is likely to change to fit the chaining context.

Another reason why the traditional definition of think tanks is flawed is that it does not offer us anything of practical value. What does one do with a definition that describes something as’something else’ or ‘not something else’? And what do we do when the one thing it says think tanks do is also what lots of other organisations do, too? How does a think tank use this definition to decide how to invest its resources, where to position itself, how to influence, etc?

To address this I attempt to describe think tanks according to their functions as well as to their position in the knowledge policy space. According to recent work by ODI in Latin America –and drawing form the literature on think tanks– we could argue that think tanks can fulfil at least six roles (or services) in their political context:

- They can provide legitimacy to policies (whether it is ex-ante or ex-post);

- They can act as spaces for debate and deliberation –even as a sounding board for policymakers and opinion leaders. In some context they provide a safe house for intellectuals and their ideas;

- They can provide a financing channel for political parties and other policy interest groups;

- They attempt to influence the policy process;

- They are providers of cadres of experts and policymakers for political parties and governments; and

- (I have added Hugh Gusterson suggestion of) An auditing function for think tanks.

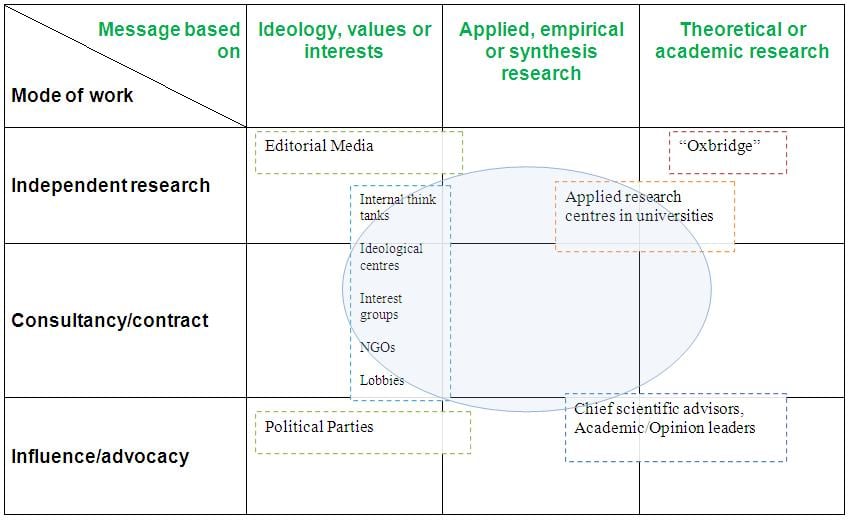

This approach to understanding think tanks opens the door to further analysis. The following framework (based on Stephen Yeo’s description of think tanks’ mode of work) might help.

First, think tanks may work in or based their business on one or more business models, including:

- Independent research: this would be work done with core or flexible funding that allows the researchers the liberty to choose their research questions and method. It may be long term and could focus on ‘big ideas’ with no direct policy relevance. On the other hand, it could focus on a key policy problem that requires a thorough research and action investment.

- Consultancy: this would be work done through commissions with specific clients and addressing one or two key questions. Consultancies often respond to an existing agenda.

- Influencing/advocacy: this would be work done through communications, capacity development, networking, campaigns, lobbying, etc. It is likely to be based on research based evidence emerging from independent research or consultancies.

Second, think tanks may base their work or arguments on:

- Ideology, values or interests

- Applied, empirical or synthesis research

- Theoretical or academic research

As described in this table showing the mode of work and basis of the messages, this kind of analysis is more likely to follow from a functional than the traditional definition.

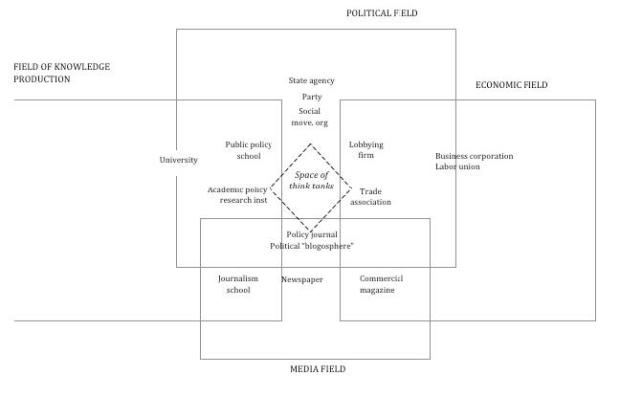

Tom Medvetz provides an alternative (and complementary?) framework for analysis that focuses on the positioning of think tanks within the social space:

With this in mind it is possible to explore where and how the organisation might attempt to bring about change (internal and external).

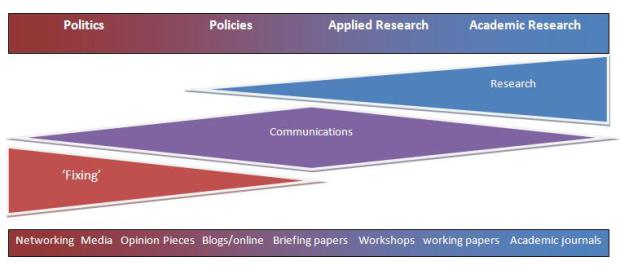

To compete in one or another space, think tanks might have to trade-off some competencies or skills. For example, to succeed among academics, think tanks might have to trade-off their communication competencies (because of limited resources as well as pressures from more academic staff to focus on academic publications rather and policy engagement). And communications competencies (broadly defined) are what think tanks may offer academic researchers as a contribution to a productive partnership.

But, of course, deciding this depends on where the think tank decides to position itself; and some think tanks may be closer to the media, politics or economic power.

These decisions, about the skills and competencies on which think tanks should invest, should be easier if the functional boundaries of the organisation are more clearly defined:

In the end (or as in the start of the presentation) everyone has an opinion about what is a think tank.

Previous

Previous