I have yet to be able to get through a presentation or debate about think tanks without the issue of their definition getting in the way of what would have otherwise been a thoroughly interesting discussion.

The common definition describes them as a distinctive class of organisations -different and separate from universities, markets and the state. This definition has been employed by experts in the field like Diane Stone, James McGann and others. However, as I found in the study of think tanks in Latin America, Africa and Asia, these think tanks only exist in the imaginary of those who idealised the Brookings and Chatham Houses of this world.

Tom Medvetz paper, Think Tanks as an emergent field, provides strong arguments against this view. He argues that this definition is limited because:

- It privileges U.S. and U.K. think tank traditions over all others;

- It robs the concept of think tanks of historical depth forgetting that the first think tanks were offshoots of the very same institutions they are now supposed to be independent of;

- It leaves out many present day examples that do not fit with the definition: corporatist think tanks in Japan, public think tanks in Vietnam (RAND, by the way, is a federally funded organisation), university based think tanks across Latin America, partisan think tanks in Chile, Uruguay, the U.K. and the U.S., etc.; and

- Most significantly, it fails to recognise the importance of the concept itself: He argues that the use of the label is a strategic choice made by organisations within a complex system of actors and relations.

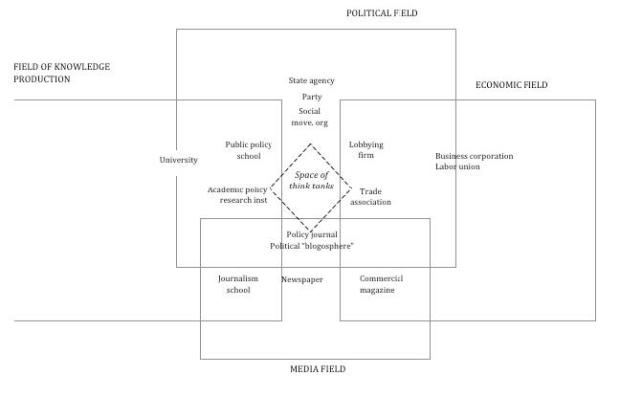

This last point is worth exploring further. I’ve attempted to describe think tanks according to their functions as well as to their position in the knowledge policy space. Medvetz takes this further to explain how the positioning of the think tank involves a necessary ‘complex performance of distancing and affinity’. He describes how, although think tanks assert their independence by differentiating themselves from universities, advocacy groups, public bodies and lobbyists, they simultaneously pursue strategies or behaviours that mimic their values and practices: appointing fellows, investing in communication departments and an array of advocacy tactics, pilot projects and policy proposals, and seek to actively influence and lobby policymakers.

The act of definition is then the art of forging the identity -independent or dependent- that best suits the think tank’s objectives; which, according to Medvetz’ analysis, is the accumulation of authority. And in a multi-actor world, this is essentially a process that takes place in relation to others: Brookings defines itself in relation to the Heritage (U.S.), ODI in relation to IDS (U.K.), and CIUP to GRADE (Peru).

I used to work in CIUP (a think tank linked to a Peruvian University). GRADE (an independent but consultancy-based think tank) was not so much a competitor as it was comparator. We defined ourselves as ‘not them’. And when I attempted to describe my work to my banker friends I used the image of a think tank more familiar to them, Apoyo, and then added a number of caveats (but in the university, focused on public policies, non for profit, etc.). Even now at ODI, barely a week goes by without a discussion about what IDS or CGD do differently.

So think tanks define themselves in relation to one another and in relation to the organisations that they want to be, depending on the circumstance, differentiated from or associated with (it could be the plot of any coming -of-age film: the son rebelling against the father only to realise he is just like the old man). In doing so they struggle to find their right position in what Medvetz described as the social space:

A definition then? I continue to find the definition of think tanks a futile endeavour (I am borrowing from Medvetz who borrowed from Simon James). Think tanks can be described by what they do (think tanks are like the bicycle chain that links the policy world with the research world, applying academic rigour to contemporary policy problems, maybe) and this should be understood within the boundaries of the context in which they exist and that account for their vast differences (more on this soon).

Previous

Previous