In a previous article,+ I reflected on how citizen voice and public engagement can increase the quality of research, as well as the credibility, relevance and perception of think tanks. In this follow-up article, I contend with how to operationalise this, providing an overview of some of the key things to think about, and the benefits and challenges of direct and indirect approaches.

1. Defining the purpose of your public engagement

For starters, a think tank will have to decide why it wants to engage the public, and to define the people that make up this ‘public’.

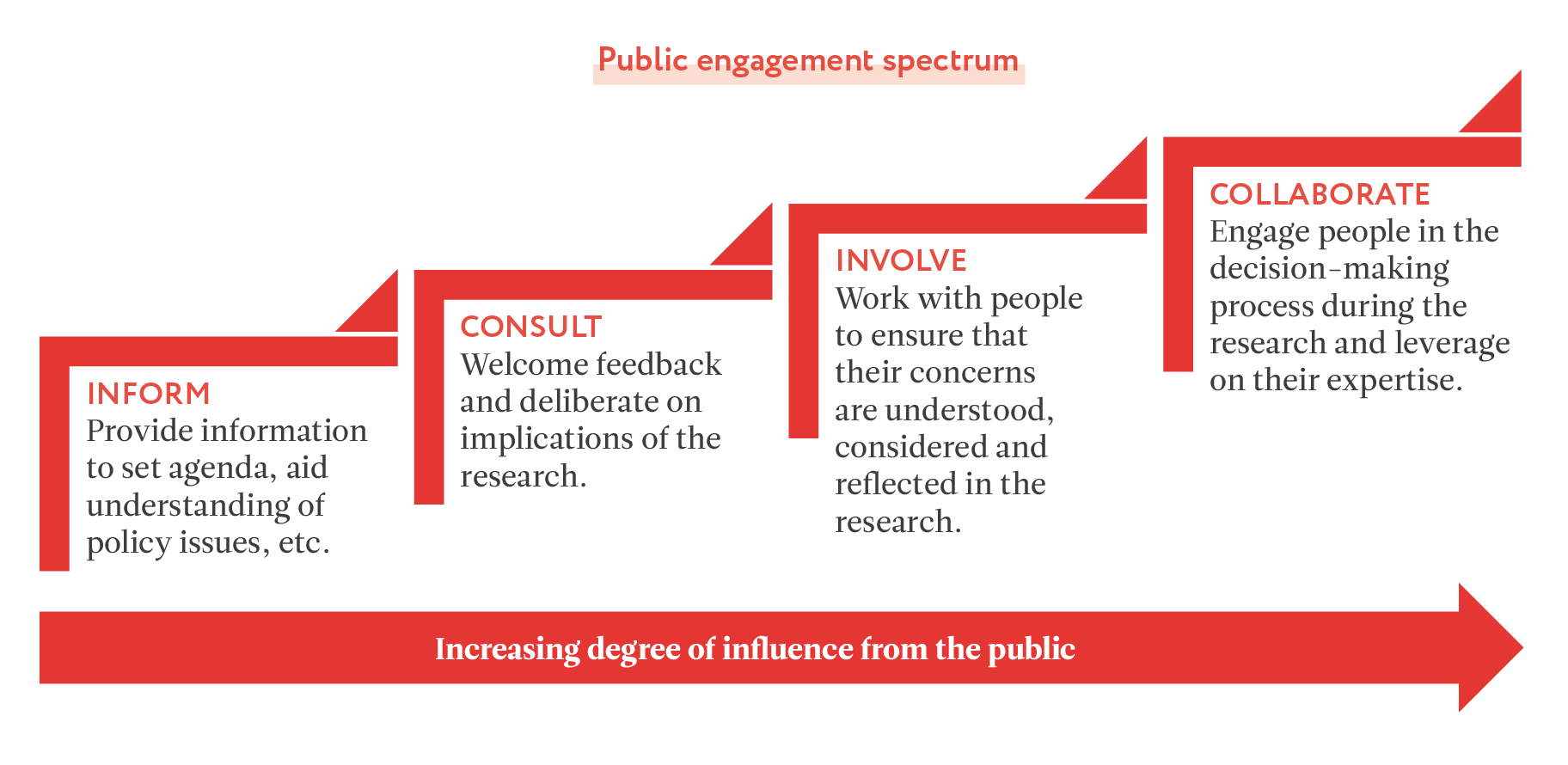

I think this spectrum is a helpful starting point to think through different levels of engagement, which will ultimately determine the choice of methods and tools:

2. Assessing the public’s willingness to engage

Before you engage with the public, it’s helpful to gauge their attitudes and willingness to participate, relative to the degree of engagement sought. How likely are they to want to support, or be interested in, the work of a think tank or research centre? This will inform the strategy and approaches for engagement.

For instance, a lot of people don’t actually know what a think tank is. A challenge with public engagement I have observed is that on first contact, some citizens perceive think tanks to be donors or NGOs.

There is an almost immediate change in attitude when you provide better clarity about the role of think tanks. However, a word of warning: in my experience in Nigeria, sometimes the public can be less enthusiastic or interested in engaging once you’ve explained that a think tank’s role is to support policymaking and practice, as this may feel removed from their day-to-day lives, whereas NGO and donor initiatives may deliver more immediate benefits or changes.

3. Methods for facilitating public engagement

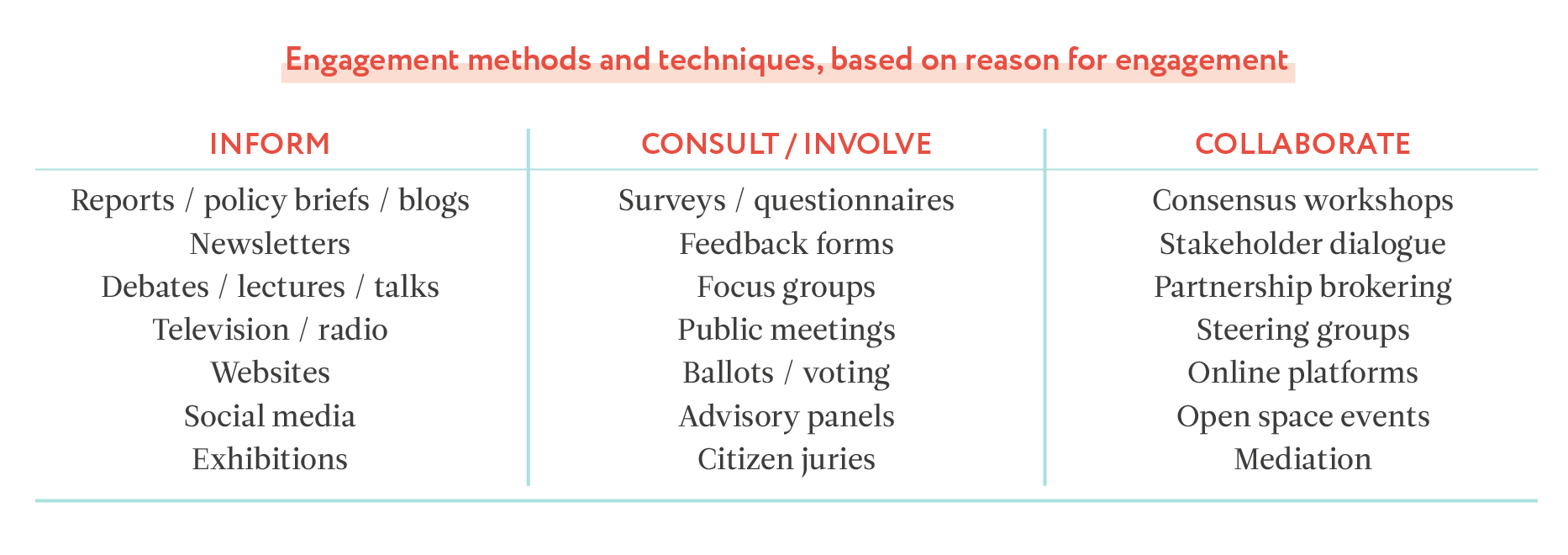

There are several methods and options available to think tanks to inform and engage the public in their work. This table highlights some of these ways:

4. Direct and indirect approaches for engagement

Methods for public engagement (beyond just providing information) can be divided into two main approaches: direct and indirect.

Direct approaches rely on the presence of the participating public in a shared space at a given time. An important characteristic of this approach is that the time and space for engagement is bounded and relatively short.

Direct engagement can be achieved through convening events, interviews or even virtual meetings. I described an example of a direct method of engagement in my previous article, whereby CSEA held a series of consultations and convened awareness workshops with education stakeholders.

Some of the benefits of direct engagement approaches include:

- contributions from the public are gathered quicker; and

- greater ability to structure and guide contributions from the public.

Indirect public engagement involves the harvesting of public input in a research process, facilitating contributions over a longer period of time. For instance, this could be facilitated through an online space or analogue suggestion box.

A good example of indirect public engagement is the foraus Policy Kitchen,+

which creates a space for informed and interested members of the public to collaborate and share ideas on issues of mutual interest. Decision-making web applications, such as Loomio, also facilitate indirect public engagement.

Some of the benefits of indirect engagement approaches include:

- longer time period allows for greater reflection and coherence of thoughts; and

- greater flexibility on timing.

Both approaches have their challenges, such as:

- balancing information overload on the one hand and struggling to generate interest and contributions on the other;

- potential trade-off between mass participation of non-experts and research output quality;

- ensuring that online platforms are secure against bot invitation, polarising agenda peddling, bullying or other risks of online participation;

- exclusion of people who do not have online access, or cannot attend physically; and

- moderating forums, aggregating comments and the political exercise of summarising/filtering some contributions and excluding others.

Previous

Previous