Top take-aways:

- Think tanks are well established in Australia and can exert some influence in a landscape that is quite open to contest ideas.

- There seems to be ample funding for think tanks and a high level of interest in where funding comes from.

- Australian think tanks are not known for their transparency. Many do not publicly disclose where their funding comes from, and there is currently a parliamentary enquiry into the contribution of government funding for public research on foreign policy.

Jump to:

- Overview of Australia’s think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Funding sources

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of Australia’s think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 64

- Average age of think tanks: 29 years

- Top three cities: Sydney (17 think tanks), Melbourne (17 think tanks) & Canberra (15 think tanks)

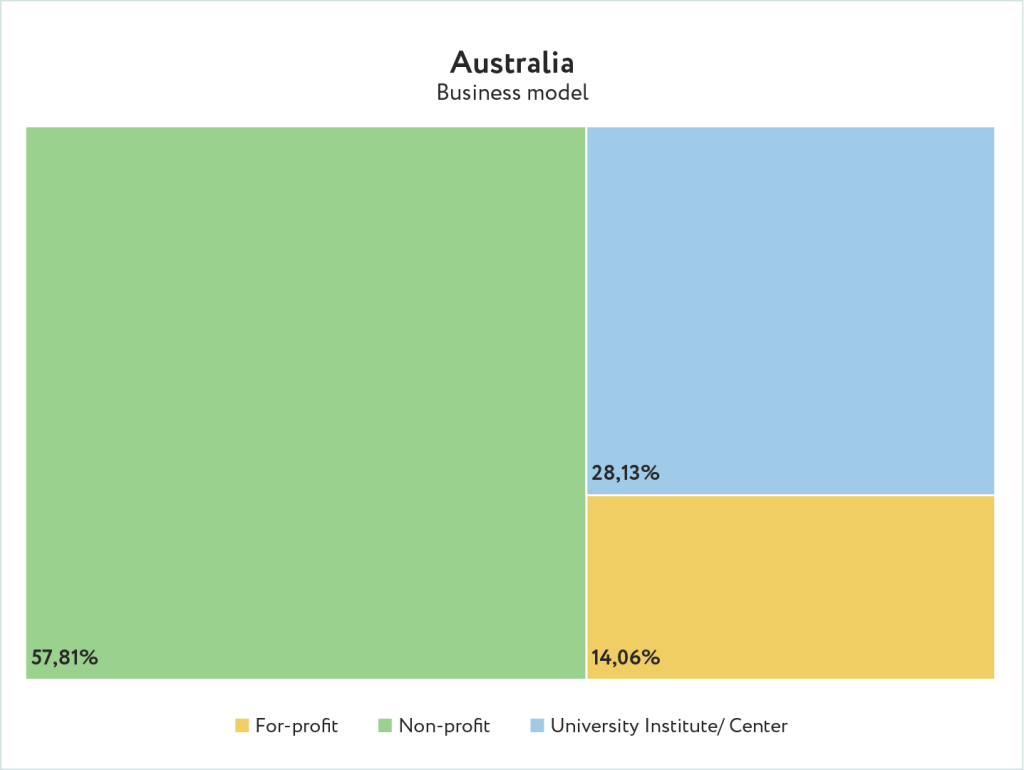

- Business models: Non-profit (57.81%), university institute/centre (28.12%) & for-profit (14.06%)

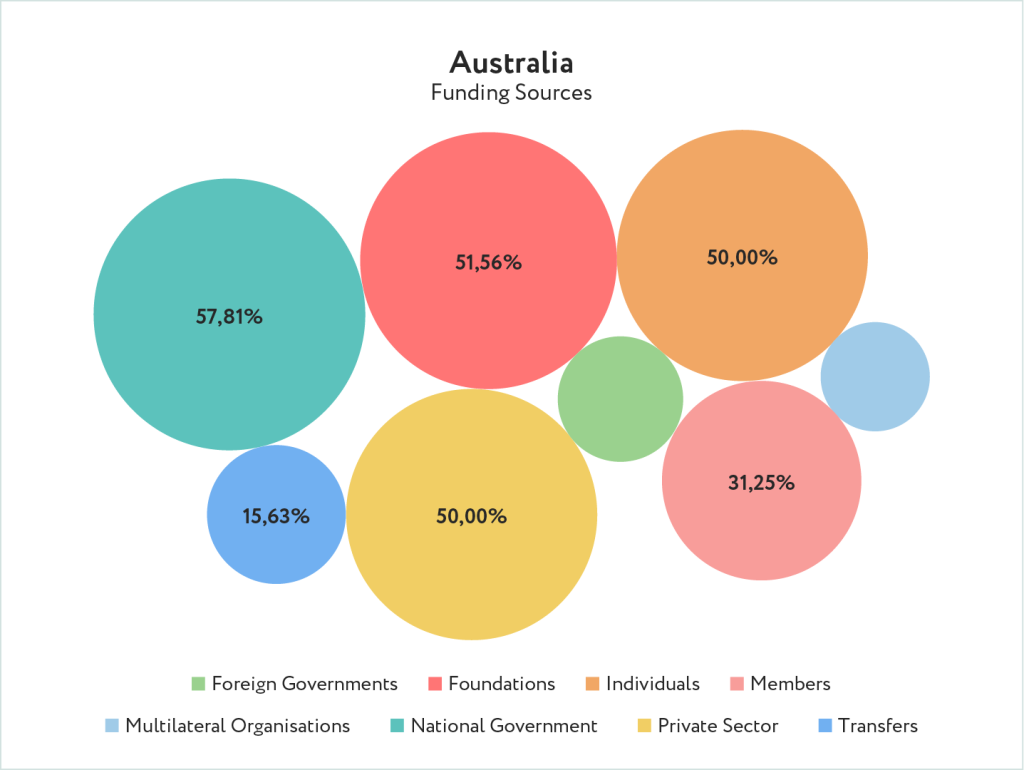

- Top three funding sources: National governments (57.81%), foundations (51.56%) & private sector (50%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in Australia were created between 2000 and 2009

- Staff size: About half of think tanks in Australia (40.62%) have up to 10 staff members

- Leader’s gender: Male (69.84% ), female (20.63%) & both (more than one person) (9.52%)

- Average % of female staff: 49%

Country context

The Australian landscape seems to be generally quite open to the contestation of ideas. There is an increasing proliferation of think tanks, and while they are not yet as embedded as those in the United States, they are well established and able to exert some influence in the policy landscape. They typically have good access to government and strong connections with relevant bureaucratic departments.

At the time of writing, Scott Morrison’s Liberal-National coalition is currently in power, although elections are upcoming in May 2022, and polling suggests there will be a change of government with the opposition Labour party set to take office. When it comes to international development the Liberal and Labour parties are somewhat aligned and foreign policy is not viewed as a partisan issue. The one exception to this is climate change, which is a highly divisive issue in Australia given the large rural population and mining sector.

Most think tanks in Australia tend to take similar ideological approaches to global issues and as such, there does not seem to be a major difference between left and right-leaning think tanks on these issues. There appears to be quite a bit of work being done on gender equality and gendered approaches to public policy, and economic recovery frequently comes up as an important theme.

Think tank characteristics

Australian think tanks influence debates, achieve media impact and often demonstrate a strong grasp of political timing, generating relevant research papers and opinion pieces as well as hosting lectures and advising policymakers. They tend to be much smaller than their US counterparts. There is some debate about how strong the ‘revolving door culture’ (i.e. movement between government and think tanks) actually is. However, there is some movement between think tanks and the government, and it is not typical for people to wait for the next administration before seeking a job, as tends to be seen in other countries.

The think tank world in Australia is a small network and everyone tends to know everyone. While networks of influence exist, they are small; as one respondent noted, this is because think tanks are typically small institutes and as such there is a small network of individuals working in these spaces. There were some influential individuals mentioned in conversations with think tank experts: one is Sharon Lewin at Doherty and another is Helen Evans, considered a very influential person who is engaged with Burnet and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, among others.

The majority of think tanks (57.81%) are set up as non-profits in Australia as seen in the diagram below. Although some think tanks have philanthropic connections. Approximately 28.13% of think tanks are hosted in universities, which includes groups such as the Doherty Institute at the University of Melbourne and the Australian National University’s Development Policy Institute, further details of which follow in Section 4. The two leading political parties also each have an official think tank. The Labour Party’s think tank is the Chifley Research Centre and the Liberal Party has the Menzies Research Centre, which is a Conservative public policy centre. Both are well thought of, but are, of course, not independent.

Funding sources

Compared to other western democracies there is more funding for think tanks in Australia than exists elsewhere.

While some think tanks such as the Lowy Institute and the Grattan Institute are transparent about their funding sources, many Australian think tanks tend to be somewhat opaque and provide minimal or no information about who funds their policy research and advocacy. Many think tanks, including the Institute of Public Affairs and the Centre for Independent Studies, do not publicly disclose information about donors.

This lack of funding transparency can create murkiness in terms of the agendas that think tanks pursue and the potential links they have with donors. The following visual illustrates the diversity of funding sources based on Open Think Tank Directory data.

There is currently a parliamentary enquiry into the contribution of government funding towards public research on foreign policy, and submissions are being received from think tanks and universities. This inquiry is looking at current funding by Australian government departments and agencies, the quality and diversity of publicly funded think tanks focused on foreign policy, ways of enhancing greater public understanding of foreign policy issues, and strategies the Australian government should adopt to build the knowledge needed to support more effective future foreign policy.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Think tanks in Australia appear to be influential in public and policy debate. They regularly participate in debates, are sought out by the media, generate relevant papers, host lectures, and advise policymakers. One respondent noted, however, that there does not seem to be a strong sense of whether or not the Australian government draws on the work of think tanks. While think tanks can clearly contribute to the policy debate, their work does not necessarily influence policy making or policy change; instead, policymakers are more reactive to media and public opinion.