Top take-aways:

- The French policy research ecosystem is mainly publicly funded as the country’s political and administrative culture has shaped administrative bodies to provide advice and expert opinion to decision-makers.

- Think tanks in France are centralised around the government in Paris. Independent think tanks exercise limited influence due to the French administration’s endogamy and policy-making oligopoly.

- The two main think tank types in France are politically orientated – typically with direct access to political actors -,and academically orientated – with little policy influence.

- Think tanks in France are increasingly renowned and trusted by citizens and public authorities withaccess to parliamentarians, ministers and cabinet secretariats.

- French president Emmanuel Macron has strong connections with the centre-left think tank Terra Nova and there is widespread perception that his decisions are informed by think tanks. This has been an emerging trend observed in the past two French administrations.

Jump to:

- Overview of France’s think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of France’s think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 101

- Average age of think tanks: 24 years

- Top three cities: Paris (82 think tanks), Aix-en-Provence, Marseille & Nogent-sur-Marne ( 2 think tanks each)

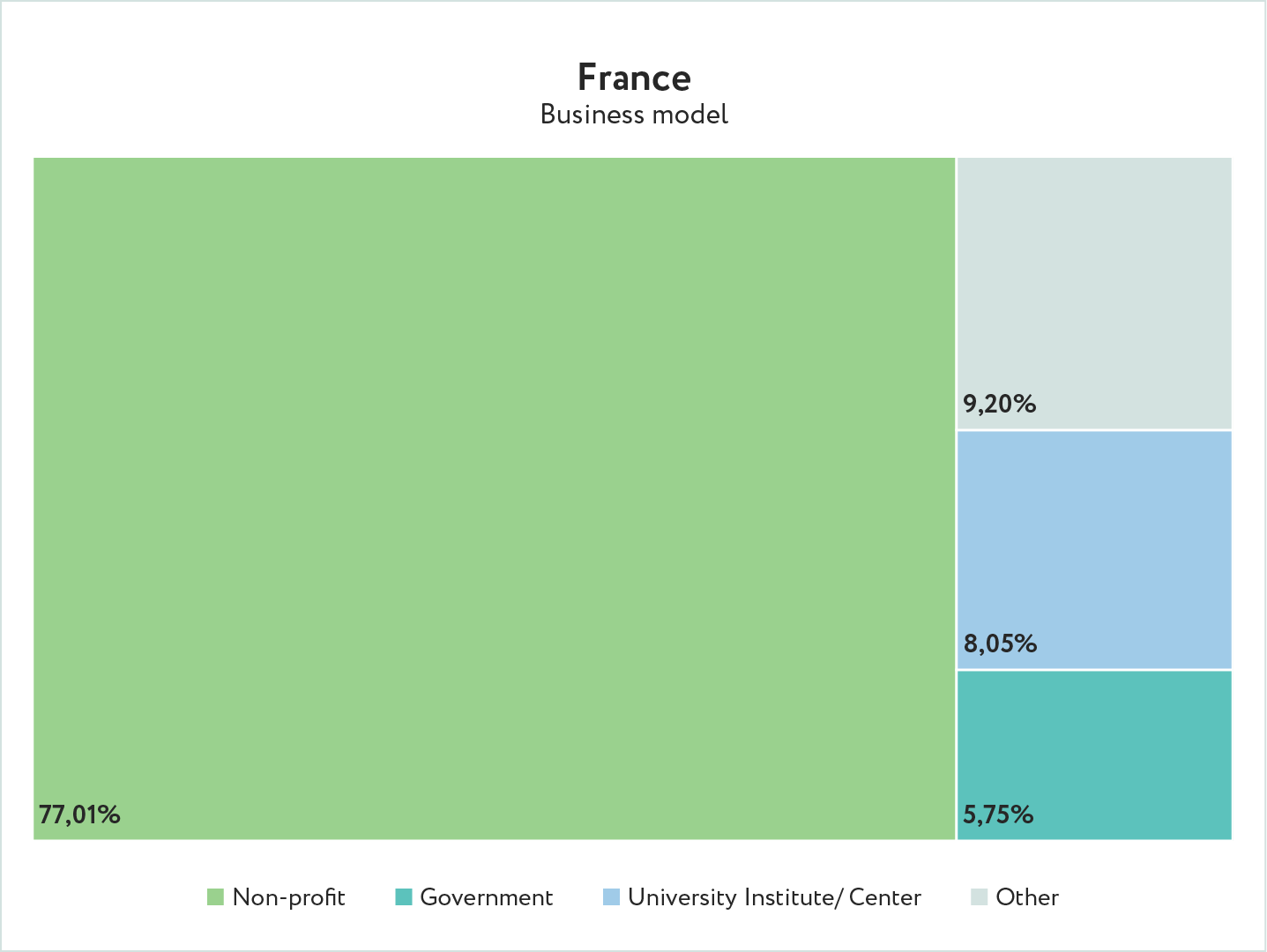

- Business models: Non-profit (66.33%), university institute/centre (6.93%) & government (4.95%)

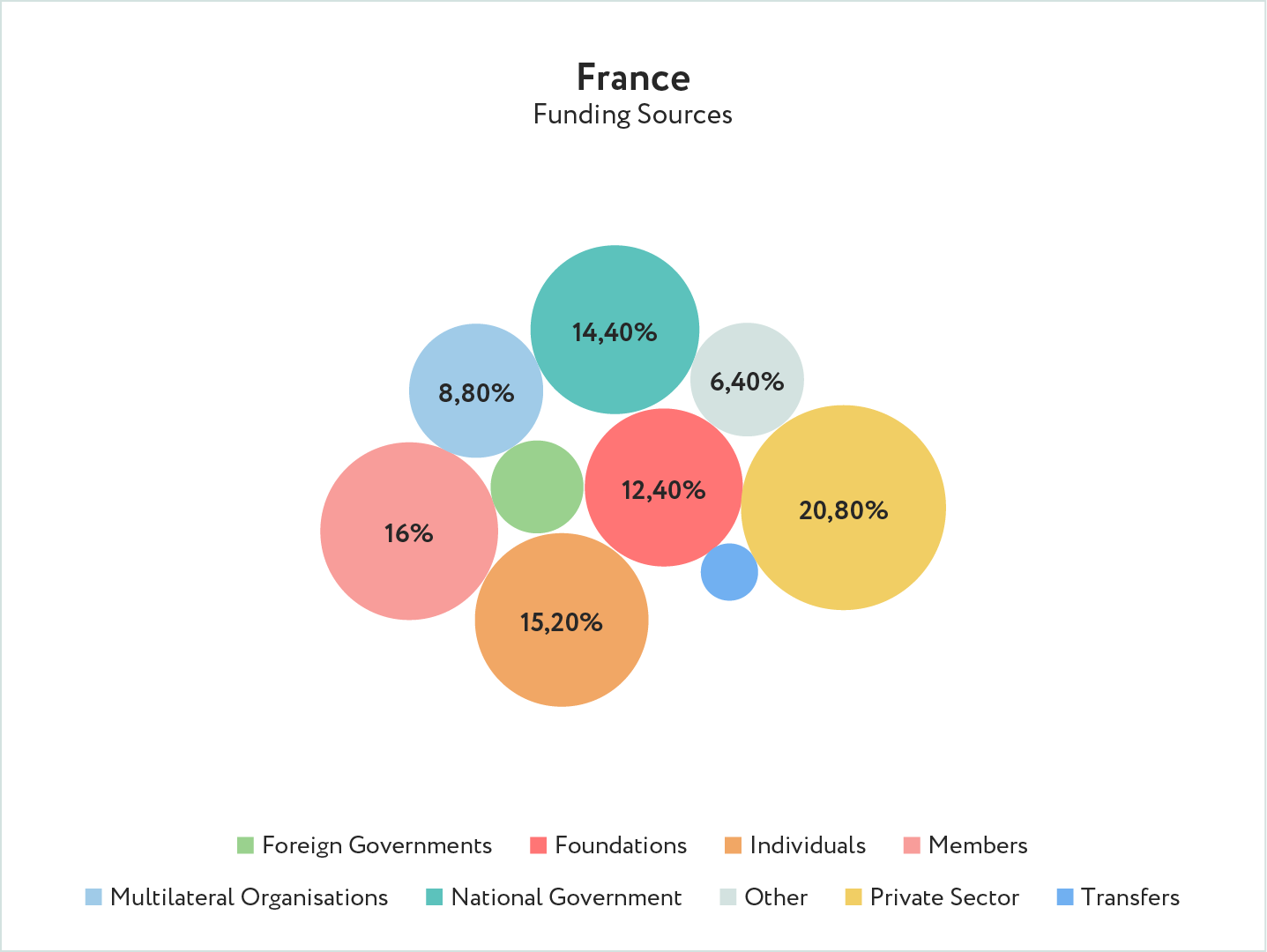

- Top three funding sources: Private sector (51.48%), members (39.60%) & individuals (37.60%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in France were created between 2000 and 2009

- Staff size: 32% of think tanks in France have up to 10 staff members.

- Leader’s gender: Male (72.94% ), female (20%) & both male and female (more than one person) (7.05%)

- Average % of female staff: 44%

Country context

The French policy research ecosystem is mainly public and, like in Japan, subject to significant oversight from its central administration. France’s political and administrative culture has shaped public bodies to provide advice and expert opinion to decision-makers.

With a historical tradition of clubs and salons, prominent French intellectual and political figures like Thierry de Montbrial + and Pierre Joxe participated actively in the creation and subsequent development of several think tanks in the 1970s (Institut Français des Relations Internationales, 1979 and the Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, 1992), based on the UK/US experience.

French think tanks started to become more structured in the early 1990s and the early 2000s were marked by a strong consolidation of think tanks, particularly since the presidential elections in 2012. This is when most think tanks in France benefited from significant media coverage that contributed to their institutionalisation.

Since 2010, thihk tanks have been increasingly publishing academic papers, parliamentary and ministerial reports, and have become a key point of reference for policymakers. The creation of the Observatoire Européen des Think Tanks in Paris (OETT, 2006) further contributed to the establishment and standardisation of the think tank phenomenon in the country, with annual recognitions and rankings.

Nevertheless France, unlike Germany, has not yet been able to foster the creation of a large think tank ecosystem promoting the generation of new ideas. The reasons for this are numerous and intertwined. The French administration’s endogamy, its universities focus on pure academic research and the difficulties of private and public actors working together are some of the key drivers. In France there is a general level of mistrust of anything political with Anglo-Saxon characteristics and this has led to advocacy groups and think tanks being largely rejected by the public, with think tank funders retrenching from France.

French citizens are very sceptical about the idea of a revolving door culture and in general this is not a common phenomenon. Two exceptions to this were the presidential advisors of former president Francois Hollande and current president Macron, who is reported to be close to the left-wing think tank Terra Nova. President Emmanuel Macron brought in several advisers from Terra Nova to his cabinet.

Think tank characteristics

France’s think tank model is radically different to the UK/US one as there are idiosyncratic factors that cannot be compared. In France there is a strong belief that there shouldn’t be intermediaries between the private and public interest, as some private interests might get in the way or even go against the public interest. In general, the nature of think tanks as research bodies relevant to policymaking is clearly distinct from that of political clubs and professional circles. This distinction is less clear in France, however, where in practice “formal” institutions and “informal” organisations or clubs, regardless of their size, tend to be diluted. +

Like in Spain, think tanks in France remain relatively unknown to the public. Though most think tanks in France are mainly established under the form of public utility non-profits as foundations and non-profits, the lack of a common framework and legal status contributes to the difficulty of understanding the French think tank ecosystem.

Compared to public institutions, research institutes hosted by universities and political sciences schools such as Sciences Po Paris, think tanks have lower media visibility and public exposure. Research university institutions like the Centre d’études et de recherches sur le développement international (CERDI) are generally academically orientated.

They tend to lack a communications plan to strategise and influence the policymaking process by making sure they publish ideas at “the right time” and do not dedicate resources to networking or engaging actively with the public administration. The following graph illustrates the business models of French think tanks.

France has two main categories of think tanks: politically orientated think tanks and academically orientated think tanks.

Politically orientated think tanks tend to be led by high-level people with direct access to policymakers. On one hand are those that have transpartisan or political linkages such as the Institut Montaigne (centre-right) and Terra Nova (centre left), and on the other hand there are politically affiliated thinks such as the Fondation Jean Jeaurès (French Socialist Party) or the Fondation Gabriel Péri (Communist Party) who deliver ideas on many topics but tend not to specialise in specific themes. Despite the rise of political foundations, the French model remains distinct from that of Germany, as there are no financial links between the foundations and political parties.

The second dominant category of think tanks is that of the academic and research-orientated think tanks, which are independent from political affiliations. Some examples are the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI) and La Fabrique Écologique. These think tanks are reported to offer different ideas on domestic topics such as the reform of the retirement system or the question of gas dependence versus renewables, but are not specifically policy orientated, nor do they aim to influence the policymaking process.

Think tanks that do not fall within these two dominant categories are those with specific expertise in international relations and European affairs that have been established to respond to the Europeanisation process. The Fondation Robert Schuman and the Institut Jacques Delors-Notre Europe were specifically conceived to promote European Union integration from inside and outside the country (mainly Brussels). The Institut Français de Relations Internationales (IFRI) is the think tank pioneer, internationally recognised as the leading French think tank. Both the IFRI and l’Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques (IRIS) are specialists in foreign policy and are regularly invited for interviews by media outlets. These are two of the most visible and highly rated in international think tanks rankings.

Public funding (both domestic and EU) has expanded in France with many think tanks relying on these sources more today than in the past. Only a few like the Institut Montaigne, backed by the AXA Group, do not rely on public funds or financial aid from the French state. In general, the think tank landscape in France is poorly structured and, with little private and public funding, suffers from scarce financial means. The think tanks focused on foreign affairs and defence (i.e. IRIS, IFRI) are the ones that most resemble the US model: a research structure with permanent contracts, a variety of publications, distinguished journals, mixed budgets (public/private) and political neutrality.

In France, there are six principal sources of think tank funding: the state, territorial authorities, European funding, individual donors, foundations and, increasingly, private companies. The following visual illustrates the diversity in funding sources of think tanks in France. The Other (6.4%) bubble likely includes EU funding.

Compared to the US model, foundations play a minimal role in Europe. One of the main sources of public funding is the French prime minister’s office “Matignon”. For that reason there is active lobbying among think tanks, as Matignon offers a discretionary part of its budget to all French associations with very little transparency, regardless of their activities and sectors. A broad variety of think tanks are reported to have benefitted from this funding source: the Fondation pour l’Innovation Politique (Fondapol), the Fondation Gabrielle Péri, the Fondation Jean Jaurès and the Fondation Robert Schuman. This makes the French system a clientelistic one, where the representation of interests is what matters and where think tanks are at risk of becoming politicised.

Public think tank France Stratégie is very close to the French public administration and is hosted by the prime minister, but with its own autonomy. This public think tank gives public policy recommendations and works with private and independent think tanks by providing them with yearly funding in smaller amounts. Line ministries such as the Ministry of Defence host in-house think tanks like Direction Générale des Relations Internationales et de la Stratégie (DGRIS), which are at the centre of the army and help orientate France’s foreign policy and defence strategy. The Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Environment also give smaller amounts to a selected number of think tanks like I4CE and Agreenium, the French Institute of Agronomy, Veterinary and Forestry, to fund research in the agriculture field.

The rest of the financing comes from European public funding (European Commission) under Horizon Europe (former Horizon 2020) and Europe for citizens grant schemes. Think tanks like the Institut Jacques Delors, the IRIF, the Fondation Schuman and the IFRI have been significant recipients of EU funding. Foreign governments like Russia, the USA and Turkey also fund think tanks through their embassies. This is the case for IFRI and Fondapol.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

French political culture has remained state-centric and primarily structured by political parties. The “French model”, whereby the state has its bodies of expertise and control, radically differs from the UK/US model based on the principle of “advocacy”.+ Given the policymaking oligopoly and that think tanks are not immune to a degree of suspicion towards expertise, there is much less appetite for think tanks in France than in the United States. Interviewees report these perceptions to be slowly changing. However, the French state and its public administration remain the primary source for policymaking and still tend to consider themselves omniscient on public issues.

Regardless of these constraints, think tanks are increasingly becoming renowned and trusted by citizens and public authorities in France. According to a consultation by the Think Institute, 48% of French managers and executives perceive French president Emmanuel Macron as being influenced by policy ideas and recommendations put forward by some think tanks.

Think tank demands from public authorities, companies, the media and academia continue to intensify and diversify. For instance, the government’s demands and expectations concerning think tanks specialising in foreign policy and international issues are reported to be “extremely ambivalent”. On one hand, the state does not generally involve think tanks when developing its foreign policy for instance, while on the other hand think tanks are asked to serve the national interest while maintaining their independence. +

An example of this instrumentalisation is the relationship between the IFRI and its stakeholders, which is fundamentally a relationship of influence. The IFRI aims to work for the benefit of the public interest, hence it exercises its influence both in France and abroad to drive public debate on major global issues.

Both the IFRI and the IRIS have earned their good reputation and credibility through their expertise on geopolitics, defence and security. They are among the think tanks with more decisive influence in their field both in France and in the world, have pretty good exposure in the media and they plan their studies as an aid to decision-making (whether public or private).

Other think tanks such as the Institut Montaigne and Terra Nova have a stronger voice in domestic policies, though they have also become increasingly relevant in the foreign-policy field. These two political think tanks have high-level leaders with direct access to the policymakers and are reported to have the most access to the “Élysée”, the presidential office.

In terms of interactions with public authorities, think tanks like the IFRI are reported to take part in the power competition by seeking public notoriety at the expense of those with other partners, particularly companies, both as vectors and as targets of soft power. In this sense, there is some debate about whether these type of think tanks should represent French voices in the debate of ideas or France’s voice with foreign countries’ decision-makers. + Think tanks play a key role in helping build political narratives but are also forgotten by many policymakers who do not understand their added value.

In this sense, compared to Germany, the French think tank ecosystem faces the challenge of justifying its added value. This is changing, with some think tanks, such as I4CE, reporting no longer having any trouble arranging meetings with high-level parliamentarians, ministers or cabinet secretariats. However, the interviewee who related this emphasised that building “this relationship took years”.

Interviews reported that credibility with the French finance ministry is granted to well-known economists working on macroeconomics issues for many decades and former advisors to the finance ministers or the French Treasury, such as Jean Pisani-Ferry, who is now the current chairman of I4CE, a pro-climate think tank. Interviewees also perceive the Institut Montaigne and Terra Nova as close to the finance ministry.

Previous

Previous