Top take-aways:

- The German think tank ecosystem is relatively small compared to those of the US and UK, but amongst the largest and most diverse in continental Europe.

- While most of Germany’s think tanks maintain political independence and seek to avoid being tied to the political right or left on a particular ideology, there is a dominant group of political party foundations, such as the Konrad-Adenauer Foundation, which is linked to the Christian Democratic Union (centre-right), and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, which is close to the Social Democratic Party (centre-left).

- When advice is needed to fill knowledge gaps, the government calls on competent and credible think tanks that they already trust to brief them on new subjects of interest, such as digitalisation and energy.

- The German Institute for International and Security Affairs is the most influential think tank to the political elite because its explicit task is to advise the government and parliament on foreign policy matters, while the German Council on Foreign Relations is the most influential towards public opinion.

Jump to:

- Overview of Germany think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tank characteristics

- Funding sources

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of Germany think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 185

- Average age of think tanks: 35 years

- Top three cities: Berlin (59 think tanks), Bonn (16 think tanks) & Hamburg (11 think tanks)

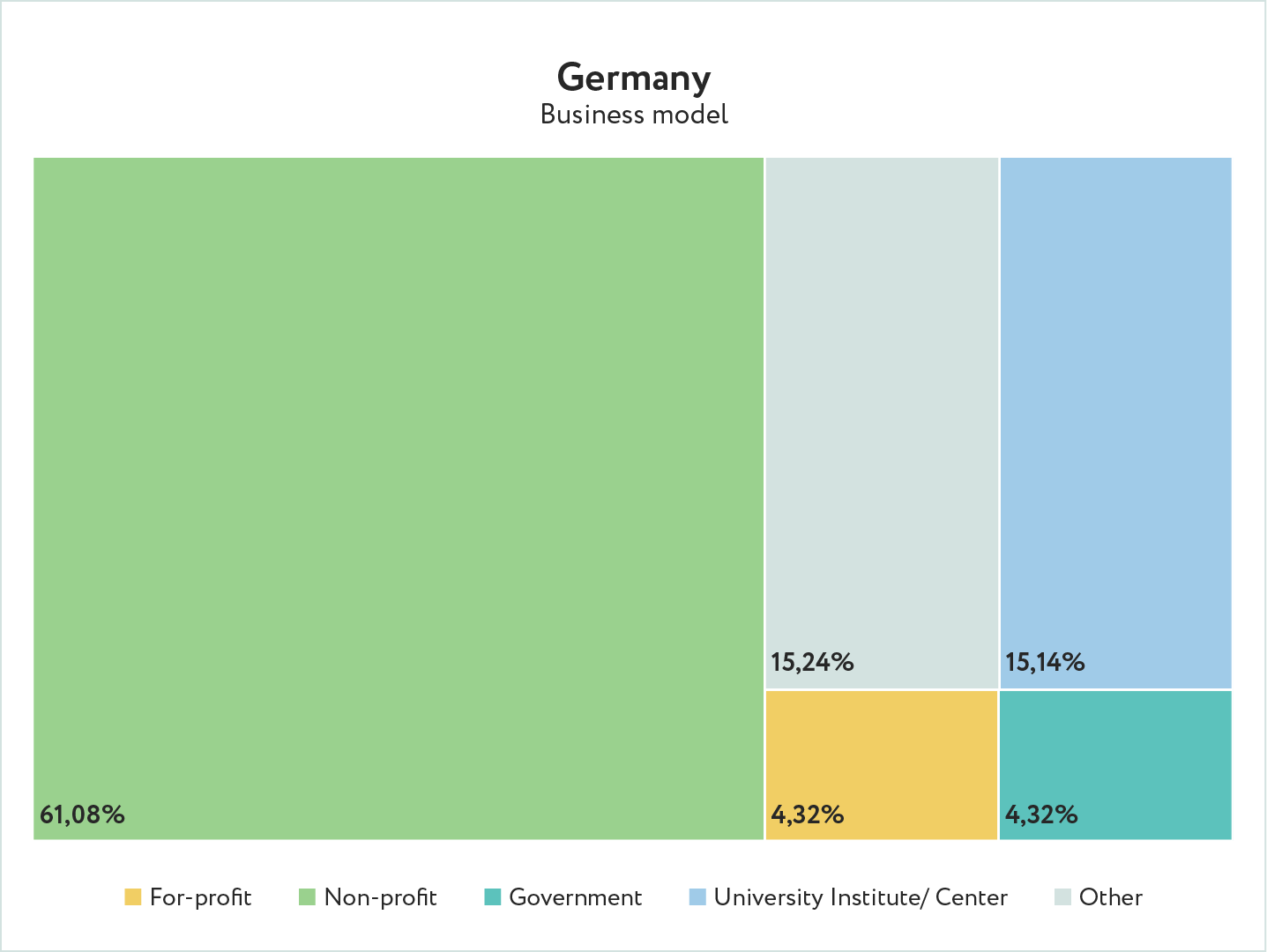

- Business models: Non-profit (61.08%), other (15.14%), university institute/centre (15.14%), for-profit (4.32%) & government-affiliated (4.32%)

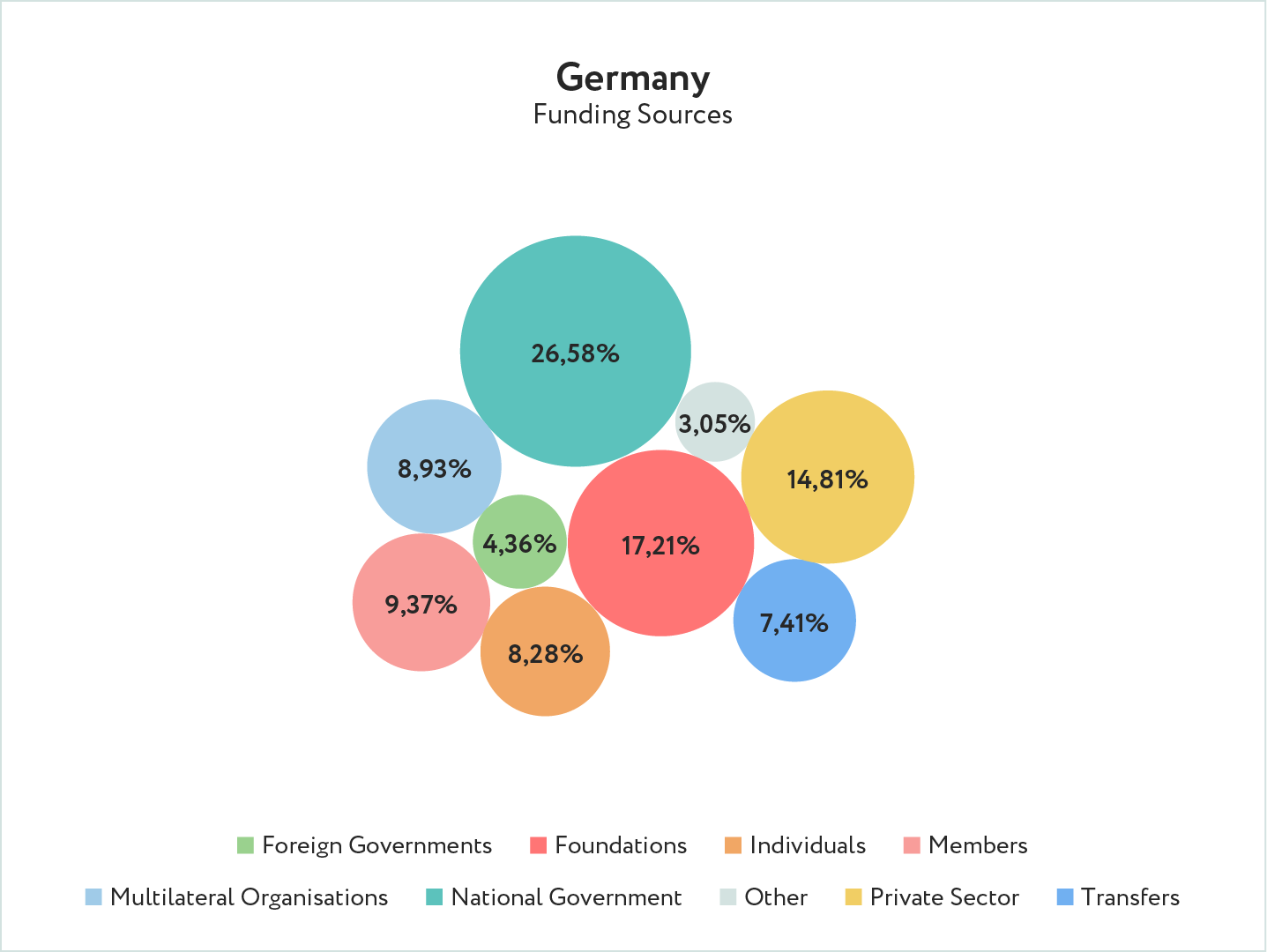

- Top three funding sources: National government (26.58%), foundations (17.21%) & private sector (14.81%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in Germany were founded between in the decade between 1989 and 1999

- Staff side: Almost half of think tanks in Germany (44.44%) have more than 46 staff members

- Gender of leader: Male (69.10%), female (21.82%), both male and female (organisations led by more than one person) (8.48%)

- Average % of female staff: 49%

Country context

The German think tank landscape has been growing and becoming increasingly diverse, with new think tanks being established and international ones setting up satellite offices in Germany. As the landscape becomes more complex and nuanced, the opportunity for this community to provide an effective platform for intellectual capital and policy advice continues to take shape.

In general, the term ‘think tank’ is perceived by many in Germany as having a negative connotation, has not been well-defined, and is not well understood by most German citizens. Germans’ impression of think tanks often overlaps with their perception of NGOs, universities, foundations, and so on.

In terms of the national government’s domestic and global policy priorities, foreign policy, defence and security, together with climate and energy, top the list. Think tank research agendas are well aligned with these government policy priorities.

Despite this alignment, think tanks have been criticised for not acting fast and strategically enough to take advantage of the window of opportunity when political advice is needed. This adds to the perception that they are “too academic”, that they lack innovation and avoid taking the risk to ask new questions (see Mercartor study).

The increased relevance of foreign policy in Germany is also reflected in the think tank landscape. The number of research institutions in the country that study foreign and security policy has exponentially grown, especially in Berlin. Many think tanks are focused on regional agendas including the Middle East/ North Africa region, and Asia, with a focus on China.

What is less prominent is a widespread subcontinental approach (e.g. Latin America and the Caribbean). Where there are pockets of subcontinental research agendas, they tend to be tied to specific sectors or to the priorities of special interest groups, and therefore lack plurality.

Think tank characteristics

The German think tank landscape is small compared with other national think tank communities such as those in the UK and the US, but it is probably the largest in continental Europe. The ecosystem is diverse as there are think tanks that take many forms(see table below): university institutes, political think tanks (including political foundations), private foundations, NGOs, do-tanks and activists. With a longstanding history of well-renowned academic institutions, many old, well-established universities house think tanks within the university structures. For example, the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, a private graduate school specialised in public policy and international affairs, has a reputation for strong policy research. Another such example is the Ifo Institute, a policy-oriented economic research facility and think tank linked to the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich.

Aside from the academically orientated think tanks, political parties will either have their own think tank or close relationships with a research centre that holds similar ideological views, on whom they rely for policy research. The Gunda Werner Institute, for example, is a research institution focusing on gender backed by the Heinrich Boell Foundation, the foundation affiliated to the German Green Party. Some of these political foundations are even creating strategic planning departments to compete with conventional think tanks.

In addition to the university institutes and political think tanks, there are business-orientated foundations (i.e. the Robert Bosch Foundation and Stiftung Mercator), NGOs (i.e. TMG – Think Tank for Sustainability), do-tanks (i.e. Polis180 and the Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy), and activists such as Gender CC – Women for Climate Justice that also act like think tanks and conduct thematic research. Beyond these more traditional sources of policy research, trade unions were also identified by interviewees as an important source of policy research.

Across the think tank spectrum, most think tanks maintain plurality and present research in a neutral, objective manner and avoid aligning with interest groups.

The natural exceptions are the political party think tanks who tend to be partisan and ideologically aligned. Initially founded to guarantee pluralistic political debate and civic education in Germany’s early democracy, these foundations remain some of the biggest players in forming public opinion and policy advice in Germany. Their activities range from political education and student funding to active support of determined government policies (mainly development policy).

Political foundations typically have a large number of staff with their own branch offices in both European and non-European countries where they promote democracy. Their work revolves around publishing reports on foreign policy issues from their own party political lens, this being the key characteristic that distinguishes them from the independent think tanks. Their target audience is primarily actors within their own political party and affiliated organisations, but their reports are also broadly read by other interested experts. The Konrad-Adenauer Foundation, linked to the CDU, and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, which is close to the Social Democratic Party of Germany, are the two largest of the politically affiliated research foundations in Germany.

The broader landscape is characterised by some gender diversity in entry to medium-level roles, but only 23% of think tanks are led by women. Some think tank staffers argue that this gender diversity is not reflected in other dimensions, such as socio-economic and cultural background or ethnicity, which is lagging in the German policy expert bubble. This creates the risk of a confirmation bias phenomenon. +

When it comes to the use of new technologies, German think tankers particularly differ from their Anglo-Saxon counterparts. The use of social media and infographics to communicate complex research results in an easily digestible way is an opportunity to tap into the German landscape. The majority of German think tankers have a political science background and thus their skills in quantitative data analysis and programming are often limited.

Funding sources

Given the current political context, with the rise of right-wing parties in European parliaments, there is greater scepticism in Germany about the independence of public-sector funding, putting issues of transparency and independence in the spotlight. +

German think tanks rely on public funding and the funding they receive from foundations. This does not imply that German think tanks are influenced by the government or the foundations, as independence of research is highly valued and tends to be respected by donors.

Funding from businesses and/or foundations could potentially influence think tanks’ research agenda if not well managed and openly communicated to stakeholders, but this has not been a particular problem in Germany. From a donor’s perspective, private sponsors generally prefer to fund projects as this gives them greater scope for control.

However, in Germany, new approaches that safeguard independence and combine aspects of institutional and project funding (i.e. long-term projects with a flexible budget or joint funding by several sponsors) are becoming increasingly popular. One example is the Think Tank Lab, a network funded by DGAP, Mercator, MERICS and the Robert Bosch Foundation that brings different think tanks together to build a community of practice and foster an exchange of experience between German think tanks to allow for effective collaboration.

Federal ministries like the German Ministry of Environment support think tanks by funding individual research projects, but only a few think tanks receive core funding from the government. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), for instance, provides regular funding to a selected number of think tanks such as DGAP and SWP, who we have learned anecdotally receive upwards of 30% of their funding from the MFA.

Both federal and state-level governments make institutional funding available to academic institutions, meaning that all others compete for project grants. DGAP is both government and privately funded, which helps maintain its independence. Individual projects as well as donations and membership fees from private members and institutions account for most of the funds they receive.

A marginal role is also played by non-profit organisations, the EU and the UN, foreign governments (primarily the Japanese, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian governments), and in exceptional cases by businesses, especially industrial firms. For instance, Japanese funding to German think tanks is based on what those two countries can do together (i.e. organise joint events on cybersecurity or on more general security threats coming from China; host exchange delegations). Japanese funding typically comes from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which has a particular interest in China.

Business-related foundations like the Robert Bosch Stiftung, Stiftung Mercator, Siemens Stiftung, Deutsche Bank Stiftung and others seem to have better and more long-term funding available for think tanks. The availability of funding provided by political foundations, on the other hand, largely depends on the success of the party.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

The demand for independent research and evidence is no less great today than it was in the post-war era when the think tank tradition began to take root in Germany. Although think tanks are increasingly seen to contribute research to inform debate, provide research analysis and, on certain issues, provide policy options, the extent to which think tanks influence political decisions is less clear. For example, decision-making in the German development cooperation system is either initiated and organised by the German government, or devised and implemented independently by various other players (e.g. GIZ [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH], Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau [KfW], municipalities, NGOs, churches and foundations).

Competence and credibility are two prerequisites that give think tanks access to both decision-makers and opinion-leaders. Within parliament, a relatively small number of them are occasionally called upon to participate in policy consultation processes by invitation to join parliamentary committees and fill in “knowledge gaps”. Parliamentarians reach out to think tanks to fact-check and acquaint themselves with new topics, and also appreciate the strategic recommendations offered by policy institutes. For example, energy policy and digitalisation are thematic areas where governments commonly seek policy insights from think tanks. Think tank policy recommendations in foreign affairs, on the contrary, are not that frequent, though DGAP and the SWP are the recognized and go-to players in this field. The SWP is perceived as the preferred partner to provide effective policy recommendations through discreet advice that often ends up being the official German foreign policy stand.

More recently founded and well-established transnational policy institutes such as the German Marshall Fund or the European Council of Foreign Relations (ECFR) are occasionally called upon to provide policy advice but not usually through official channels (i.e. parliamentary committees). These connections happen more through informal networks and through events and policy dialogue platforms. Conferences on questions of foreign and security policy are also being staged by foundations and international network organisations, such as the Munich Security Conference. In addition, Germany’s foreign intelligence service also increasingly sees itself as having a political advisory role, while some ministries fund in-house research departments. Do-tanks and activists do not appear to play a significant role for policymakers and the government, but are more visible to the public opinion.

The Centre for Feminist Foreign Policy has been rather successful and is reported to be influential, thanks largely to the rather personalised outreach model of its director, Kristina Lunz. Polis180 has a very interesting do-tank model and is somewhat influential, recognised for their promotion of young think tank talent. Political foundations tend to be quite influential, as they have more immediate access to policymakers and party structures.

When it comes to political party influence, German politicians expect to be advised in a comprehensive, credible and honest way by researchers or consultants whose political philosophy is close to their own. Here, the relevance and quality of think-tank products are decisive. However, politically affiliated think tanks are best positioned to influence political parties because they have deep networks (know the key players). This insider knowledge enables them to better meet demand by providing not only policy advice but political advice that independent think tanks are not positioned to provide. Having said this, most parties are looking for evidence from a variety of sources and seek a diverse, plural evidence base to inform decisions. For economists, influential voices like that of Marcel Fratzscher, former head of International Policy Analysis at the European Central Bank and current president of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW), is perceived as the person who influences the new government and the German Social Democratic Party in power.

A good indicator of think tank relevance and influence is when a think tank researcher is invited by a federal ministry to discuss specific topics or receives an invitation to attend parliamentary committee meetings. For example, Mercator Stiftung is regularly invited to participate in these spaces. Transnational think tanks on the other hand, are not typically invited to parliamentary committees. +

One common characteristic of the staff profiles within think tanks is that people working in these institutions generally have a strong academic background. In Germany, one either works in a think tank or in policy or one is in politics. There is no revolving door culture. When it comes to political foundations this differs, as revolving doors between party and foundation are seen more often (as in the case of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung).

Previous

Previous