Top take-aways:

- Most think tanks are government-affiliated or are under the influence of large corporations/chaebols.

- Think tanks are prolific and influential in Korea and are a government go-to. However, they have been criticised for being too close to government and lacking independence.

- The private sector may have a more limited role due to political scandals and scrutiny in recent years.

- There is a revolving-door culture, and senior-level ministry officials are often appointed to think tanks.

Jump to:

Overview of Korea’s think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 50

- Average age of think tanks: 33 years

- Top three cities: Seoul (38 think tanks), Busan (3 think tanks), Gyeonggi-do Jeju & Seojong (2 think tanks each)

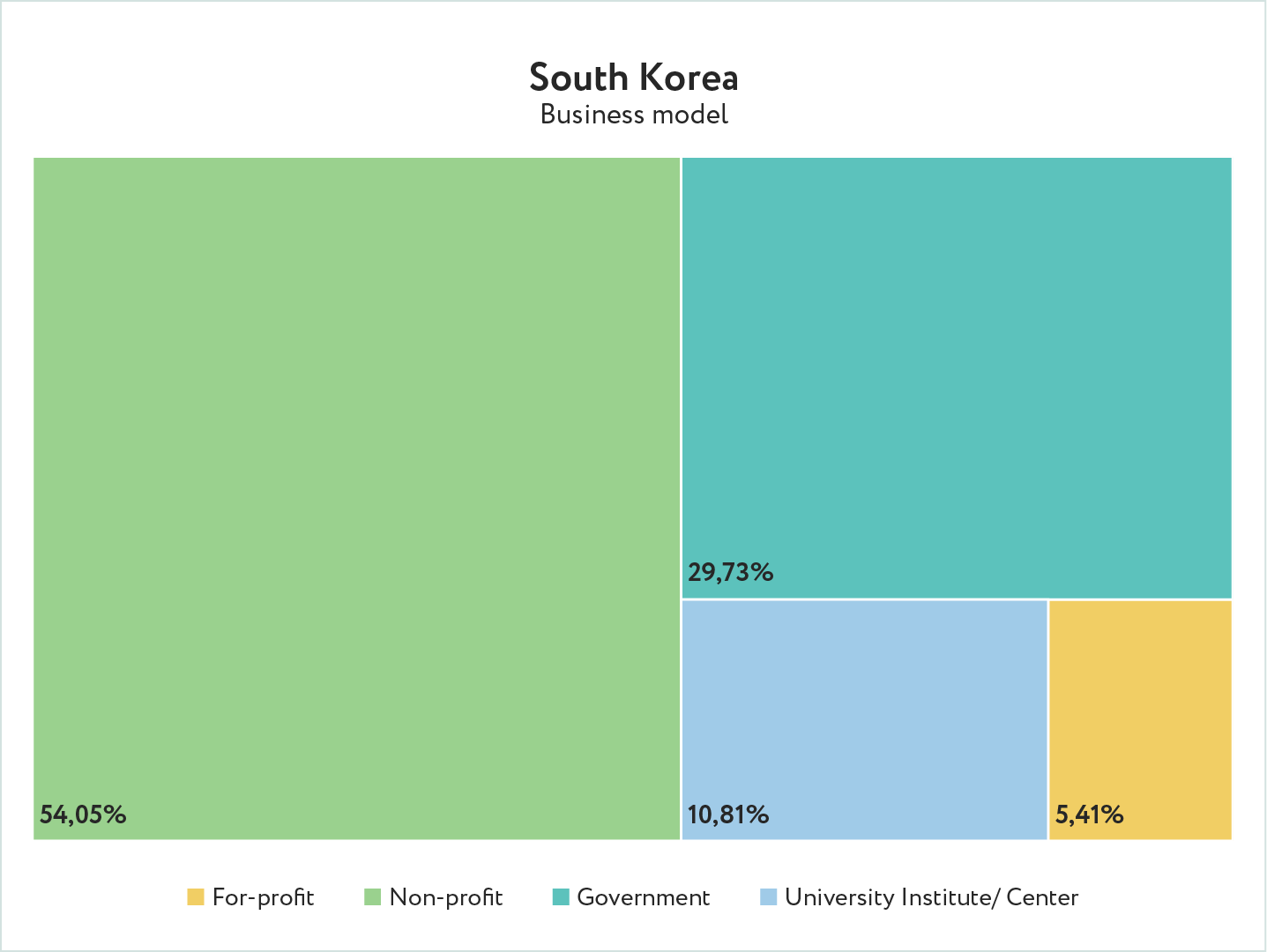

- Business models: Non-profit (54.05%), government (29.73%), university institute/centre (10.81%) & for-profit (5.41%)

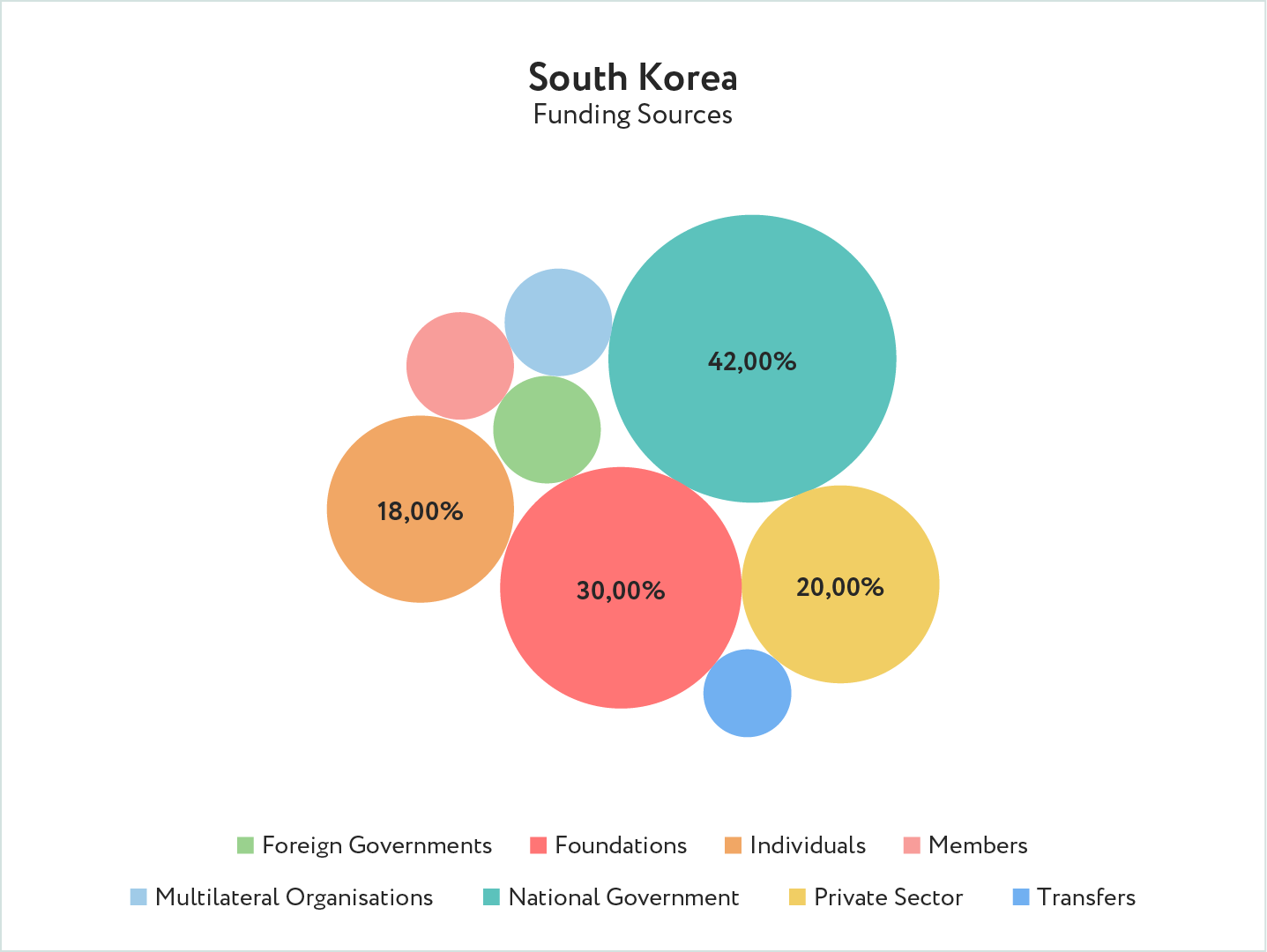

- Top three funding sources: National government (42%), foundations (30%) & private sector (20%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in South Korea were created between 1980 and 1999

- Staff size: About 20% of Think Tanks in South Korea have 46 or more staff members

- Leader’s gender: Male (75% ), female (22.5%) & both (more than one person) (2.5%)

- Average % of female staff: 1%

Country context

Presidential elections were held in March 2022 and the People Power Party and its leader, Yoon Suk-yeol, came to power to replace the Moon government.

Think tanks are centralised in Korea; many research institutes are under the influence of the government, either directly or indirectly. They have historically lacked autonomy and tend to be influenced by the administration or government they receive funding from and are affiliated with.

As a result of this landscape, researchers need to maintain and strengthen networks with the government and large corporations in order to get research projects commissioned by them. There is criticism that the heads of state-run think tanks, or chairs of the board, are often appointed and align research with the regime’s policy targets. One respondent observed that the “results from the same research are usually changed as the regimes change”.

Research institutes operated by large corporations, also known as chaebols (the sprawling, family-run conglomerates that dominate South Korea’s economy), also tend to have a strong influence in Korea, particularly those run by large corporations such as Samsung, Hyundai, and Lotte. There are also alliances of voices from large corporations that exert policy influence. However, in comparison to Japan, the private sector may be viewed as less important.

Due to many political scandals and scrutiny, including past presidents serving jail time due to their private-sector affiliations, politicians do not tend to work closely with business leaders. They are careful to keep their distance from the private sector.

Think tank characteristics

Think tanks are prolific in the South Korean landscape. Many policy research organisations in Korea focus on economic development and security matters and most research is done in public think tanks. There is a strong emphasis on the knowledge-based economy and, according to one respondent, think tank research is generally considered high quality. However, it is also essential to note the intention of the government to obtain evidence to support public policy planning and back its reforms.

There is a revolving-door culture, and senior-level ministry officials are often appointed to think tanks. As two examples, the current president of the Korea National Institute of Health (KNIH) used to be a government official in the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the former chair of the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHID) is the current Minister of Health and Welfare.

In terms of themes, the global health agenda is not of high interest to Korean decision-makers, so actors such as GR Korea (consultants to the BMGF) are working to raise the importance of this agenda. While Korea is considered a high-income, advanced country it also faces challenges, particularly regional political and security issues related to its borders with North Korea. As a result, many think tanks provide policy recommendations in relation to these concerns.

With regards to funding sources, as many think tanks are registered as affiliates of government ministries (29.73%), respondents noted that “they follow the agenda and their budget is allocated under the ministry they are overseen by”. The dominant business model is non-profit (54.05%) as illustrated in the following diagram.

Across all think tank business models, the national government accounts for 42% of all think tank funding in Korea, including budgetary allocations, commissioned research, convening events, etc. The following visual illustrates the diversity of funding sources based on data from the Open Think Tank Directory.

Previous

Previous