Top take-aways:

- 2000–2008 was a boom period for think tanks in Spain. Today there is stagnation.

- Despite Spain’s decentralised governance, its think tank landscape is characterised by mostly Madrid-based, small-sized think tanks with a thematic specialisation.

- There are but a few consolidated, well-funded think tanks in Spain, such as the Real Instituto Elcano, ISGlobal and the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB). Both receive private and public financing.

- Foundations and think tanks from the private sector are the most prominent, while consulting firms have recently stepped into the research ecosystem to do think tank work.

- Even though there is government demand for research and evidence, think tanks generally have low political influence.

- Spanish think tanks have low media exposure and are not widely known among the general public.

Jump to:

- Overview of Spain’s think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of Spain’s think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 53

- Average age of think tanks: 23 years

- Top three cities: Madrid (29 think tanks), Barcelona (14 think tanks) & Zaragoza (3 think tanks)

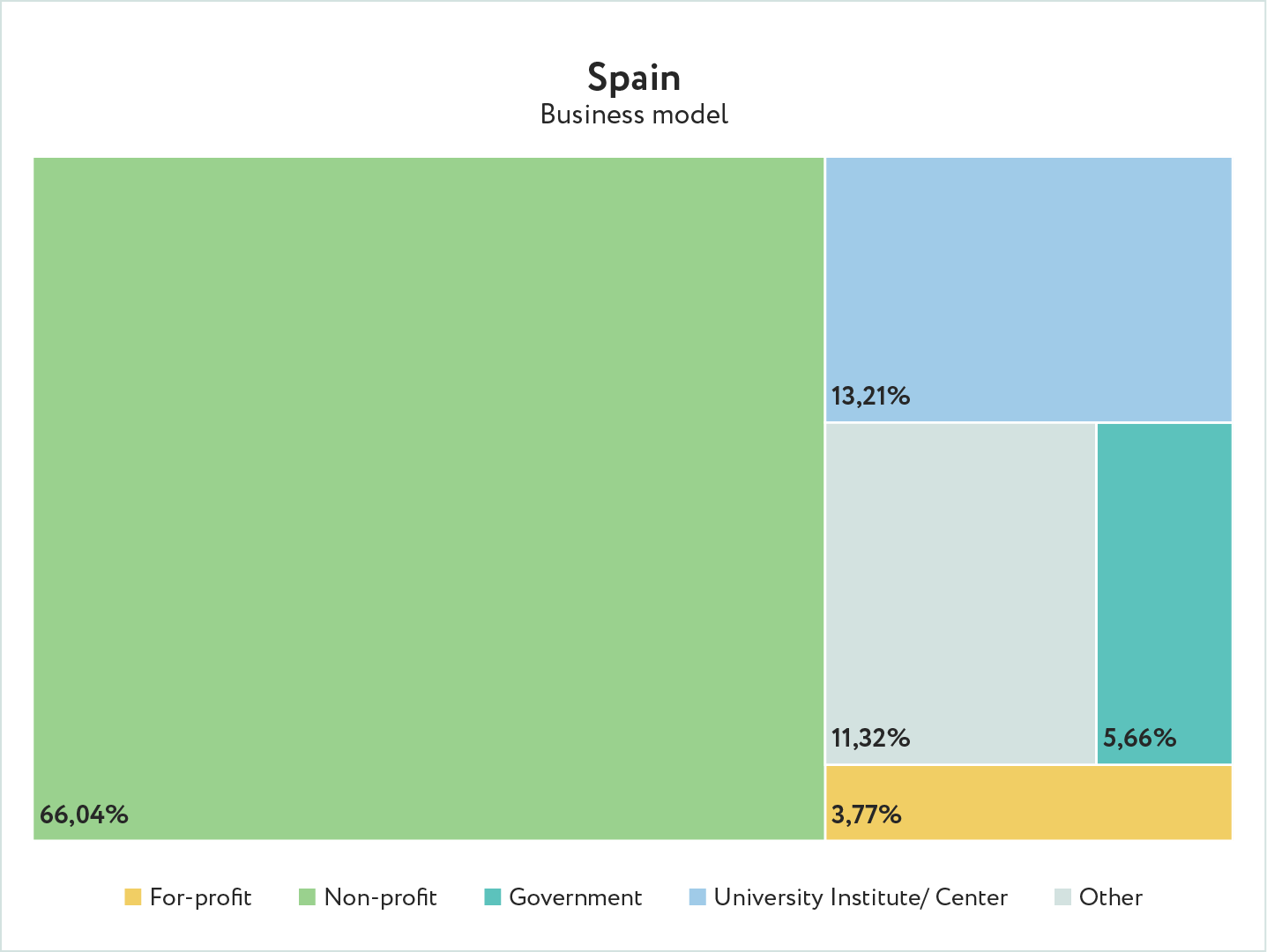

- Business models: Non-profit (66.04%), university institute/centre (13.21%), other (11.32%), government (5.66%) & For-profit (3.77%)

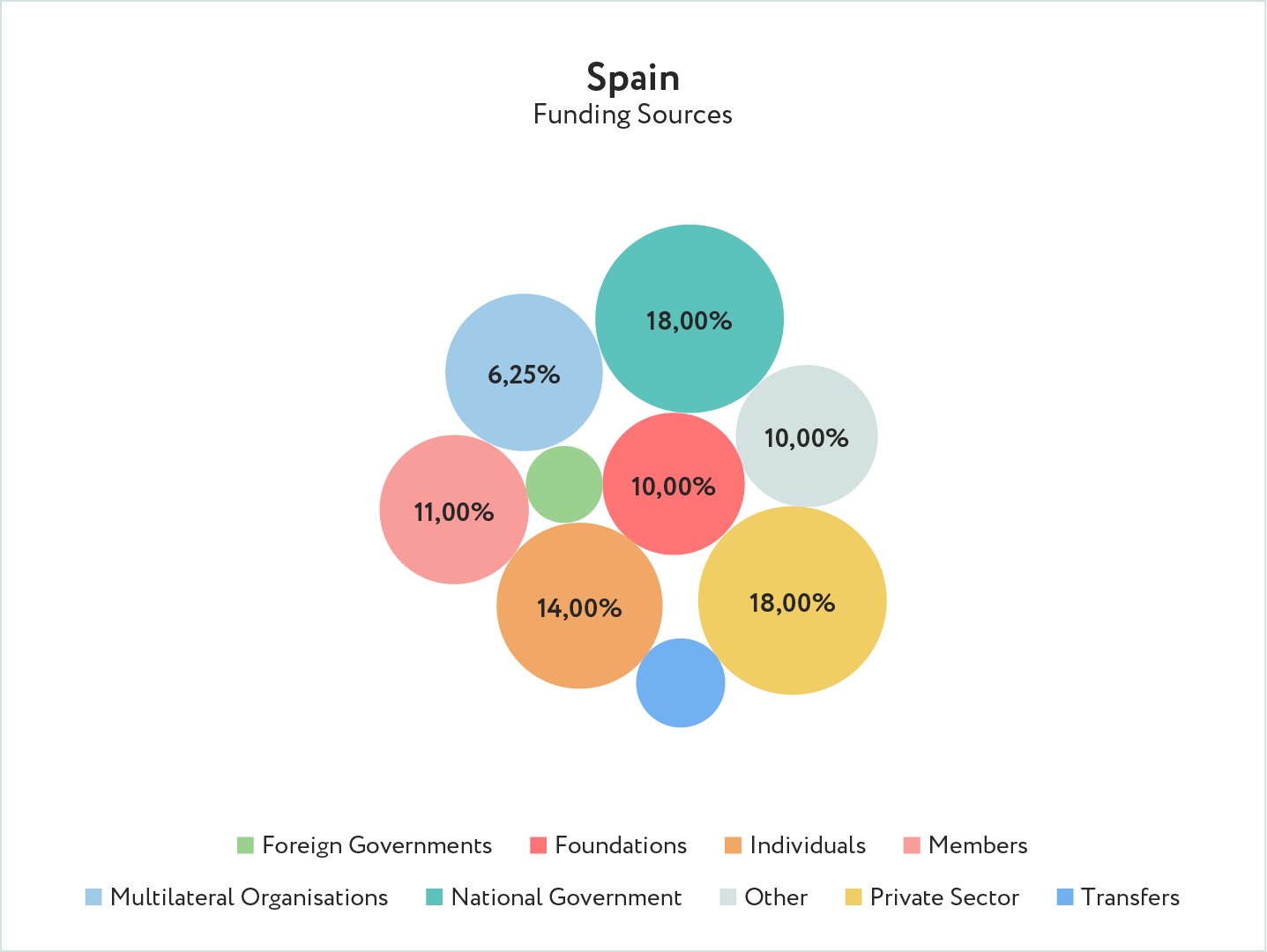

- Top three funding sources: National government (18%), private sector (18%) & individuals (14%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in Spain were founded between 1981 and 2011

- Staff size: About half of think tanks in Spain (44.44%) have up to 10 staff members

- Leaders’ gender: Male (85.42% ) & female (14.58%)

Country context

Thanks to its geographical position in the Mediterranean, its proximity to Africa and its historical ties with Latin America, the Spanish think tank landscape has a lot to offer as it is at the forefront of social rights and freedom movements. Spain is a respected and reliable partner that countries listen to, and due to many factors, has a high influence on European Union member countries.

Since it joined the EU in 1986, Spain’s research capacity has improved in breadth, quality and relevance. The country has evolved over the past 40 years from being a highly centralised federal model to a multi-layered state. Spanish citizens have a history of activism and express their position on government policies and programmes through different means, including mass demonstrations and internationalised public protests such as “No a la Guerra”(2003). This advocacy culture creates opportunities for think tanks to flourish as they offer an alternative pathway to influence political parties’ decisions as well as independent perspectives to inform citizens and stimulate public discourse and debate. Spanish politics have similarities with the confrontational spirit characteristic of the UK, where the two biggest parties attack each other constantly, and also share the trait of decentralised government with Germany.

In the years prior to the global economic crisis of 2008, there was a proliferation of think tanks, during a period of regional economic integration across Europe. After a peak in the number of think tanks established, there was a period of consolidation when big and influential think tanks like the Real Instituto Elcano prevailed, while others such as the Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (FRIDE) struggled to survive.

In recent years Spain experienced its second think tank “wave”, this time strongly characterised by consulting firms acting like think tanks playing advisory roles and bridging the public and private spheres. The lines between the roles played by think tanks and consulting firms have largely been blurred with actors like Llorente y Cuenca, a Madrid-based communications and public affairs consulting firm. These advocacy-type consulting firms are partly doing the work that long-standing think tanks like the Real Instituto Elcano used to do to influence policy.

In terms of policy priorities, gender equality ranks high on the Spanish political agenda with climate change, the digital revolution, global health, economics and inequality as additional issues of national importance. Due to Spain’s decentralised nature, think tanks not only follow these topics but also tend to constantly reflect on the relationship between Madrid and the centre and on how to remain neutral to local political issues that range from local elections to the Catalan independence movement. Due to historic reasons, discussions and debates often revolve around decentralisation and federalism.

Think tank research agendas are well aligned with government policy priorities, both internationally and domestically, as you can see from the table below. Foreign policy and European geopolitical relations are priority topics, particularly Europe–Russia relations, China, and global governance, democratic and political stability.

There are also other more domestic-orientated think tanks that focus their research agenda on local issues. With the onset of the COVID-19 in 2020, many policy research centres shifted their focus and new organisations aiming to inform policy responses on the pandemic, global health, and economic recovery, among other topics, have emerged. Dr Antoni Trilla represented the scientific think tank IS Global when advising the government of Spain throughout the emergency. The country has good knowledge and extensive experience in the field of public health and Spain’s praised universal health system is a hot issue. Topics discussed in public debates and the media typically include pension system reforms and universal medical coverage financing and debt.

Think tank characteristics

Most think tanks in Spain have grown under the auspices of public institutions, big private companies or universities and the majority of them are non-profit foundations (see table below). Consulting firms, private and political foundations and a selected number of universities also compete with independent think tanks.

Historically, Spain, like Germany, is a country where political parties have built very powerful partisan think-tank-like foundations that provide research, analysis and policy options that are ideologically aligned. As for their roots, it is common to see partisan foundations like Fundación para el Análisis y los Estudios Sociales (FAES) linked to the conservative Popular Party, Fundación Pablo Iglesias linked to the social-democratic Socialist Party (PSOE), or Fundación Galiza Sempre linked to the Galician Nationalist Bloc, while others have first-tier politicians on their boards.

Therefore, the Spanish think tank landscape is characterised by strong connections with political parties and fewer fully independent think tanks.

Newer think tanks like Political Watch have recently emerged linked to political opinion, and their staff is characterised by young, well-prepared teams who are savvy on communications and take good advantage of social networks. Looking into intercultural promotion, the “Casas” model also carries out think-tank-like activities. These are Spanish public institutions established in the form of cultural centres in collaboration with other governments with the aim to serve as a space for knowledge and studies dissemination, focusing on specific geographical regions of the world (i.e. Casa de America, Casa Asia, Casa África). They disseminate knowledge on political diplomacy, economy and business while fostering cultural relations.

From an economic point of view, financial and human resource constraints have crippled Spanish think tanks, especially since the 2008 financial crisis. While a second wave of think tanks emerged in the past decade, the onset of the current pandemic has stifled think tank funding, resulting in instability in maintaining qualified researchers. Competition among Spanish think tanks has become increasingly fierce and survival often depends on the think tank’s media visibility and ability to gain exposure and influence public debate and discourse.

Government funding has been on the decline over the years as the country has had to balance its spending after the 2008 financial crisis and recent investments in think tanks have all but dried up as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. One positive sign is that the country is currently on track to receive substantial EU funding to help finance the high costs of the pandemic recovery, a bright spot for future think tank funding.

In Spain, there are but a few consolidated, well-funded think tanks such as the Real Instituto Elcano and the CIDOB. Both receive private financing from companies and public financing. Public resources dedicated to policy research in Spain are typically channelled through competitive research projects within universities and research centres such as the Higher Council for Scientific Research and to specific research support schemes distributed by the 17 autonomous communities.

With an almost non-existent philanthropic community and a powerful subsidy culture based on government payments to specific industries, Spanish think tanks typically receive funding from the following sources:

- The IBEX 35 (the most important companies from the Spanish stock exchange). Big businesses in Spain are often represented on the board of trustees and they finance think tanks because they possess the financial capacity to do so along with an interest to influence policy and regulation.

- Financial sector foundations. The Fundación La Caixa, which belongs to the Barcelona-based “Caixa Bank”, one of the most important banks in the country, is a source of funding for some think tanks. According to OECD, Fundación La Caixa is among the 28th-largest foundations in financing for development volume (despite most of its funding is channelled domestically to fight poverty and social exclusion in Spain).

- Government public funds are very limited and fragmented, and to access them think tanks have to go through competitive procurement processes. Only think tanks that are already familiar with the requirements typically get awarded the grants. Interview informants reported that there are funds available from line ministries such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Defence.

- A common practice in Spain is for think tanks to receive in-kind funding from collaborators for their services, for example, paying for dinner when hosting an event with a private foundation or a public institution.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Generally, the Spanish government is quite active in the demand for policy research and there is a strong perception of a willingness to make decisions in an informed way. As one informant reported, “government advisors are very open and proactive to receiving data, research and analysis” from various sources, not only from think tanks. One example is Médicos del Mundo, an NGO that produces an annual report about health in the Spanish Cooperation System, which is closely followed by the Spanish government. There tends to be greater demand for input from foreign policy think tanks and political think-tank-like foundations. However, despite the openness of many government agencies and parliament to source independent research and analysis on a range of policy issues, this does not necessarily translate into policy influence.

Compared to other countries, respondents reported that think tanks in Spain have little policy influence and are largely unknown to citizens. Depending on the government in power, greater consideration has been given either to consulting firms, temporary appointed experts panels, trade unions or institutes that primarily conduct research. Historically, the category of political party foundations has been the most dominant since they are established and funded by political parties. In Spain, employers and unions have a lot of power when it comes to influencing governments. The big IBEX 35 companies are very influential, and in certain moments of crisis, social movements like the “Indignados/15-M” can also become quite influential. More specifically in the development cooperation and humanitarian area, NGOs and networks such as Coordinadora ONG (CONGDE) play an important role in policy formulation.

Relevant voices on foreign policy issues, aside from Elcano and CIDOB are those of the Fundación Juan March and Fundación Alternativas. Increasingly, consultancies like Llorente y Cuenca and the more recently founded Acento lead think tank advocacy work on topics related to politics, trade, elections, the digital revolution, and the green new deal. Academic institutions like Instituto Empresa, a well-connected private university that hosts many international students, has established a highly influential global governance programme under the leadership of former secretary of state for global Spain, Manuel Muñiz. Notwithstanding this particular example together with former Minister of Health and State Secretary for International Cooperation Leire Pajín, who currently works at ISGlobal, there is no such thing as a revolving door culture. Revolving doors exist between government and private companies but are rare between think tanks and the government.

Previous

Previous