Last week I attended a meeting of members of the Latin American Initiative for Public Policy Research (ILAIPP) or Iniciativa Latinoamericana de Investigación para las Políticas Públicas, supported by the Think Tank Initiative and hosted at GRADE, in Lima. One of the inputs to the event was a presentation of a pilot to test the usefulness of the Return on Investment method for evaluating the impact of think tanks. I tried this before for a project for DFID in relation to its efforts to influence health policy in developing countries and in multilateral agencies. It was an interesting attempt but it did not yield conclusive results nor was it at all useful to know what worked and why. If anything, any lessons learned from the exercise came from the qualitative aspects of the study.

Besides the ROI we also looked at Social Network Analysis and Outcome Mapping. If you ask me there is a great deal more value in exploring Social Network Analysis than any other method.

ROIs, but even better, Social ROIs, can be useful if:

- They are conducted ex-ante;

- It is possible (and appropriate) to monetise all costs and benefits;

- There is a clear (or as clear as possible) cause and effect relationship (e.g. it works for building a road or reallocating resources); and

- They include options from which to choose

But when it comes to research and the impact (terrible word, I know) it has on policy (too broad, I know) none of these conditions are possible:

- It is impossible to know how long ‘influencing’ will take or how long or how exactly an idea will become policy, then action, etc and so it is not possible to do an ex-ante ROI;

- Costs and benefits cannot be easily calculated (should we consider the training of the researchers, the years of data collection and analysis that led to an insight that led to a study, etc.?) or monetised (what would think tanks dedicated to promoting democratic institutions, human rights, etc. monetise? Most would, no doubt, focus on an issue not because of the return because the issue is important -of moral desert).

- There isn’t a clear cause and effect relationship; and

- Think tanks do not have ‘options’; at most they can only do what they have the capacity to do.

There are other reasons why ROIs are not the right tool for think tanks, including:

- They create incentives against initiatives that have low possibilities of success -but may be none-the-less important;

- Since every case is unique it is not possible to compare them using the same 4, 5 or 10 (etc.) criteria and therefore each initiative would have to be studied on its own and to such a great detail that it would be simply impossible for any single think tanks to do so without spending great sums of money;

- As a method to assess the performance of a think tank the ROI is only useful if it is applied to all the initiatives of the think tank and not to a ‘sample’ of them. Imagine an investment fund manager who only reported on the returns of some of the fund’s investments and using those to make claims about the performance of the entire portfolio. If a think tank wants to use ROIs to make claims about the organisation’s performance then it would be forced to undertake an ROI for every single one of its interventions;

- As a tool for learning it is rather useless -unless it is used as an excuse to assess the contributing factors for change- and an expensive one, too; and

- Because it opens up a door that think tanks should try to keep closed. Think tanks should try to articulate their value to society in terms that do not hide the complexity of their roles. The argument that ROIs can help sell think tanks to ‘simple minded’ funders is not only flawed but also dangerous: 1) these are not the funders that think tanks should be working with, and 2) if not the think tanks, who can educate the funders?

There is already a literature on the rates of return to research which concludes, among other things that:

the main challenges facing the measurement of the rate of return to research:

- The attribution problem -did the research influence policy?

- The identification problem [alone] -did the policy intervention or reform lead to the desired/observed outcome?

- The measurement problem -can benefits of the outcomes be quantified? [and monetised?]

Are ROI’s useful for think tanks at all? Yes. Think tanks can use ROIs to assess policy options and recommend the best (or more desirable ones) to their policy audiences. In other words, ROIs (and other such methods) can be useful research methods on which to base their arguments and advice. So, by all means, do look into them but don’t use them for what they are not useful.

An alternative to the ROI: the Force Field Analysis (although common sense will do, too)

Is there a tool (I am not a fan of tools but…) that could do some of the things that ROIs’ are supposed to do? Well, Force Field Analysis (FFA) is a tool that can, unlike a Return on Investment (ROI) evaluation, be done ex-ante (to help decide), be used for monitoring (to learn and adapt), and offer a sense of whether all that was done was done properly (to evaluate).

It won’t quantify (in any scientific way) the level of contribution to a change (not will it attempt to) but it can offer some sense of it. It can certainly help to tell a reliable and nuanced story.

The FFA described below was improved by Ben Ramalingam and was later adapted over a series of workshops with researchers, advocates, policymakers, communicators and others. The (adapted) text and diagrams below are taken from a How to Note on Policy Influence that I drafted for DFID in 2010 -so I apologise for any self-referencing:

Force Field Analysis: using it for planning

Using a force field analysis can help identify and understand the forces for and against a desired change in an actor, and which of those forces a think tank can have the biggest influence on. It is not be necessary to conduct a FFA for every policy objective, though, and ideally organisations should learn to prioritise those objectives and actors which are the most important for their mission and where they are unsure of their influencing capacity.

In order to use a FFA effectively, the think tank needs, above all, a clear desired change. The more specific the change the better -and the change ought to be linked to a particular actor (a person, a team, an organisation) with decision-making capacity.

If a flip-chart is used then:

- Write the objective in the middle of your diagram (see diagram below). For example: “The Vice-Minister for Transport signs-off, before the new budget is approved, a USD100 rural roads programme focused on the Eastern Province in accordance to the proposals made our research programme.”

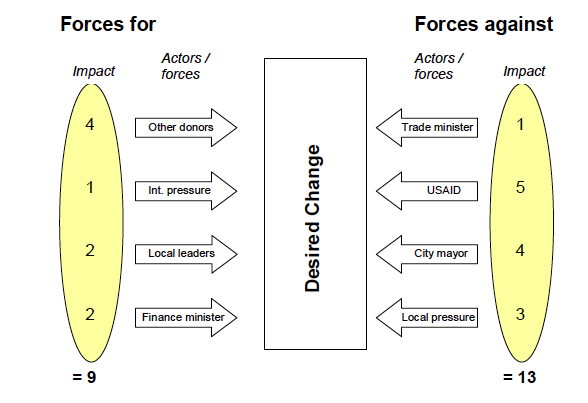

- Draw up a list of all forces for the change i.e. that will influence the particular actor and its willingness/capacity to change. Sort them into common themes and write them on the left hand side of the change. Forces can be people, events, knowledge, processes, structures, etc.The list can be as long as necessary and it should reflect the specific nature of the change and its context. If the change is very clear the list of forces will be easier to identify.

- Then repeat this process listing all forces against the change i.e. that will hinder the desired change.

- Next, making sure you consult widely, rate the strengths of each of the forces, ranging from one (weak) to five (strong). In some cases, a force may have a force of zero, meaning that while it has no effect ‘right now’ it may have an effect in the future. This could be based on experience, the literature, risk assessments, etc. In some cases, too, the 1-5 scale may not be enough. Some forces are simply much higher than all others and this has to be made clear. In these cases, it is possible to break the rule and rate them as 10 or 15 or maybe add a * next to the force to suggest that ‘even if all other negative forces were gone this would be enough to prevent change.

- Total up all the forces for and forces against to see how the overall numbers compare. This indicates how easy or difficult you think it will be to bring about the change. It is not a scientific calculation but, if the forces and rates are based on sound evidence (from various sources) then the assessment of difficulty will be as accurate as it could ever be.

Here is where Ben introduced a new dimension. The steps so far have given us a sense of the factors that may cause a change to happen or not. It also gives an estimate of the degree of difficulty of that change. Anyone doing a FFA should expect the balance to be negative or else they should consider that they have chosen to target something that was going to happen anyway.

The FFA as it was originally developed did not provide a sense of what to do next. The next steps can help in this respect:

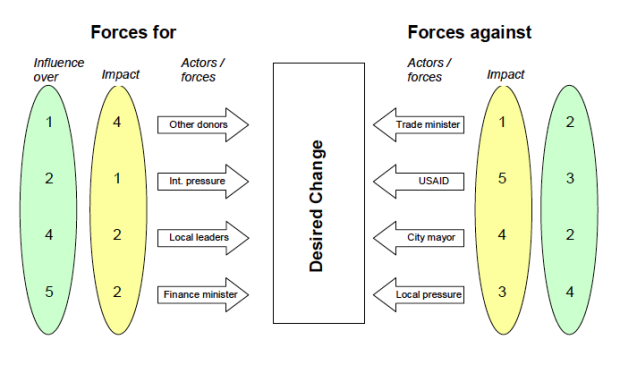

- Next, the think tanks can consider their own influence over each of the forces. They can rate this influence from 1 (weak) to 5 (strong) for each force, considering:

- Where can they strengthen weak forces who are for the change, to increase their impact?

- Where can they reduce the impact of forces who are against the change, by either decreasing their impact or influencing them to change their attitude or behaviour?

- The think tank can develop its strategy by focusing on the opportunity to increase weak positive forces and reduce strong negative forces.

- During this process they need to think about their influence through other actors and forces as well as their direct influence. Although they might not have a lot of influence over an actor or force directly, they may still be able to change their behaviour by using another actor or force that the think tanks do have a lot more influence over.

Completing a FFA can help an organisation or team decide what actions would be required to influence others to achieve their objective and whether these actions merit the necessary resources -or the resources they have. They may find that it will require a disproportionate amount of effort to change an organisation’s or group’s behaviour, even if they had been previously prioritised; alternatively, they may find that they have a lot of influence over a person, organisation or group (or process) who they had previously discounted as being immovable or relevant.

If after conducting a FFA the think tanks decide that it is unlikely that they could influence a desired change in an organisation or group, it can be helpful to consider that:

- If they can’t influence them in the way that they originally wanted to, can they influence them in another way? For example, if they can’t influence someone to support their policy recommendations, instead could they influence them not to directly block them?

- If they are trying to influence a large change in a particular organisation which they now think is impossible, could they try breaking it up into intermediary (shorter-term) changes and see how possible each step would be to influence?

Using FFA for ex-ante decision-making

Ideally, a think tank would do several FFAs: for different objectives. By comparing them it can make a decision as to which objective(s) deserve(s) its efforts. It may very well choose the hardest one but there will be a record of the others and of the opportunities that they offered the think tank. This decision can be evaluated in the future.

Using FFA for monitoring and evaluation

To monitor, the think tank can repeat the FFA process during the influencing effort. This may involve adding new forces (that emerged or became clear during the influencing effort it self), chancing the strengths of the forces, and changing the influence of the think tank on the forces.

All of theses changes demand analysis to decide why they happened. It would be a mistake to assume that they changed because of the actions of the think tank simple because the think tank sought to change them. And this should be clear from the fact that think tank is likely to be focusing its attention on only a small portion of the forces affecting the desired change.

The analysis in turn should provide the think tank with additional options and choices which can be evaluated later on.

FFA can also be used to evaluate the intervention. It should be possible to:

- Analyse the strategic capacity of the think tank by reflecting on the choices made by it at the start (comparing options) and during the monitoring process (adapting the strategy);

- Determine if the forces that the think tanks targeted directly changed -and to describe what the think tank did and how it may have contributed towards those changed;

- Draw lessons from each intervention by determining which actions led to which changes; and

- Learn more about the context and the causes of policy change in the sector or issue under focus as the listing and rating exercise demands a great deal of research, intelligence gathering, analysis, and critical thinking. All of this can be incorporated into the think tank’s collective knowledge for future initiatives and action.

But it won’t provide a number nor should be used to attempt to attribute a change or impact to a single actor or intervention.