The more aspects of your day to day operations get digitised, the more important IT-security becomes. The risk of a fast-paced ‘shock digitisation’ is that security becomes an afterthought, because in the short-term, functioning systems are more important than secure ones. But IT security, in general, is a long-term process and not a quick fix.

It’s also a team sport. The day-to-day behaviour of all staff impacts your security level. For example, if your employees are unaware of risks or untrained in dealing with phishing emails, they are more likely to click on a malware attachment and compromise your entire operation. It is often said that IT security depends on the weakest link in the chain, whether that’s insecure software or users.

Being a team-sport depends on the coach too. Until recently, IT security did not rank too highly on the priority lists of executives, because spending money on threats that might never materialise seemed rather unattractive for cost-conscious organisations. Fortunately, more executives have become aware that they must up their IT-security game.

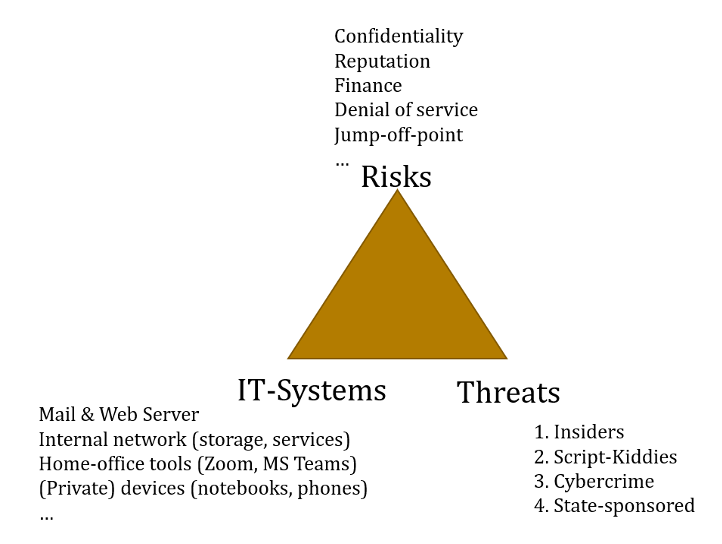

Of course, not all think tanks are alike and some have stronger security requirements than others. Threat modelling is a practice to tailor security requirements to the particularities of a specific organisation. Threat models are typically composed of risks, threats, and the individual IT-infrastructure set up. IT infrastructure (i.e. the software and hardware you use) has to be tailored to specific risks and threats.

What are your risks?

In IT security, a risk is a potential for loss, damage, or destruction of an asset as a result of a threat exploiting a vulnerability in your IT systems. In other words, it often entails losing something of value. Here, we’ve compiled a list of threats that seems most relevant for think tanks.

In our assessment, the biggest risks for think tanks lie in a loss of reputation. Your reputation, and therefore the trust you receive from the policymakers you advise, the public you inform, or the human sources you rely on, is your most valuable asset. It can get harmed, for example, if an internal communication gets leaked. Remember the ‘fuck the Europeans’ intercept of US Ambassador Nuland in 2014 that was leaked to the press?

As we move work to video-conferences, a topic we will explore in part four of this series, Zoom calls come with their risks of interception and leaking, or unwanted third parties joining and recording your conference calls.

There are also concrete financial risks for many small and mid-size organisations. There are classic cyber-crime schemes like CEO fraud, where someone pretends to be an executive and orders its budget office to initiate a banking transaction to some dubious entity. If you depend on third-party funding, your financial assets might be at risk if you or your donors get hacked. Remote work also produces unique challenges, as your accounting department may access sensitive accounting systems from insecure private computers at home.

There are also personal risks for your employees or sources. Information could be stolen to blackmail your organisation or individual employees. State-sponsored cyber criminals in authoritarian regimes and countries with limited statehood can also target individuals with harassing tactics like trolling or doxing (leaking personal information such as a private addresses to intimidate and quiet targets or dissenting voices). Often women are particularly targeted by these types of tactics.

And let us not forget vulnerable sources. Think tanks working in authoritarian regimes rely on interviews and first-hand witness reports for their research. In areas where government transparency is low and access to information is limited, whistleblowers are often a primary source. Your sources could suffer if you cannot protect their identity because you use insecure communication channels or your IT system gets hacked. Likewise, if you are involved in Track II diplomatic processes, like conflict mediation between formerly warring parties, the identities of stakeholders might be at risk.

There are also operational risks: work or data could get stolen. For small and mid-size companies this could be the loss of intellectual property due to espionage of internal Zoom calls or the email server.

These reputational, financial, personal, and operational risks can overlap of course.

What are your threats?

A threat is an action or inaction likely to cause damage, harm or loss. A threat is something or someone you are trying to protect against. The following threats, in ascending order, can be relevant for think tanks.

A ‘script kiddie’ could break into your system just for the fun of it (or rather, for the ‘lols’). For example, ‘Zoombombing’ has already happened at many online events where the webinar link was posted publicly on Facebook or website.

A cyber-criminal gang could want to extract money from you by encrypting all your internal files with ransomware and demanding a ransom payment with Bitcoin. Ransomware is an increasing threat in IT security, hitting universities, hospitals, and research institutions worldwide.

As with all emails, invitations to Zoom events can be faked and include ransomware somewhere behind the link to join a meeting. Such a denial-of-service attack would be a worst-case scenario in times of remote work, as it certainly would halt all operations.

An individual or organisation (or a state) could try to shut down your website in retaliation, for example, for a critical paper you published against a government. These retaliation practices are not uncommon. There was a case of doxing in Germany where a single hacker compiled target lists of figures in the public domain, collecting open-source intelligence like addresses and phone numbers, and leaking them to the public because he wanted to send a message.

A disgruntled employee with access to sensitive information is often overlooked as threats. Imagine someone’s contract wasn’t prolonged and now they threaten to sell internal information to the press.

The most challenging adversaries for think tanks are intelligence agencies. Both foreign and domestic intelligence agencies in authoritarian regimes might be interested in you because you work on a specific region or topic of interest, or because you have an office abroad. This has to do with perceptions. You may operate under the assumption that you don’t have anything interesting to hide, no access to sensitive government documents or communications. But think tanks, especially those that are close to the government or receive public funding, are automatically interesting for foreign intelligence agencies. So, think tanks should always assume they are targets.

You could be used as a jump-off point for cyber-attacks by foreign or domestic intelligence agencies to reach other, higher-value targets like politicians. This means attackers are not necessarily interested in you personally, but in the people in higher echelons of power who you might have close contacts with. Thus they could be after your email contacts or use your email identity to send phishing emails or malware attachments to your customers. NATO’s own cyber-security centre in Tallinn was a victim of such a scheme: allegedly Russian state-sponsored hackers tried to use the reputation and credibility of NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence to send a manipulated conference agenda to security researchers worldwide.

How is your IT infrastructure set up?

Your IT infrastructure determines your ‘attack surface’ – the ways someone can launch cyberattacks against you. This includes operating systems, software used, and the set-up of internal servers (file-, mail- and web-servers).

At the bare minimum, most think tanks will use some type of email system for internal and external communication, an internal network or storage system to save files, and potentially a website that is hosted somewhere.

Then there are your staff’s devices, the computers, printers, Wifi routers, and smartphones you use in your office. The last part of your attack surface is the software that you use. The more apps, tools, and digital processes you use, the more susceptible they become to hacking.

As you can see, unfortunately, the threat landscape for think tanks is complicated. You realistically can defend against script kiddies and organised criminals that hack for money. This requires some investment in your IT security and is a continuous process. But protection against fully-fledged cyber-attacks by intelligence agencies is hard to achieve, if not impossible.

Now that we’re familiar with the big IT security risks and threats, in part three of this series we look at what you can do to enhance your cybersecurity in the short, mid and long term.

Previous

Previous