10.00 am, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

I’m on a bus 5,000 miles away from London, reading about Cast From Clay’s study on democracy in the UK. They warn of an ‘irrevocably fragmented’ information environment. They say, the nature of informed debate has changed. Democracy is in peril.

I think, they could be talking about Sri Lanka. To my right, a passenger scrolls through their newsfeed in Sinhala, the language of Sri Lanka’s ethnic majority. Across the aisle, a passenger holds a newspaper with Tamil lettering, the language of the country’s largest ethnic minority. Long before Zuckerberg and talk of echo chambers, Sri Lanka’s information environment was considerably fragmented.

Yet, while Cast From Clay’s conclusions resonated with me, Sri Lanka’s context is very different to the UK. So, to remedy the issues that have plagued democracy in Sri Lanka, we’ll need fresh thinking.

Here, I’m sharing my own (fluid) thoughts on the Sri Lankan experience, drawing on Cast From Clay’s research. I hope this invites broader reflections on how policy researchers, particularly think tanks, can respond to the threat to democracy in different contexts.

A post-mortem of Sri Lankan democracy

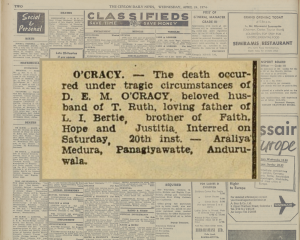

In 1974, Dr. Riley Fernando published a satirical obituary on the death of D.E.M. O’CRACY. This was published in a state-owned paper, following repressive state action. But one could argue that democracy in Sri Lanka died long before the 1970s.

As in the UK, Sri Lankans value democracy. But what this has meant in theory and practice has differed.

For one, ethno-religious minorities have a complex relationship with democracy – as Professor Ismail asked: ‘What, to the minority, is democracy?’ when popular choice is equated with majoritarian interests.

Civic participation in governance is also limited. People trust that their voices will not be denied at two sites: polling booths and protest sites. Over 75% of Sri Lankans will turn up to elect leaders and publicly express their frustration when leaders fail to deliver, despite being met with force.

Political bargains seem appealing in the context of dysfunctional systems, corruption and excessive state control. Public support for strong leaders and saviours even extends to those described as having ‘seven brains’. This suggests that people will tolerate some degree of democratic decay in exchange for anyone who can ‘save’ Sri Lanka. In total, 75.4% of respondents to a national survey confirmed this – as indicated through their desire for a ‘strong leader who wasn’t inconvenienced by elections’.

Sri Lanka’s information environment: old symptoms are worsening

As the old phrase goes: ‘democracy is a government by discussion’. Well, a discussion between the passengers I observed on the bus is highly unlikely. And one about policy is even less likely. They, like me, are exposed to at least two features of Sri Lanka’s information environment, which limit informed debate: polarisation and politicisation.

Polarisation

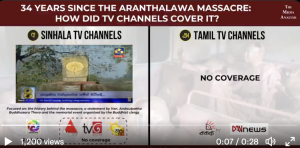

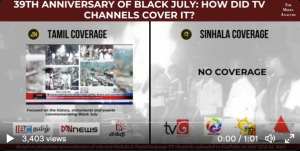

The Sri Lankan media is organised along three distinct language spheres: Sinhala, Tamil and English. Language, ethnicity and religion are linked in Sri Lanka, thus, so is the news. Policy priorities and issues in Tamil are not on the Sinhala media’s radar, or they’re reframed, and vice versa. Our discussion spheres rarely meet. Even during our collective cry in 2022 for ‘system change’, our reasons were entirely different.

Media silos, catering to the ethno-linguistic and religious concerns of the readership. Source: Verité Research, image 1 and image 2 (Content warning – images of death in the source videos).

Politicisation

The state’s ownership and regulation of the media gives it a near monopoly over narrative control. Alternative narratives have rarely succeeded. When censorship is the norm, it’s unsurprising that the majority rely on the stories related by friends and family. As the anthropologist Dr Thiranagama remarked: ‘the burden of proof was always on ordinary people to do this work of remembering.’

And the struggle today is not only one of knowledge suppression and sanitisation. The state’s apparatus have become far more sophisticated, with proxy voices doing its bidding (e.g., influencers, bots and private media).

Expert opinion is not free of these influences either. The culmination of the two forces – ethno-religiously inclined views and state control – meant that a racist COVID-19 policy was defended by globally recognised, local scientists.

Cast From Clay’s ‘Age of Instinct’ is here, but it’s arrived for different reasons in Sri Lanka. Public trust in Sri Lanka runs along a spectrum. It moves between an instinct to uncritically accept information (because it’s what we’ve been told or it reinforces our beliefs) and an instinct to be sceptical (because ‘credible’ sources have repeatedly breached our trust).

Equal access to unbiased and reliable information is important in treating these issues. But this alone isn’t enough for a healthy democracy.

Call in the experts

A handful of think tanks and policy researchers have proposed a different approach to reviving Sri Lanka’s ailing democracy. For them, talking to decision-makers isn’t enough. They see the value in getting more people involved in the process – if people’s views and ideas change, better systems and better-informed decisions can be made.

While such efforts are welcome, they often resonate with a small, English-speaking class. The wider public see think tanks as detached and as advancing an elite or western agenda, or they don’t know they exist at all.

These perceptions matter, especially at a time of crisis. People are less likely to support well-researched ideas if they don’t understand them, aren’t aware of them or don’t trust the messenger.

The good news is that experts still largely enjoy public support – much like in the UK. Broadening this support further may require a genuine commitment to sector-wide reflection and re-imagination.

One role think tanks can play is that of the trusted source. This involves acknowledging that greater transparency is non-negotiable in building trust. People want to know who is behind the research, how diverse they are, how inclusive the research process is and who funds it.

Think tanks can also be facilitators by fostering a common base for public reasoning and understanding. This may involve implementing communication strategies that bridge historically divided conversations or meaningfully engaging different language communities.

A greater challenge for think tanks is to become the architects of change. This requires moving beyond the realm of ideas, like Watchdog did. They went from researching flawed systems to designing Elixir, a solution to Sri Lanka’s medical crisis. Think tanks can not only envisage change, but also implement it by leveraging their capacity as change hubs.

As Sri Lanka enters another year of dealing with the fallout of poor governance, think tanks have a crucial decision to make. During last year’s protests, several policy researchers made efforts to better connect with the people. E.g., they convened educational teach-outs and discussions and placed informative posters at protest sites to reach new audiences.

At a time when Sri Lanka requires bold changes, institutions may need to be bolder in seizing the opportunity to guide public imagination towards a better-governed and more inclusive future.

To invert Cast From Clay’s words: ‘This is our old equilibrium, it is worsening, and we need to change it or risk succumbing to it.’