[With input from Cristina Ramos and Enrique Mendizabal].

The first online OTT Conference 2020 was held in March/April after the need to postpone our annual face-to-face conference (read about the process). Our second event was held in June, and the third and final event of 2020 was in November.

For our third online event, we tried a different approach: the first day was focused on conversations on the topic of ethics and integrity, and the second day was devoted to a series of workshops and fringe events organised by OTT and partner institutions.

OTT Conference 2020: the 3rd online event had 257 attendees from 44 countries +. At the start of the event, we asked participants if they thought ethics is a serious problem for the think tank sector. Out of 32 respondents, two did not think it is a problem, 12 think it is a problem in some cases, and 18 think it is a problem.

DAY 1

ETHICS AND INTEGRITY

Keynote and Q&A

Ethical dilemmas for think tanks: Drawing bright lines

Keynote: Ruth Levine (IDinsight)

Moderator: Enrique Mendizabal (On Think Tanks)

Key takeaways

In her keynote, Ruth reflects on the need for think tanks to be highly relevant in current policy debates. The challenge, she argues, is that it can be too easy to lose sight of the larger picture. Think tanks should consider their alignment to the governments they work with, or if they are better off allying themselves with opposing forces and being part of a larger shift in the policy space.

Admittedly, there is a standard discourse that think tanks are neutral- but everybody has ideologies. Transparency is a better approach than pretending to be neutral: it is better for think tanks to be clear from the start about what their belief is and what the role of governments is.

Think tanks should also be transparent about their funding and their activities: there is no strong-enough argument not to disclose who your funders are. To ensure credibility, think tanks should consider diversification of funding sources. How can they do this without compromising the integrity of their research agenda? Think tank leaders should try to make the case to their funders that supporting research programmes and research agendas is preferred over supporting specific projects. This is not possible for every case, but it does allow for a compromise between funders and think tanks in which funders invest on a particular area of interest and allow think tanks to be more flexible about their agendas.

As Ruth argues: think tanks are not powerless in their relations with funders. Think tanks are providing services and offering perspectives that are unique to them. Think tank leaders should own their power within that relationship and not make the assumption that it should be a submissive one.

From the chatbox

Resources:

Centre for Effective Philanthropy (CEP) report on multiyear general operating support

Transparify Integrity Health Check

Questions:

When we start a project, in our think tank, with the sponsorship of another organisation, we might face gaps and challenges which are needed to be focused. These issues are not in the interest of the funder of the project. What are the best strategies to find an organisation that specifically addresses the problem we see?

It would be great to hear Ruth’s additional thoughts on accepting funding from non-democratic governments. Whilst we understand the ethical dilemma, others argue that it is the think tanks’ role to keep the communications channel open when governments stop talking to each other. A way of legitimising the project could be to bring democratic governments to the table as a joint effort.

Some think tanks are usually “shy” to advertise who their foreign funders are (democratic or not). They tend to be afraid that they are publicly acknowledging foreign pressure to pursue a specific agenda. At the same time, funders want (and need) to be acknowledged to justify their funding. What do you advise think tanks to do when walking this fine line?

Funding diversification for think tanks is an important strategy to help think tanks manage tensions between different funders agendas and particular policy outcomes priorities, however, it can lead to mission creep. What are your views on how think tanks can stay true to their agendas while pursuing a diversified set of funder interests?

Some of the ethical decisions that Ruth has discussed are not easy to resolve on a priori grounds. Since this is a group committed to evidence-informed decision making, wouldn’t it be a good idea to collect some evidence on how these decisions work out in practice? (i.e. some case studies).

What the video to find out how Ruth answered these questions.

Parallel 1

Ethics in research

with Douglas Mackay (University of North Carolina), hosted by Norma Correa (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú)

Key takeaways

Think tanks don’t often consider the ethical implications of their research methods. Douglas Mackay has been reflecting on the ethics of public policy randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In this session, Douglas considered several guiding principles such as (lack of) consent of participants, social value, the role of community in deciding research, and randomisation and distributive justice.

Douglas starts by pointing out that it is important to have a systematic and sustained approach to policy research ethics as there is in medical research ethics, developing methods and thinking about it as a field of research- one that is a shared and inclusive space.

As Douglas refers, RCTs are not the only legitimate source of knowledge, this is one tool among other tools. However, to assess if they are ethical, there should be more discussion and focus on the guiding principles already mentioned.

Informed consent is one of those principles. It is an issue that needs further investigation as it is not always secured in studies. Douglas suggests that there is a need for a moratorium on policy RCTs until regulations are sorted out. Actually, the broader question is if informed consent is necessary and when.

Social value is another of the ethical requirements for medical research ethics. The research needs to promise value to society. Should this be a requirement for policy research ethics too?

Several of the participants in research do not get fair benefits from participating in these trials as those are not done thinking about their contexts. Douglas highlights the importance of starting to think about fair distribution linked to social value, for both medical and policy research.

From the chatbox

Resources:

The Oxford Handbook of Research Ethics

Questions:

I have a more fundamental observation on the ethics of policy research: What gives think tanks or social researchers the legitimacy for policy research. Do they draw it from their accountability to their grass root constituents? How do they claim to be the voice of the community or necessarily reflect the felt-needs of the community? Is this not a fundamental ethical dilemma?

On the issue of RCTs: Is this an ethical debate about how to do RCTs ethically? Or is there an ethical dilemma about running an RCT at all? (versus generating other types of knowledge/other approaches)

Watch the video to find out how Douglas answered these questions.

Parallel 2

Ethics and organisational partnerships

with Alba Gómez (European Council on Foreign Relations), hosted by Ajoy Datta (On Think Tanks)

Key takeaways

Partnerships between think tanks and other organisations are not always equitable and can create dilemmas and challenges for both sides. This may affect the overall equity of the policy research system in a country, a regional or globally. Alba Gómez, from the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), reflected on how organisational partnerships, particularly with funders, following certain principles and guidelines, could be more ethical.

Alba started by pointing out an aspect that was also referred to by Ruth Levine: it is important to take advantage and promote partnerships with funders as think tanks should see themselves as providing value. Alba reminded us that think tanks should not undersell themselves thinking that they are the weakest link of the partnership.

As it was mentioned throughout the conference, it is the utmost importance for think tanks to maintain independence and transparency. Think tanks should do their research on funders: to have a successful partnership, organisations need to share the same values.

The general public, the thinktankers, all stakeholders should be aware of who is funding who, the amounts and what for. The dilemma with data privacy is important and should be addressed, but there is even a bigger deal with the audiences, who are now even more preoccupied with issues such as credibility and trust.

However, these are not only aspects important to external audiences. Think tanks should have guidelines and communicate them internally. Alba highlights the importance of having a process on think tanks about funding and partnerships and maintaining that transparency within the organisation.

From the chatbox

Questions and comments:

What is included in your due diligence of funders? What are the most important things to know about them? How do you find out?

What about partnerships with non-donor organisations? How different are the challenges you face, including on the agenda-setting front?

What aspects of partnerships do you value the most? Apart from trust and core funding provided by funders, what else are you interested in?

Ruth Levine talked about think tanks as boundary crossers. Think tanks act as public intellectuals on one day and on the next day they act as private advisors to policymakers. Making sure that you’re not drawn to one side too much is key. Can you share how ECFR manages to find the right balance?

As a funder, I reviewed about ten investments that attempted some kinds of North-South research or policy partnerships. One major factor of success was the history of their relationship together: both institutional and personal.

Forced funder brokering rarely worked (I’m not sure if it ever did). The reasons for failure were many though: not recognising how long coordination and partnership development takes, disagreement on approaches, issues with funding flows, logistical issues (e.g. settling contracts and MoUs).

Watch the video to find out how Alba answered these questions.

Parallel 3

Ethics in reporting the work of think tanks

with Laura Zommer (Chequeado), hosted by Keith Burnet (Chatham House)

Key takeaways

Laura Zommer from Chequeado discussed how media organisations and think tanks should work using an ethical and transparent approach.

Laura highlighted a few guiding principles she uses on her own work at Chequeado. The most important one is to address conflicts of interest. All media organisations should ask think tanks to inform them about conflicts of interest. If the media asks that from all other governmental and public institutions, think tanks should also do it and be accountable to their specific audiences and also the general public.

Opening up the discussions around what think tanks do, who funds them and how, why have think tanks chosen a specific research agenda is crucial not only to ensure credibility and trust but also to be an active actor in the policy world and not merely reacting to complaints or situations where there are conflicts of interests or claims of lack of transparency.

Think tanks that are well established are more prone to be on the spotlight, but Laura notes that this applies to all think tanks. So it is important to have procedures and credibility systems in place to be prepared to inform about activities, funding, and current partnerships.

Laura also reminded us that collaboration between media and think tanks was always very important, but the pandemic has shown that it is even more important now, considering trust, credibility, and transparency. She briefly referred to the myriad of tools that help cooperation, decreasing linguistic and geographical distances. Laura reminded us that disinformation and bad information are going to continue to exist, so it is important to invest more money on education about critical thinking.

From the chatbox

Resources:

Fact-checking count tops 300 for the first time from Duke Reporters’ Lab

Signatories of IFCN code of principles

Questions:

If you have a conflict of interest and you mention it then how valid will the think tanks’ report be? Would our judgement be compromised based on this conflict of interest; and could this affect how the public then perceive the work and what the think tank publishes?

While transparency in funding seems like a clear ask, would you also ask think tanks to be more transparent in their ideology? Some think tanks claim to not have an agenda / political viewpoint. What do you think of this claim?

In your opinion, what is the best way to engage with a journalist or media house?

Watch the video to find out how Laura answered these questions.

Closing remarks with keynote listeners

Keynote listeners: Janis Emmanouilidis (European Policy Centre), G Gurucharan (Public Affairs Centre India), Sarah Lucas (Hewlett Foundation), Regine Wehner (Bosch Foundation)

Moderator: Enrique Mendizabal (On Think Tanks)

For the closing session, we decided on a different approach. We invited a set of keynote listeners from different regions to share their insights and thoughts about the keynote and parallel sessions. The discussion was also open to all participants in the event platform and OTT’s social media.

DAY 2

SESSIONS ORGANISED BY PARTNER ORGANISATIONS

Cracks in the knowledge system: whose knowledge counts and whose knowledge do we need?

hosted by INASP

Panelists: Prof Maha Bali (American University in Cairo), Dr. Joy Kiiru (Mawaso Institute and University of Nairobi)

Host: Jon Harle (INASP Director of Programmes), and Chalani Ranwala (Verité Research)

Key takeaways

John Harle from INASP framed the session stating that in the last nine months we have paid more attention to communities and how to transform the process of producing knowledge into a more inclusive one: where we are from, who we are, and what languages we speak either help or hinder us. These are not new problems, however the pandemic has exacerbated them. We have deeper questions: Whose ideas count? How are ideas valuable? How do they translate what gets funded- and what gets published?

Equity matters. However, this is often followed with a ‘but’. It matters, but there is a need to maintain quality and standards. It seems equity and excellence are opposite sides of the spectrum; and excellence is assigned by those who have the power, who control the knowledge. The focus on the capacity to produce and communicate is understood as a process of change and that is why we should listen and learn from others.

Maha Bali from the American University in Cairo gave several examples of how inequalities were exacerbated and others were inequality decreased during the pandemic.

An obvious benefit has been free online conferences, which are available to all those who have time and access to the internet. However, there is still a bigger presence from North than from the South.

Maha referred to the social justice model by Nancy Fraser: Who has the power to decide who gets to speak? How can technology change the way we interact with each other? Platforms are limiting and empowering. There are still barriers, for example, where authoritative governments can monitor even more and access more information.

Another important aspect are the resources needed. When talking about access, it is not just access to digital, but access to the language of technology and digital literacy.

Chalani Ranwala from Verité Research also highlighted the importance of access. Going digital means increasing access to knowledge that was not available before. For example, it is now easier to have more inclusive events. It is easier to have more variety in the voices heard.

Moving conversations online has opened the way to be more inclusive at a lower cost. However, moving information online might mean that some communities are not receiving the information in the correct way. There is a need to think how to reach out to all communities.

Joy Kiiru from Mawaso Institute and University of Nairobi also mentioned another important aspect: Africa cannot adapt to Europe’s restrictions to combat COVID-19. Realities are different, it is not possible to rely on knowledge created by other countries. How to create this knowledge?

What can be done practically to make learning and knowledge production more inclusive and equitable?

Maha pointed out that in Egypt, for those who had the resources, the move to digital was relatively straightforward. For those who do not have a support process the process was much more difficult. Another aspect is that people usually want to go directly to the tools, but don’t think about priorities, values and processes behind them. It is important to address the social needs of people.

Chalani highlighted the importance of language and how to overcome its barriers. In Sri Lanka, a trilingual language country, much of the academic knowledge is only in English, which is a huge restriction to reach different communities. Knowledge and research must be accessible in all languages, there should be an active effort to adapt and disseminate in local languages. Sharing knowledge should be packed in a way that many people can consume.

Joy stressed that bias can limit an individual, who might perform below their ability because of those perceptions. Research is funded from the outside, someone wants to dictate research, without appreciating the local knowledge and understanding context.

From the chatbox

Resources:

How research excellence is neo-colonial

Community-building resources for online

Questions and comments:

In this new normal how do we ensure community engagement amongst higher education institutions, when much of research work has shifted online?

How much of the communities we are engaging with are themselves able to communicate or collaborate online? Depending on what the field is, it may not be possible.

Your discussion on language made me think of a study with domestic workers done by Martha Farrell Foundation; wherein domestic workers themselves conducted the study in THEIR language in their community through a participatory approach. The study was very insightful because it was done BY the workers FOR the workers.

Given what Joy said about where the money comes from and how the agenda is decided, how do we break that? We, the Global South, don’t have the money and need money to do this critical work. So what to do? MNCs? Philanthropists? CSR?

It is possible to tackle inequality at global level (e. Access to research)? Countries in the Global South create their own, small self-sustaining, self-serving system? Thus national scholarly publishing systems become compartments, isolated from the global publishing system?

Watch the video to find out how the panel answered these questions.

Roundtable discussion: Narrative power & research

hosted by Oxfam and On Think Tanks

Speakers: Krizna Gomez (co-author of Be the Narrative) and Enrique Mendizabal (On Think Tanks)

Hosts: Caroline Cassidy (On Think Tanks) and Isabel Crabtree-Condor (Oxfam)

This session was inspired on Narrative Power and Collective Action (part 1 and part 2), a publication by Oxfam and On Think Tanks.

Key takeaways

Caroline Cassidy from On Think Tanks framed the session on the back of the publication, which features voices from across a range of sectors on what narrative change means to them, what can be done, and how we can take the conversation forward. Caroline then raised the question for the discussion: how can think tanks and research institutes get better at embedding this (narrative work), particularly at a time when we are facing really tough challenges in terms of social change and looking for positive outcomes. What is the role of research, researchers and think tanks in contributing to narrative change?

Isabel Crabtree-Condor from Oxfam shared that in her experience working on narratives she’s learned that narratives are not only in the purview of experts: we are all a part of it and are doing it daily through our work already. So, how can we do that more consciously? How can the knowledge that you have (as thinktankers) contribute to storytelling at scale on big issues or big ideas/ideals.

Contributing towards and amplifying new, inclusive, narratives is also one of the ways that we can collectively support positive change in society.

Isabel conducted all the interviews in the Narrative Power and Collective Change publication, and she found that the prevailing message from all those conversations is that narratives are a form of power. And narratives are so powerful because they act as activators: shortcuts, hidden code for our brain. We’re hard-wired for stories and the larger narratives that they feed into.

Narratives are powerful and dynamic, and they often lurk beneath the surface like deep ocean currents. This means they are a bit outside our sphere of influence, individually and collectively. The positive news, however, is that just as narratives are about power, power is also not static. This means that narratives can be reinforced, reshaped or challenged.

Enrique Mendizabal from On Think Tanks connected all this to think tanks, framing his reflections around three main ideas:

- Narratives are important for think tanks because they can affect the context in which they work. They can affect them and what they can do.

- Narrative development, change or protection of narratives is a strategy that think tanks can pursue.

- Narratives have important consequences on many people, often on very vulnerable people.

Think tanks often present themselves as being neutral. However, this is not true: nobody is neutral, especially when dealing with issues of public interest. This concept of neutrality might hold true when you look at their publications individually. But when you look at their arguments over a long period of time- arguments that individual researchers or organisations communicate, develop and share- you start to see these narratives emerging. These are filled with concepts around emotions, politics, ethics, interests, morals, beliefs, etc. And these are clearly not neutral.

Narratives have important real-life consequences. They can affect allocation of resources, they can mobilise people to protest, they can embolden and power repression, and many other behaviours at personal, organisational or institutional level. Think tanks working at national and regional level need to be conscious of the responsibility in how they use narratives.

Krizna Gomez from Be The Narrative reflected on her experience as a human rights lawyer working in a think and do tank.

In the world of social change and activists, there is not a lot of appreciation for the interaction between the world of evidence and research and analytical work, with the work of narrative building. This is a missed opportunity. Narrative work should be approached in a multi-disciplinary way.

The work that think tanks do can really contribute to narrative change:

- Where there is an overwhelming phenomenon that is being experienced by social change activists, think tanks can provide the analytical framework by which to construct narratives.

- Providing evidence: there is a lot of talk about evidence-based social change communications. This is not really obvious to a lot of activists who operate on assumptions vs the study of audiences, testing of strategies, etc. There is no evidence before, during or to test narratives.

- Providing activists skills to gather that evidence themselves.

Aidan Muller from Cast from Clay contributed to the discussion from their experience working with different audiences and the perception of the public on experts. They see that a lot of countries are no longer valuing the input of evidence or policy experts and expertise.

When such a big part of the population is no longer engaged with evidence-based policy we need to be asking questions of ourselves and how we let it get to this point.

Narratives are not neutral- they have a direction of travel. If we want to change narratives everyone has to point in the right direction, and eventually the direction of travel will change.

Thomas Coombes from Hope Based Comms contributed to the discussion from his experience working in human rights.

We have to accept that we are never neutral in what we produce. Knowledge is power and the people who produce knowledge create power because their perspective becomes what is truth. Narratives can be so powerful that the sense of what’s common sense can be used to dismiss bold ideas for change.

Considering this, think tanks need to be honest and open about the values they’re trying to promote when they do their work, rather than claiming to be neutral arbitrariness of truth. Progressive values like kindness, empathy, compassion, and shared humanity are things that right now feel kind of naïve and soft. It feels hard to put them into the political space on the same platform as security or economic growth. But neuroscience and anthropology have shown that this is how humans operate. Think tanks can bring together these values to have more policy thinking based on the reality of how human beings operate.

Laura Hankin from Rodeemos Diálogo shared her perspective as a researcher, offering more questions to think about, and considering that one valuable element of research and researchers is their role as a critical friend asking those critical questions around ethics.

Narratives are about framing how we see the world, and we can’t be doing from looking solely from the outside: we need to put it as a conversation between everyone.

Narratives involve emotions and come from feelings. Changing narratives is about how we tap into emotions and feelings, not only to change them but also to recognise and value them- not dismissing narratives but recognising where they come from.

From the chatbox

Resources:

Change is all about narrative, by Caroline Cassidy

Changing Our Narrative about Narrative: The Infrastructure Required for Building Narrative Power

Twitter chat: Narrative Power and Collective Action

On public engagement, by Enrique Mendizabal

Instead of shrinking space, let’s talk about humanity’s shared future, by Thomas Coombes

Framing the Economy: How to win the case for a better system…

Questions and comments:

Narratives are…

- Narratives are the stories we believe to be true, and are often shy of challenging.

- How we make ideas stick, how we can effectively transmit expertise and ideas to the wider public domain.

- The stories and ideas we tell ourselves and others about how the world is or how it should be.

- Stories that help make sense of, understand, and connect different aspects of an issue?

- The most powerful narratives are rooted in values.

- Narratives and stories make institutions more human, give them reasons to exist and see their work, and engage and connect with their publics. And everyone loves stories…part of human nature to understand the world.

- Narratives are big, overarching stories through which we make sense of the world.

- Stories that help us make sense of world around us and our community. They produce change by building ‘we’, ‘them’ and the rest.

- A way of framing how we see the world and interact with others.

- Important for all the reasons above, and because if we don’t establish our own compelling narratives, others will!

- The frameworks which help us understand the world.

- Important to convey complex information into simple language/method for all types of stakeholders to understand and make decisions. As a communicator, I attempt to use this tool often.

Do you think that, beyond providing analysis, evidence & skills, think tanks should also be engaging more (consciously) in strategic communications and narrative change in their own communications? Or is that a slippery slope and better left to advocacy organisations and activists?

Think tanks often have to work in short term project cycles, I also think that we can get better at recognising when larger advocacy movements or organisations are a target audience for the research and getting our evidence to them to use, as well as recognising when policymakers are the target audience and we want to try and affect change directly. Sometimes it may be both.

Should think tanks engage in narratives? Absolutely. ESPECIALLY think tanks. If think tanks did not engage in narratives, it reinforces the narrative of knowledge as the exclusive remit of elite circles, which include think tanks. Knowledge (and facts) become dismissed by the public as irrelevant or distant to their daily lives, and thus unimportant in governance and public policy.

1) its not just the right that exploits narratives, 2) narratives have long-term consequences – far beyond an individual recommendation (in fact a narrative can prevent us from looking for mistakes in our plans), and 3) they should not be seen as one more tool in the toolbox – far more important.

We also need to improve the narrative playing field with alternatives. With the sorry state of our ability to debate or have a dialogue about many important issues in society, it’s important to not just bash opposing views but listen and offer alternatives.

Watch the video to find out how the panel answered these questions.

Think tank ecosystems: characteristics, functions, and implications

hosted by the OTT Research team

Presenters: Silvia Menegazzi, PhD (Adjunct Professor International Relations, LUISS Guido Carli University), Dr. Bert Fraussen and Dr. Valérie Pattyn (Faculty of Governance and Global Affairs, Leiden University)

Moderator: Andrea Baertl (On Think Tanks)

The recording of this session is not available.

Key takeaways:

This session explored studies of two different think tank ecosystems: Belgium and China to better understand how the context shapes the work of think tanks.

The first discussants, Dr. Bert Fraussen and Dr. Valerie Pattyn presented preliminary findings of a study they carried out in Belgium.

For their study, the authors conducted a mapping of think tanks, a survey with 15 think tank representatives and three interviews with think tank directors with a focus on domestic oriented organisations (excluding the many European-oriented ones operating in Brussels). They found three important features in the ways domestic think tanks approach issues:

- Time considerations: the think tanks interviewed have a long-term view, they try to formulate long-term sustainable policy solutions.

- Evidence based nature of policy advice: respondents emphasised that there is no lack of knowledge (there are already plenty of studies addressing societal issues), but what is missing is the right “translation” of this knowledge into more digestible products for policymakers, which is what think tanks can do.

- Consensus-oriented mode of operating: think tanks bring together many stakeholders to have different perspectives and to increase the legitimacy of their work. This consensual style is seen across the ideological spectrum, as very diverse think tanks try to involve stakeholders with different positions and interests in political debates.

A key difference between domestic think tanks and those more EU-oriented is that EU-oriented think tanks have much more competition. Belgian domestic think tanks are small and some are relatively new, but there are tens of large think tanks focusing on EU-politics, so it’s a very different landscape.

The second presenter, Dr. Silvia Menegazzi, discussed a paper on how Chinese think tanks are playing a bigger role in public diplomacy. She argues that this idea of the role of think tanks in authoritarian contexts is often underestimated because the Western literature, for many years, took for granted a ‘fixed’ definition of think tank. 2012 was a critical juncture for Chinese think tanks because the Xi Jinping administration recognised officially the role of think tanks. This strategy established by the Chinese government has led to a boom of think tanks, which have then been used as instrumental actors for increased international exchanges.

Chinese think tanks contribute to the policymaking process, especially on issues on which the government needs expertise and uses think tanks for consultancy services. Nonetheless, we have to understand that think tanks in China are not fully independent from the government and it is more likely that they provide expert knowledge than that they can change specific policies.

From the chatbox

Resources:

Political knowledge regimes and policy change in Chile and Uruguay

Chinese Think Tanks and Public Diplomacy in the Xi Jinping Era, Global Society, 2020

Questions:

I know you excluded the Brussels EU-oriented think tanks from your analysis, but do you think that the Brussels context would be very different? Particularly, I thought the ‘anticipatory’ nature you found was very interesting and I wonder why this would be and if it would be very different from the EU-oriented think tanks.

How important is the ideological position for think tanks in the crowded landscape? Does ideological position help them to stand out among others?

What are the other policy advisory actors in the Belgium landscape?

Do these think tanks also emphasise their independence, as think tanks tend to do in many other countries? Or how do they present themselves to other countries?

Data Detox Kit: misinformation and disinformation

hosted by Tactical Tech

Moderator: Louise Hisayasu (Tactical Tech)

Key takeaways

Louise Hisayasu led participants through a workshop on disinformation and misinformation.

Why is information so complicated? The internet has really changed the way we consume information- there is much info available to us, and the way that we consume information has changed due to social media and the 24-hour news cycle

Humans are emotional creatures so we have an emotional connection to information. Our brains are constantly processing information and making decisions on what to believe and what to leave on the side, and we all have different motivations and perspectives to share different things.

What leads to information disorder?

- Continued influence effect: what happens when we still believe the info we’ve been given even when it’s been proved wrong to us.

- Illusory truth effect: repeated information is more likely to be judged true than novel info bc it has become more familiar

The term fake news is misleading. It is often used as a way of discrediting information, but there is a grey area between what’s true and what’s false. This is why it’s important to understand the terminology:

- Disinformation is information that is intentionally false and designed to cause harm

- Misinformation is information that is false, but spread without the intention of causing harm

Louise then led participants through three games:

- Misinformation or disinformation challenges

- Become an investigator game: identify which capital city images were taken, and what clues are there to identify these

- Social media analysis to see if the information is true or false (using reserve image search)

Finally, Louise shared four tips on sharing with care:

- Recognise your emotions and remember that we respond to information emotionally

- Dig a little deeper, don’t take all information at face value and ask critical questions: why am I seeing this, who’s behind it?

- Talk to people, everyone is vulnerable to sharing misleading information. Try understanding and use non-judgemental language

- Debunk: provide a clear explanation of why that information is false and what is true

Resources:

The era of the think tank: An analysis of the German think tank landscape in foreign and security policy

hosted by Robert Bosch Stiftung

Speakers: Annalena Rehkämper (Phineo) and Enrique Mendizabal (On Think Tanks)

Moderator: Verena Heinzel (Robert Bosch Stiftung)

Key takeaways

Annalena Rehkämper from Phieo presented a mapping of German foreign policy think tanks which clearly identifies different think tank families – possibly created over a series of waves throughout Germany’s history – with the largest growth since the 1990s.

The mapping identified at least four types of think tanks based on their main way of working:

- Academic think tanks

- Policy institutes

- Activist/do tanks

- Transnational think tanks

Each one presents differences in key categories of think tanks’ work:

- Proximity to politics- for instance, academic think tanks are removed from politics while policy institutes are very close.

- Funding – academic think tanks’ funding is largely public while private institutes’ funding is largely private.

- Outreach – rather low for academic think tanks and more public with policy institutes.

- Digitalisation – poorly developed with some exceptions for academic think tanks.

- Internationalisation – very low, through gatekeepers and northern led partnerships or southern led networks.

The review also found important weaknesses or challenges that should be addressed to strengthen the German foreign policy think tank community. Among them:

- Lack of practical relevance in their research

- Organisational deficits

- Weaknesses in their outputs

- A tendency for uniformity and insufficient controversy

Funders were also considered in the analysis, and it was concluded that they:

- Suffered of ‘projectitis’

- Did not offer venture capital to promote innovation

- Lacked of clarity in their own missions

Enrique Mendizabal from On Think Tanks, in commenting the report, considered that this analysis chimed well with cases from around the world. All in all, many of these challenges are experienced by think tanks in other contexts – both in the Global North and the Global South and even in what may be perceived as very developed think tank environments.

He recommended that this kind of analysis should be done, systematically, at the national level.

You can see the slides presentation here.

From the chatbox

Resources:

OTT series on the definition of think tanks

Questions:

@Annalena: how effective was the feedback/recommendations. Was it well received ?

What would you say are the practical implications for think tank communications in Germany from this?

Your report focuses on foreign and security policy. Can you briefly talk about other types of issues? I’ve noticed that German think tanks seem to have a real strength on climate change for example. Do you think the same findings would apply?

Watch the video to find out how the panel answered these questions.

Defining a think tank model of storytelling

hosted by Cast from Clay

Speakers: Aidan Muller and Katy Murray (Cast from Clay), Lizzie Harvey (Theos think tank)

Key takeaways

This session builds on two slides that Cast from Clay presented two years ago, considering more recent conversations around narratives and storytelling.

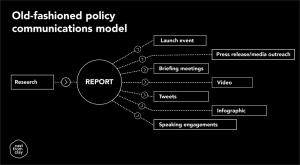

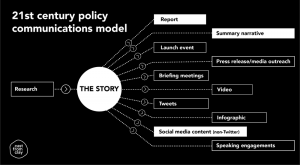

The slides show the standard model of think tank communications (with the report at the heart of all communications activity and a number of activations that follow) and the 21st century policy communications model, which focused on the story rather than the report (seeing the report as one more communication asset).

How to start to define a framework for storytelling?

- Embrace the new policy dynamic. Up to 10 or 15 years ago policy experts only really had to focus on policymakers and mainstream media. These set the policy agenda, and the public remained a passive actor. This changed with social media, which gave the public a voice. It’s messy, but it’s quite a powerful force. This shifted from a bi-power dynamic to a tri-power dynamic where commentary and opinion are as valid as news, and emotions are just as valid as facts. What policymakers want from academics and experts are frameworks to help them understand the complex world that they live in and put simply, they want the stories.

- Take people as they are rather than as we want them to be. People are more likely to remember stories than they are facts. This is about the role that facts play within the wider practice of storytelling. One of the main findings of cognitive science is that people think in terms of frames and metaphors. So, when the facts don’t fit frames, the frames are kept but the facts are ignored. This is a challenge for all of us who believe in facts and evidence, particularly in policymaking.

Use storytelling to tap into the human.

- A think tank model of storytelling. What’s the difference between stories and narratives? Stories are the things that happen to people, narratives are shaped by a collection of stories. Narratives occur at personal level, at community level, and they also occur at societal level. Crucially, narratives have a direction of travel, and they work as a curating filter. When stories don’t fit within a narrative, they are simply filtered out. This is why narrative change is so hard to achieve.

Storytelling exists as two levels for think tanks:

- The message: where your research exists, the human story behind the data

- The environment: this is where the narrative plays in. What does your world look like?

Is this outside the remit of think tanks? Cast from Clay asked 100 members of the UK parliament what they thought the role of a think tank should be today:

- One in three of them said that think tanks do enough to explain policy ideas to the public

- Over half of them thought that think tanks need to do more and have a duty beyond publishing reports to articulate their vision of society.

Aidan then presented a framework for storytelling for think tanks.

Lizzie Harvey, from Theos think tank, talked about their work around enriching the conversation and belief in society, believing there is untapped wisdom in faith traditions that can speak into some of the big questions about how we live well today.

The prevailing narrative around faith and believe is not always a positive one, so this requires a certain level of environmental storytelling.

Lizzie shared four case studies:

- ‘The sacred podcast’: set out to find a way to find more productive, less combative ways to think about our divides. This related to stortytelling because they started to tell a different story around faith and believe

- ‘Forgive us our debts’: a report which looked to tell the human story of debt.

- ‘Growing good’: a report that is about promoting social action through churches by telling the human stories.

- ‘Religion and worldviews report’: religious education in schools is outdated and there has to be a better way to think about faith and belief.

Lizzie then shared the experience of Theos think tank in growing their comms team and the balance between researchers and communicators.

From the chatbox

Resources

Democracy 2.0: a new role for the policy expert?

Why think tanks should employ fewer researchers, by Louise Ball

The Perils of Perception: Why We’re Wrong About Nearly Everything, by Bobby Duffy

Don’t Think of an Elephant! Know Your Values and Frame the Debate: The Essential Guide for Progressives, by George Lakoff

Secrets of digital content for policy engagement

hosted by Soapbox

Speakers: Jennifer Trent Staves (Wellcome Trust), Paul Franz (CSIS iDeas Lab), Clair Grant-Salmon (IIED)

Host: John Schwartz (Soapbox)

Key takeaways

This session focused on how not to produce content in the same old way but rather investing in producing content regularly, in a relevant way and addressing areas that are your expertise and telling stories.

Jennifer Staves started by disclosing the mysteries of how to approach content through storytelling. The important aspect is to understand digital channels as people’s experiences of the organisation, not only a tool.

Jennifer gave the example of the Wellcome Collection in which the whole editorial process was changed moving away from a blog towards a magazine storytelling approach. This approach led to more content on a regular basis: more people read the content, more people read for longer, fewer people left without interacting, and other organisations advertised the stories driving traffic to the website. The key was building a regular cadence and making sure it fit.

The best is to test ideas, and decide what success looks like, and how to start building a relationship.

Important things to remember:

- Operationalisation is key.

- Be consistent and start small.

- Think programmatically.

- Publish regularly.

- Create guidelines that help you make good content.

- Be transparent, and track performance.

Paul Franz imparted a formula for engaging with research and creating content around mapping. He highlighted that the attention deficit has been talked about for a long time as the main challenge for communications, but it is actually more about attention getting. Think tanks usually focus on a repository of all research that was done without thinking about the most effective ways of reaching audiences.

Paul gave the example of CSIS that addressed that issue focusing on expanding the use of satellite images together with mapping to illustrate pressing issues. The objective was to create stories, not repositories of information. Having endless streams of data and information, and using it to create stories and narratives through academic reports, but also using videos aimed at making the data more publicly accessible.

What has been the output? Influencing and engaging in political conversations.

Clair Grant-Salmon talked about how to put digital content to the right audiences focusing on marketing, digital, and data.

Clair recommends that when talking about building digital profiles for effective engagement, the focus should be on a unique combination of audiences, objectives, and the content you are generating which creates a unique digital identity.

This should be process driven:

- Put audiences at the heart of what we do – building relationships to understand them and the nuances

- Choose the right channels and messages to get out there

- Use data to see what is working and what is is not working and improve the process

It is important to do an audience profiling, adding personality to their audience. Where did they find information? How are they seeking information when they want to make decisions? What decisions do they make? How much time do they have to consume information? Hit audiences in different ways with the same message to reinforce identity and brand. Evaluate the options with data using scenario mapping and journey mapping to understand the needs and intentions of the users.

There is no need to throw everything to the same channel. It is important to focus on what organisations are trying to achieve and find the right space for that.

From the chatbox

Resources:

The story behind stories and our journalistic approach

A practical guide for making a journalistic approach to digital content

Dataset on chemical weapons use in Syria

Questions and comments:In John’s intro he alluded to a modern looking website with old school content. To my mind this doesn’t just require a refresh of the communications/engagement teams. It requires: leadership commitment, changes in the way the research team works (what issues they look into, the methods they use, the outputs they produce -e.g. what Cast from Clay talked about in the last session, the skills required from the researchers), funding/fundraising, etc.

Mapping really works for the CSIS brand. Are there particular types of content that work really well for the brands of think tanks represented in the audience?

I think often researchers/think tanks make assumptions about their audiences based on past experience or on a few visible representatives of their audiences. Do you compare what your researchers say with what the real audiences say about themselves?

Any suggestions to keeping appetite alive for promoting work on ‘traditional’ channels such as websites? We notice now more and more people are keen to resort to social media promotion only for the ease of getting the message out there quickly to the detriment of a website which often is the main entry channel to the organisation’s work.

(On academic researchers) I’d say that’s where getting in at the proposal stage comes in too, not just making sure there’s budget but getting in those important questions about what it is you’re trying to do, why it’s important and who you need to reach.

Watch the video to find out how the panel answered these questions.

Previous

Previous