Free-riding among funders is more common than you’d expect. It can have a negative effect on the willingness of potential donors to engage with a think tank in the long term. It can also make life very complicated for think tanks and difficult to fulfil their missions.

The call for more adequate funding and pricing has been gaining momentum in the last years. Now, a group of US funders have come together to call for a new approach to fun thing charities: Pay-What-It Takes Philanthropy. In practice:

a flexible approach grounded in real costs that would replace the rigid 15 percent cap on overhead reimbursement followed by most major foundations

Free-riding

Free-riding among funders could be described in the following way:

- Funder A funds think tank X to produce a study -it could be a study the think tank wants to do or one commissioned by the funder;

- However, the funder refuses to pay for anything that is not directly linked to the production of the study. It makes the point of not accepting a bill that includes an organisation overhead charge;

- Still, it expects the study to be published, presented, shared, and communicated; and

- It wants the organisation to provide financial and completion reports as a condition to receive final payment.

The problem with this is that to carryout a study (even a desk based study as a literature review) think tanks have to make investments and incur in indirect costs, such as:

- Office and administration;

- Subscriptions to journals or databases;

- Proposal development and fundraising;

- Project management and accounting services;

- Microsoft Office and other software;

- Training for existing and new staff;

- Administrative, legal and financial costs related to subcontracting (which is often what think tanks need to do in larger and multi-country studies);

- Communication costs; etc.

Why does this happen?

There are many reasons for this, of course. I have come across a number of explanations which include funders seeking value for money outputs, others are limited by legal or statutory constraints, and others are simply actively trying to take advantage of other funders’ efforts.

Not all do this for the same reasons (based on cases I have witnessed):

- A consultancy or think tank acting as a project lead and subcontracting another think tank treats it as a service provider and needs to keep its costs as low as possible -it will try to avoid paying for anything not directly related to the study;

- A public funder is concerned about the think tank’s wage bill hence only wants to pay for communication activities -just in case the aid-sceptic press gets a hold of that wage bill; or

- A funder is bound by law or statute to pay fees within a pay-braked and will make no distinction on location or complexity of the project.

What is the problem with this?

When funders do not pay the real costs of policy research (including management, communications and research) they set out a chain of reaction that leads, often, to a never ending vicious-cycle:

- Unable to cover central costs through the fair contributions of projects (for instance, through overheads), think tanks have to resort to a few core/institutional funders -and must therefore cater for all their demands;

- Think tanks and researchers may be driven to seek-out more and more projects to attempt to make up the necessary funds in opportunistic budget loopholes or by including the “token admin or comms” here and there -inevitably, this means more administrative demands which are not necessarily covered by overhead or core funds and hence researchers need to seek out more and more projects;

- Unable to afford appropriate central services think tanks resort to cutting corners (hiring cheap, buying below-par support, pass on staff development opportunities, etc.) which dents their capacity to carryout high quality research in the long run and reduces their ability to command enough funding to keep afloat; or

- Are left having to depend on larger (often northern based) organisations to bid and win large research projects as they cannot invest the necessary time and resources necessary to develop competitive proposals or bids -inevitably, they are then tasked with producing the country case study of a far more interesting (and more profitable) project; etc.

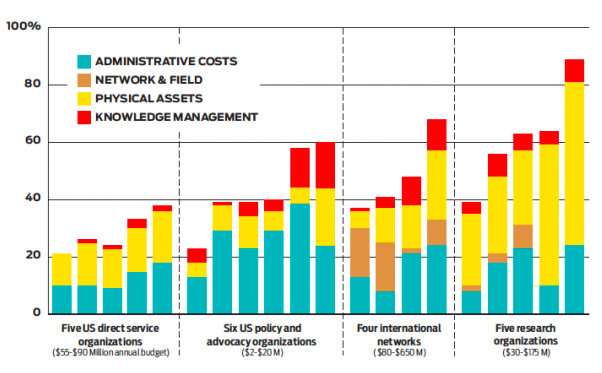

A study by The Bridgespan Group in the US found that indirect costs can account for anything between 21% to 89% of direct costs. In the graph below, organisations that could be associated to the think tank label report indirect costs that are as high as 60% and research organisations as much as 89%:

But this has other consequences, too. Project only funding does not lawyer foster productive relationships between funders and think tanks. Goran Buldioski argues that:

Donors who award core and institutional grants, unlike their peers who underwrite projects, have a fuller picture of the organizations they support.

This may or may not matter in the short term but can explain some less than fair contractual practices that weaken think tanks in many cases.

Underfunding also fuels a a shadow economy in which funders and think tanks see to compensate or make up for what is not being paid over the table and this means that it is imposible to know how much things really cost. eri Eckhart-Queenan, Michael Etzel, and Sridhar Prasad argue that:

funders and grantees purposely obscure financial data and quietly craft end runs around the arbitrary indirect cost spending caps imposed by most foundations. Foundation program officers, for example, often team up with grantees to recategorize underfunded indirect costs as direct costs that the funder covers. Other times, funders approve capacity-building or general operating grants to close the indirect cost gap. As a result, we do not know as a sector what it really costs to achieve impact.

Pay-What-It-Takes Philanthropy

The new approach, spearheaded by the Ford Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Weingart Foundation, and other who have joined the Real Cost Project initiative, raised a number of challenges for both funders and think tanks (and grantees in general):

- More transparency: think tanks who want more core funding or adequate-priced funding will have to be more transparent about their business and funding models. They will also have to be open to recommendations and suggestions from funders on how to improve them.

- A focus on quality: recognising that good ideas do not come cheap funders will have to pay greater attention to the ideas and less to the value for money of the input-output proposition.

- Investing in relationships: both funders and think tanks will necessarily have to invest in a strong relationship with each other. A relationship in which the grantee is not a passive receiver but an active player in the funder’s own policies.

- A new kind of support: we have argued before that funders (especially core funders) should provide their grantees with support to negotiate better contracts with their project-only funders.

- Better financial management: think tanks will have to invest in their capacity to manage their funds more effectively including being able to adequately price their work. If funders are going to pay for direct and indirect costs then they will expect the grantees to be able to account for these correctly. Few may have the necessary tools (e.g. timesheets, budget tracking, etc.) to do so.