[Editor’s note: This blog series has been purposefully adapted for On Think Tanks from a working paper Gerard Ralphs developed as the 2011 Research Awardee in the Donor Partnerships Division at Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC). The original paper was compiled as a think piece for participants attending the IDRC’s Resource Mobilisation for Research programme workshops in Ghana, Senegal, and Kenya, hosted in collaboration with the Think Tank Initiative (TTI) targeting think tank leaders. The views expressed in this series are solely those of the author, and do not represent the views of IDRC, TTI, or IDRC’s donor partners.]

The first part of this blog series deals with a set of conceptual questions: What is a business model? What is a think tank business model? How is the concept of a business model distinct from that of a funding model?

In this second part, I continue the exploration of the conceptual terrain, this time by developing a series of points about the ‘type’ of organisation that a think tank represents along a spectrum of organisations.

The suggestion here is that if there is greater clarity about the core function of a think tank in relation to other organisations in research and policy ecosystems, then think tank business models can be much more clearly defined (and refined) by organisational leaders. To provide an additional layer of context this suggestion, I provide three illustrative examples.

I also set out some questions to guide future research.

An organisational typology

Organisations are often classified through the lens of their legal status—ie for-profit, for-profit, quasi-government, and so on.

But the concept of organisation type, insofar as think tanks are concerned, can be understood differently; that is, in terms of a typology of knowledge and political organisations.

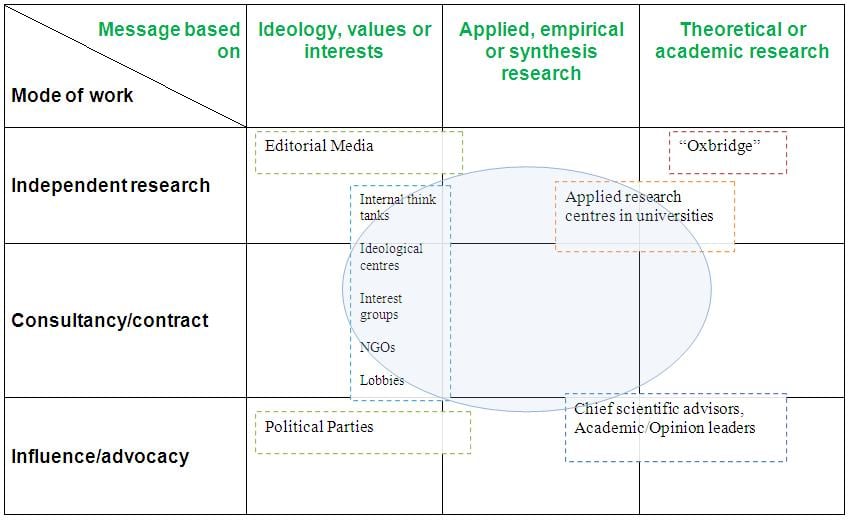

Source: Enrique Mendizabal (2010)

As shown in the figure, a number of types of research/advocacy organisation exist with different degrees of emphasis and concentrations of focus.

In one corner of the research and policy organisation landscape, as it were, lie university disciplinary sections that conduct pure, basic and/or blue skies research (so-called “Oxbridge”).

At another end of this landscape, lie political parties, whose time horizons and policy agendas are determined principally by voters and voting cycles.

It is generally accepted that think tanks straddle research and policy ‘worlds’ (light blue circle in the figure).

A particular think tank’s position on the organisational spectrum can also provide hints as to the modes of work, types of funding, and networking imperatives that may need to be discovered in order to achieve organisational objectives.

As Kevin C. Urama of the African Technology Policy Studies Network has been quoted as saying:

It is a challenge to influence policy if you don’t have a proper platform. If you have good science outputs but are not entrenched in the political processes your science will not see the light of day.

Running a think tank effectively compels leaders to constantly be inward-looking (ie toward its organisational design) as well as outward-looking (ie toward the changing needs of its stakeholder communities).

It is important, too, that leaders understand the relationship between a think tank’s activities and the regulatory regimes and legal status of the organisation in a particular country context.

Governments typically set down the rules for and legal status of organisations. And tax regimes and labour laws add further determining criteria, which can fundamentally shape how think tanks approach their operations. +

Staying unique

What follows from the discussion above is that just about every policy research organisation/think tank has and, by definition, requires a unique business model: South African think tanks tackle different issues, in sometimes similar and/or different ways, and from a particular support base, than their counterparts in the UK or in Southeast Asia.

So think tank business models must also show agility and adaptability to changing needs and circumstances, both internally and externally.

Early African think tanks—for example, the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) or the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC)—are radically different organisations today. This change has come about no doubt because of national, regional and global political and economic developments, but also as a consequence of new ideas and modalities within research and funding communities.

Thus, while lessons on ‘good business models’ can and should be drawn from Africa’s longest standing think tanks, each think tank’s business model will vary from those of its counterparts. And as a consequence a think tank must continuously evaluate and evolve its business model. +

Illustrative examples from Africa

Building on the previous sections of this blog, I attempt to briefly describe and analyse the business models of three think tanks based in Nigeria, Tanzania and South Africa.

The description and analysis, developed in 2011, is neither in-depth nor comprehensive. Rather, its purpose in the context of this blog series is to provide a set of illustrative examples that draw in some of the analytical/conceptual tools discussed in the first part of this series.

The ‘take-home’ argument is this: The scope for further research is large. A lot of questions are unanswered: What makes think tank business models successful over different time horizons? To what extent do think tankers consciously develop their business models? What is the utility of the concept of ‘business models’ for policy research institutes?

Brief description and analysis of three African think tanks’ business models

| Institute for Public Policy Analysis (Nigeria) | Research on Poverty Alleviation (Tanzania) | Centre for Policy Studies (South Africa) | |

| Short description | Independent policy research institute focussed on the principles of a free and open society, in Nigeria, across Africa. | Independent policy research institute focussed on social and economic research in Tanzania and Zanzibar. | Independent policy research institute focussed on democracy and governance, in South Africa, across Africa. |

| Institutional development | Founded 2002 as non-partisan policy research institute. | Founded 1995 as non-governmental civil society organisation. | Established 1987 as part of University of Witwatersrand’s business school. In 1992, transferred to a project of the Human Sciences Research Council (begins to operate from own premises). Restructured in 1995 as autonomous legal entity. |

| Legal status | Non-profit organisation | Non-profit organisation | Non-profit organisation |

| Governance | Board of Advisors (local and international) | Board of Advisors; Technical Advisory Committee | Board of Directors (local only) |

| Funding sources | Private companies; Individual donors | Governments; International organisations | Private companies; Individual donors; International organisations; Local organisations |

| Value proposition | Knowledge and policy engagement through:

|

Knowledge and policy engagement through:

|

Knowledge and policy engagement through:

|

| Business model description and analysis | IPPA is a standalone think tank without a larger institutional positioning. Its current business model is made up of diverse research and advocacy projects in the areas of health, entrepreneurship, and education. Some of these projects involve partnerships with other organisations. IPPA is financially sustained through a combination of individual, private company, and foundation support. Its decision not to accept funding from the Nigerian government, or its agencies, places it in a position that compels it to mobilise resources through alternative channels. | REPOA is a think tank that exists independently or a larger institutional structure. Its current business model of research and capacity building is afforded and sustained through grants from international organisation donors and governments that feed into its endowment fund. The five year strategy of REPOA (2010-2014) provides an indication that is has how the resources the organisation has at its disposal will enable it to achieve its mission. | CPS moved from having been embedded and supported within the larger institutional structures of a university and research council to being an independent organisation. Its current business model is made up of short and longer-term projects, yielding research and policy engagement results on governance and democracy related issues. These results are recognised by the respective research and policy communities in South Africa. This value-adding research-to-policy output is supported by private individual donors, local organisations and networks, and, to a lesser extent, private companies and international organisations. CPS is presently undertaking a strategic review based on the impacts of global financial recessionary pressures and shifting stakeholder needs and demands. This necessitates that CPS considers the viability of its business model. |

Implications for leaders

A whole range of key issues and related questions arise for think tank leaders from the preceding conceptual discussions and these examples. These concern the following:

- Institutional location: Should a think tank be housed within a government department, at a university, independently, or in some hybridised form encompassing a number of institutional locations?

- Staff make-up: Should a think tank employ more subject experts than experts with policy experience or communicators with policy and research experience?

- Research resources: What datasets or scholarly resources should a think tank invest in in order to ensure its research capabilities appropriately geared?

- Communication tools and channels: How do think tanks leaders ensure key messages research target audiences on a consistent and measurable basis?

- Oversight and strategic positioning: What management and board-level regimes should be set in place to ensure think tanks adhere to regulatory or sectoral requirements and are appropriately positioned for growth and/or organisational development?

Summing it up…

The political, intellectual, and operational contexts result in unique constraints and opportunities for think tanks. This also means that each and every think tank’s business model will be at once unique and particular to its internal capabilities and urgencies in its external environment(s). Because of this, think tank leaders need to consider their business models carefully and as a consistent strategic issue.

On the side of theory, a range of conceptual tools exist from management thought and organisational development literatures that can help think tank leaders to analyses, refine, and enhance their business models, and to focus their efforts on mission-achieving and sustainable research-to-policy activities.