Depending on your perspective, think tanks either enrich the democratic space by conducting policy research and facilitating public dialogue and debate, or undermine democracy by pushing policies favoured by powerful corporate interests. Till Bruckner explains how Transparify are contributing to debate about think tanks’ role in evidence-based policymaking by assessing their levels of financial transparency. The Transparify report, released this past February, enables citizens, researchers, journalists, and decision-makers to distinguish between legitimate policy voices and questionable sources of ‘expertise’. This post was originally posted on the LSE Impact Blog.

When prominent American politician Jim DeMint was asked why he gave up his seat in the Senate to become president of the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank in Washington DC, he replied that the new job would give him greater influence on politics and policymaking than his elected office had.

But is that influence benign or malign? Observers are divided. Professor James McGann, author of numerous books on the subject, argues that think tanks enrich the democratic space by conducting policy research, developing policy options, facilitating dialogue between diverse stakeholder groups, and stimulating public debates, regardless of whether they pursue an ideological agenda. More think tanks are better for democracy, he concludes.

In contrast, George Monbiot, a left-wing British commentator whose columns often lament the influence of think tanks, sees these organisations (or at least those whose politics he disagrees with) primarily as lobbying groups in disguise that undermine democracy by pushing policies favoured by the powerful corporate interests who bankroll them. “A few billion dollars spent on persuasion buys you all the politics you want,” he recently wrote. In a donor-driven marketplace of ideas, Monbiot warns, the think tank sector as a whole only serves to further tilt the playing field in favour of the rich.

Transparify, an initiative I work with, decided to contribute to the ongoing debate about think tanks’ role in evidence-based policymaking and democratic politics by assessing think tanks’ level of financial transparency. As On Think Tanks founder Enrique Mendizabal has argued:

Think tanks are all about influence. They are not, as much as they pretend to be, neutral ivory towers that undertake entirely value-free research and offer value-free advice… Think tanks help their case by presenting themselves as neutral academics… Domestic or foreign [funders], nobody hands over money to think tanks without wanting anything in return…. They all want something.

We decided to examine which think tanks voluntarily disclose who funds their work. Think tanks that lack confidence in their ability to maintain independence despite the ubiquitous donor pressures noted by Mendizabal are likely to feel defensive. They may keep their books closed in order to avoid awkward questions about why, say, their studies funded by Philip Morris always conclude that raising taxes on cigarettes is a bad idea, or why their institution only started to advocate for clean energy after it received a large grant from a solar panel manufacturer. Conversely, a policy research institute that has confidence in the quality, intellectual independence and integrity of its research and advocacy will have no problems disclosing its donors, no matter who those donors are.

The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) is an interesting case in point. In December 2016, leaked documents revealed that the London-based think tank had signed a multi-year funding contract worth at least £25 million with the Persian Gulf monarchy of Bahrain. The documents also revealed both sides had pledged to keep most of the donations secret. After the document had been leaked to the media, the IISS issued a statement claiming that it did “not accept any funding that may impinge on our intellectual and political independence”. But if the IISS leadership was so confident about its ability to resist donor pressures, why did it try to keep the Bahraini cash infusion – which may amount to nearly half of its overall funding – secret in the first place?

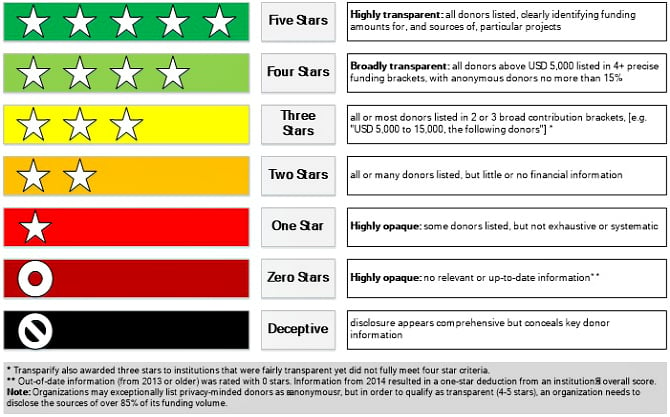

In order to measure differences in transparency, Transparify has developed a five-star rating system to allow us to compare think tanks’ disclosure levels across multiple institutions. The maximum five-star score shows that a think tank is highly transparent, revealing not only the names of its donors, but also how much each donor gave and the purpose of each donation. At the opposite end of the scale, an organisation with a zero-star rating keeps the identities of all of its donors secret. Below even this are those categorised as ‘deceptive’, which seem to disclose significant amounts of information but in reality hide major, potentially embarrassing donors from public view.

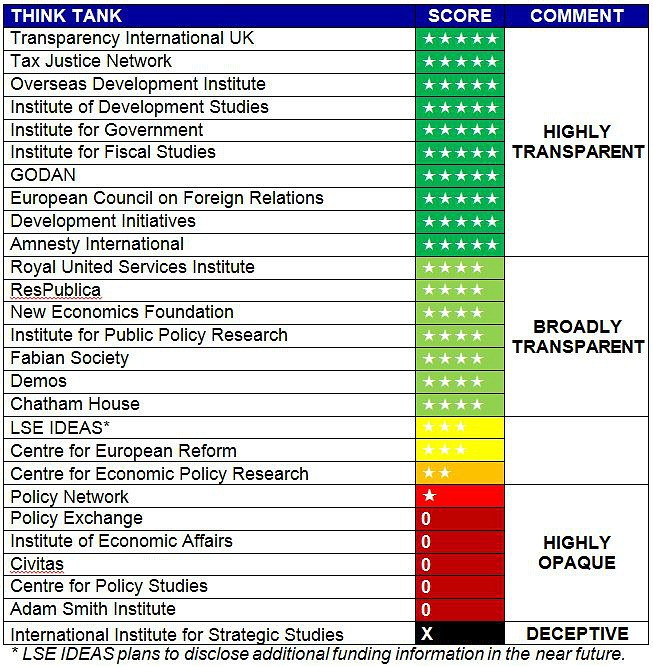

Using this system, we visited the websites of 27 British think tanks to assess their transparency (more information about the methodology is available on the Transparify website and also as an appendix to its report). This is what we found:

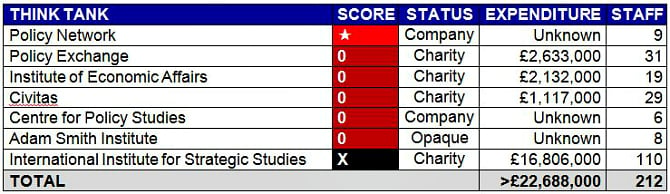

A closer look at the highly opaque institutions on our list confirmed our hypothesis that think tanks that hide their donors usually have something to hide. For example, according to research compiled by TobaccoTactics, the Adam Smith Institute, the Centre for Policy Studies, and the Institute for Economic Affairs have all previously received undisclosed funding from tobacco companies, and all have produced research that was then used to lobby against stronger anti-smoking regulations. We found that the Adam Smith Institute has created a structure so opaque that it concealed not only who gave money, but also who took it, leaving us unable to determine where close to one million pounds given by American donors had ended up. Meanwhile, Policy Exchange has previously used evidence that appears to have been fabricated; the resulting report led to fake news headlines in several media outlets that had naively trusted “research” conducted by an opaque think tank.

Opaque ‘think tanks’ working the Westminster lobbying circuit seem to have considerable financial backing. Collectively, they spend more than £22 million of dark money every year to shape public debates and influence politics and policies in Britain. Ironically, some are registered as charities and so are indirectly subsidised by tax payers.

Alarmingly, such opaque organisations not only push out their policy prescriptions via Facebook, Twitter and public events, but they also continue to receive extensive media coverage, including by the BBC. In addition, research published by think tanks regularly finds its way into the academic literature. If academics do not check the source’s funding transparency beforehand, this opens the door to idea laundering.

So, is the influence of think tanks on democratic politics benign or malign? We believe that overall, think tanks – including those that are overtly ideological – make a positive contribution to debates and decision-making in the UK. After all, 17 of the 27 think tanks we assessed are considered transparent, and many produce excellent research. At the same time, this positive contribution is undermined by a minority of opaque outfits that threaten to give think tanks as a whole a bad name.

Transparify’s ratings enable citizens, researchers, journalists, and decision-makers to distinguish legitimate policy voices from dubious sources of ‘expertise’. We hope that the report will move the debate about think tanks beyond the good-versus-evil dichotomies of the past, and instead spark a nuanced debate about what kind of think tanks we want to have influence on democratic politics, and how the media in particular can avoid giving traction to soundbites and policy prescriptions produced by opaque organisations of questionable intellectual independence and integrity.