In our previous articles we have covered different aspects of the design, validation and development of a research agenda. One may have broad topics and focus areas in your agenda to guide the organisation in the middle and long term, but within this agenda, how can one choose a specific and well-timed policy problem to focus the researchers’ and think tanks’ attention on a specific project, publication or event?

This article presents a method that can be used by a researcher, a team or a think tank to understand the specific policy problem that their project, programme or initiative will tackle and plan their research and policy influence activities accordingly. The method links three concepts: policy problem with policy influence with the roles of research. Linking them will aid in maintaining a realistic objective of policy influence while doing the research.

Thinking about the policy problem

The method for analysing policy problems in this post is ideal to take forward during the launch or implementation of a program or project. This is important because it may happen that, by inertia, you start carrying out the actions and activities that have proven successful in the past, or the ones that you are more comfortable with. Nonetheless, problems are not always the same, and it is possible that if you are able to very clearly define a problem taking into account how others perceive it or not, you will find that you can react differently and be better prepared to face it. For this we borrow the academic work on policy problems and use it as a background to develop more concrete ideas about how to plan your research projects in these different scenarios.

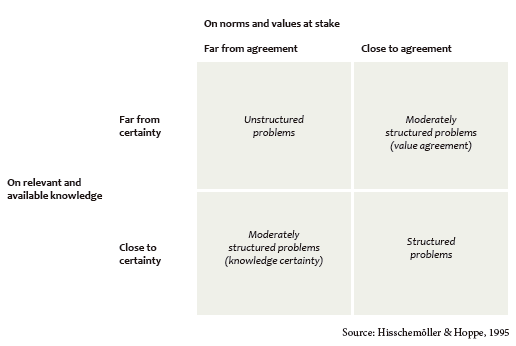

Hisschemöller and Hoppe have elaborated a simple but powerful categorisation of policy problems. For this categorization, two dimensions are used:

- The relevant and available knowledge: refers to whether there is or not certainty in regards to the knowledge available about the problem; and

- The norms and values at stake: refers to whether there is agreement in relation to the values linked to the problem.

This classification refers to both a technical and a political (or cultural) perspective of policy problems. With these two categories in mind, four possible types of problems emerge:

- Structured problems: These are cases where the problem is clearly defined, there is someone in charge of solving it and a general agreement of what this solution would entail. These are many times considered technical problems where experts can play an important role in providing a solution. Examples of these problems could include regulations of health services and road maintenance.

- Unstructured problems: These problems are the opposite of the former and are sometimes labeled as “wicked”, “ill-structured” and “messy”. These problems are complex: there are no clear boundaries, no specific actor responsible for solving them. There are conflicting values and knowledge that are part of an extensive debate. According to Hisschemöller and Hoppe “solving an unstructured problem requires problem structuring, which is essentially a political activity, to produce new insights on what the problem is about.” Examples of this type might include the consolidation or separation of states, negative impacts of new technologies or climate change or complex democratic reform processes.

- Moderately Unstructured problems (lack of agreement on values): In these problems, there is a general confidence about the technical aspect of the problem, meaning certainty in relation to the knowledge, but no agreement on the values involved in the problem. These include, for example, issues such as how to implement a new program to support entrepreneurs or sexual education in public schools.

- Moderately Unstructured problems (uncertainty of knowledge): In these problems, there is agreement on the values, but no certainty about the knowledge or the technical aspect of the problem. An example of this problem is how to tackle HIV-AIDS. Another example of this might be the situation where there is a significant educated or youth brain drain from a country. The general opinion is that this should be stopped, but there is not a clear understanding of why it is occurring or how to tackle it.

It is not feasible to tackle the different types of problems in the same way and the policy influence you are likely to observe might look very differently in each case. For example, tackling a well-structured problem such as deploying a vaccination program is quite different from reaching an international agreement on climate change, an unstructured problem. When you face the different types of problems you should also expect your policy influence strategy to look differently. A policy cannot be implemented right away in all cases, but that does not mean there are no other ways of influencing.

Consequently, the type of research that each problem requires, and that is feasible will vary substantially between these different problems.

For each type of problem two key questions are asked:

- What type of policy influence is likely to occur? What can we realistically expect to achieve?

- And what is the role of research?

The framework is summarised in the table below:

| Structured | Moderately structured problems (value agreement) | Moderately structured problems (knowledge certainty) | Unstructured | |

| Description | Stakeholders are ready to tackle the issue | Stakeholders share values, but have opposing knowledge. | Stakeholders do not agree on their values or priorities | Wicked: stakeholders do not know where to start. |

| What is the role of research? | Show clear options for policy design and how an idea can be implemented:

|

Make sense of existing knowledge:

|

Bring stakeholders together, find common ground among stakeholders:

|

Structure (‘domesticate’) or prioritize parts of the problem to move forward:

|

This framework presents a practical way of connecting a clear objective with the specific context and the type of research to carry out. In each section, there is a direct link between the type of problem, what is feasible to achieve in terms of policy influence, and how research can help.

Previous

Previous