Top take-away:

- The ‘Brussels bubble’ creates a unique environment; many think tanks focus on engagement and events rather than deep research analysis.

- Change happens quickly in Brussels; think tanks tend to be reactive to the day’s issue and go wherever the money is.

- The European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) , is viewed by many as the go-to think tank in Brussels for development policy issues.

Jump to:

- Overview of the EC/Brussels think tank landscape

- City context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Funding sources

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of the EC/Brussels think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory.+

- Total number of think tanks: 45

- Average age of think tanks: 23 years

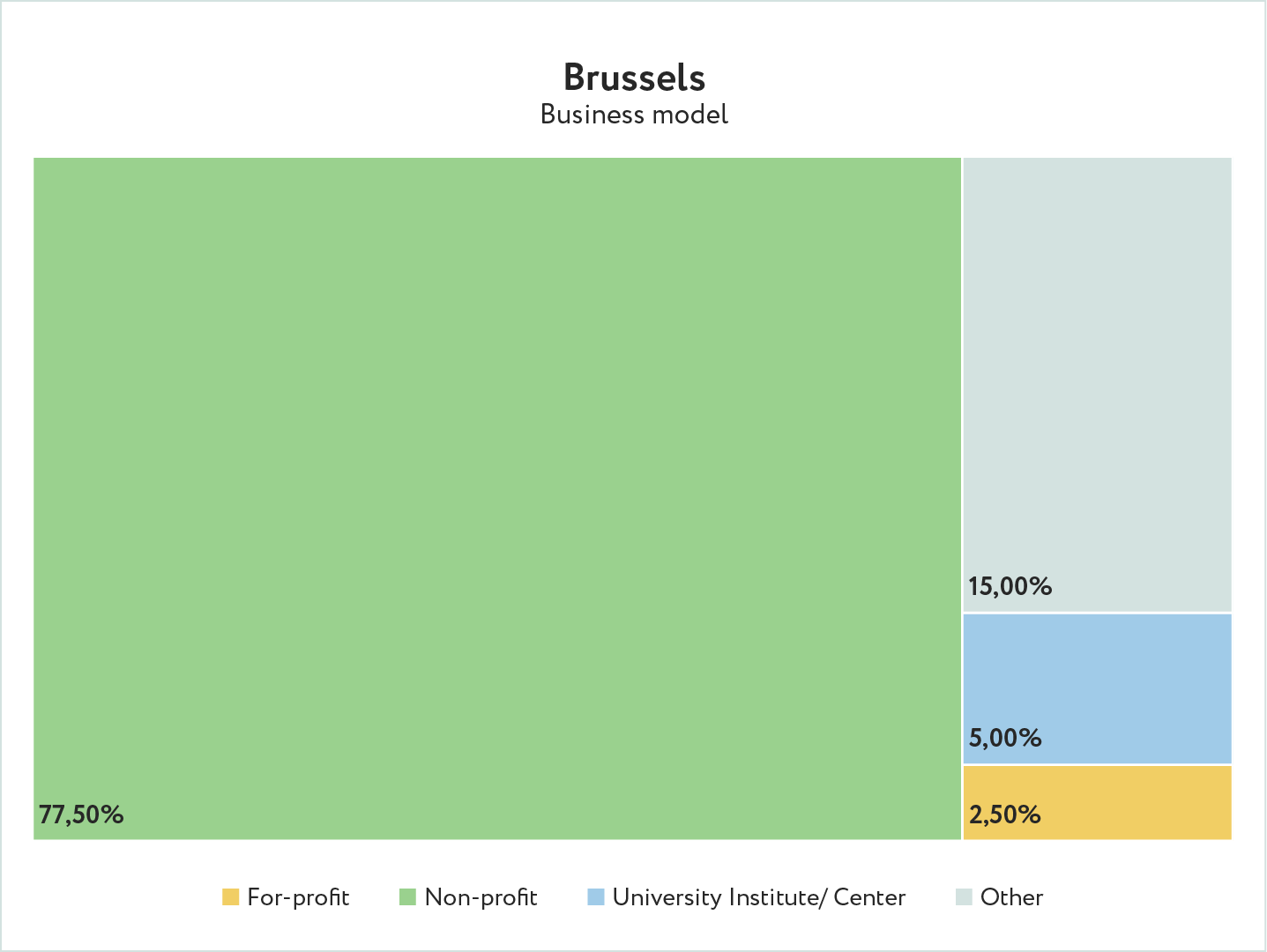

- Business models: Non-profit (68.80%), university institute/centre (4.4%) & for-profit (2.22%)

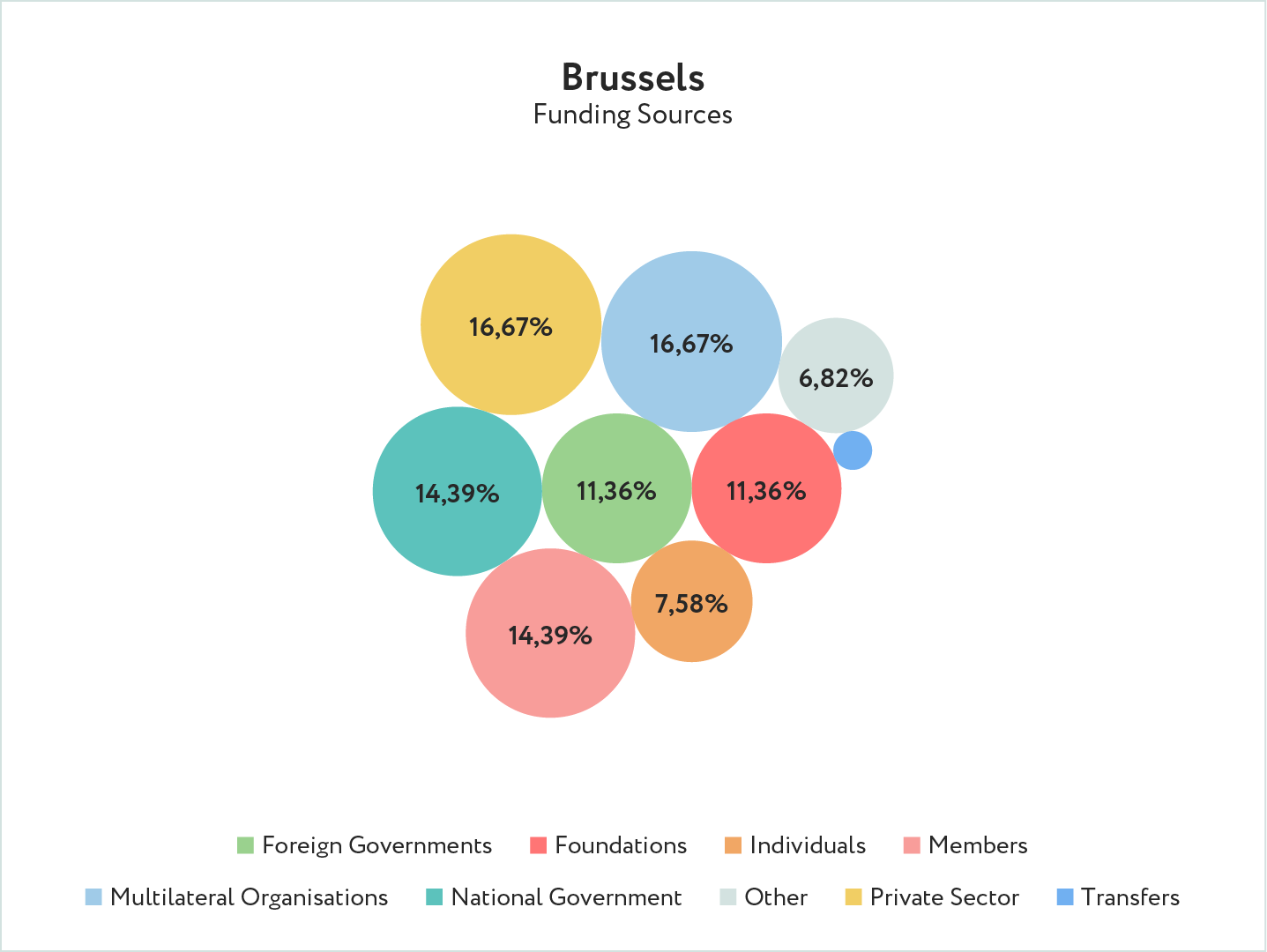

- Top three funding sources: Multilateral organisations & private sector (48.88%), members & national governments (42.22%) & foreign governments (33.33%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks were founded between 2000 and 2019

- Staff size: 30% of think tanks have 11–20 staff members

- Leader’s gender: Male (75% ), female (22.5%) & both male and female (more than one person) (2.5%)

- Average % of female staff: 50%

City context

Brussels is situated in a unique context given the structure of the European Commission (EC), the services that fall under it and the role played by the EU president.

The think tank marketplace is considered newer, compared to Washington, DC and London, and is mainly targeted at the EU institutions.

A new president brings new priorities, and under Ursula von der Leyen these have included the European Green Deal, the EU digital strategy, jobs and growth, a stronger Europe in the world, the rule of law, and democracy.

As the largest donor in the world, the European Union has 79.5 billion euros committed to its international cooperation and development efforts under the Development and International Cooperation Instrument.

The Brussels market varies greatly from others, such as the UK and the Netherlands, given the Brussels bubble and the fact that it is viewed by many as quite elite. The focus tends to be on process rather than content, which makes for complicated procedures and a need to understand how the “machinery” works.

Think tank characteristics

Think tanks play an important role in the Brussels landscape, although there are relatively few of them compared to Washington, DC.

The think tank business model is challenged by how change happens in Brussels, where think tanks often tend to be reactive to the issue of the day if that is where the money is. This is despite the fact that policy change is, of course, a long-term endeavour.

While many think tanks focus on public engagement and events, it was noted the need to work at the technical, political and diplomatic levels to achieve change, in addition to a focus on outreach efforts. In the EC environment it is essential to remain relevant and demonstrate competitiveness with others.

There are typically four types of think tank in Brussels: EU policy institutes headquartered in Brussels (funded by EU programmes, private institutions and foundations, and membership fees); branches of American think tanks; internal EU advisory organisations; and think tanks from EU member-states with offices in Brussels (with government funding from other countries). +

As seen in the diagram below, the dominant business model for EC think tanks is to be registered as non-profit (77.5%); the Other category likely includes the internal EU advisory organisations and think tanks from EU member-states (15%); while only 5% of think tanks are affiliated with universities.

Brussels is seen by some as a think tank “desert”; it is strong on the institutional side, but less so on the academic or intellectual side. In this landscape the ECDPM is often viewed as the one institution that can be likened to think tanks such as the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and the Centre for Global Development (CGD). The Brussels bubble creates a unique environment for the think tanks operating there. Respondents noted that the ECDPM is very strong – and good at what it does – while at the same time responding to the dynamics of this system, with the limitations that come with it.

The term “revolving door” does not seem to resonate given the context. In terms of networks of influence, the entire Brussels bubble is viewed as one large network of influence. One example of a network of think tanks is the European Think Tank Group (ETTG), which is led by the ECDPM. The ETTG is a network of six leading European think tanks. + with 350 policy researchers working on EU international cooperation for global sustainable development. The nature of this network allows for linkages between think tanks in European capital cities and those in Brussels, and between the external and internal policies of the EU. Another example of a network operating in this landscape is Eurodad, the European Network on Debt and Development, a network of 60 civil society organisations from 29 European countries working for changes to global and European policies, institutions, rules and structures in order to reduce poverty and promote human rights.

The EU has a gender action plan and, as such, quite a few events take place in relation to gender, women, peace and security. +

On pandemic preparedness, the ECDPM noted that it had recently developed a paper on this topic because there was no one else covering it, despite not viewing itself as a global health organisation.

There does not appear to be a great deal of work on the R&D side in relation to health and agriculture. Overall, Brussels think tanks tend to focus on foreign and security policy. Among those surveyed, it was noted that due to the diversity of highly complex issues in this area, good research is best done in alliances and partnerships with African think tanks and other actors. They believe this would help to add value and strengthen the Brussels scene.

Funding sources

There is no one funding model predominant in Brussels; rather, there is a richness and diversity in sources of funding. Many think tanks compete with one another for funding and have to fight to obtain a minimal level of financial support. As a result, many are tempted into becoming consultancies.

As one example of a think tank’s funding sources, Bruegel (further detail below) currently uses a membership and project-based approach to funding; the membership fee is 50,000 euros, which is the highest in town. Uniquely, it also receives funding from European member states, who pay based on population size and GDP, and therefore has direct relationships with governments and ministries (whereas other think tanks typically focus on involving member states through embassies). It also receives funding from central banks and corporations, and claims to maintain independence by not working with other private sector groups. It caps European projects at 15–20% of the budget in order to ensure that it is not a ‘think tank of the EU’. The visual here illustrates the diversity of funding sources based on data from the Open Think Tank Directory.

In the ECDPM’s case, 60% of its funding is flexible, while 40% is market funding (involving going to tender or working in consortia). It finds this to be a strong balance as the 60% of funding that is flexible allows it autonomy and independence. It claimed that this allowed it to take the initiative to anticipate policy debates while the other 40% can be used to explore other opportunities. In contrast, it noted that many think tanks are not well-balanced and are either overfunded, and not using the money effectively, or are under pressure to get funding and as such become loyal to short-term contracts.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Brussels think tanks are generally viewed as relevant actors by politicians and policymakers, and as such there is an opportunity for close contact. Most think tanks tend to focus on publications and events aimed at influencing the European debate, and there is typically a positive attitude towards think tanks on the part of EU institutions.

All major think tanks typically host a large annual conference as a flagship event. Bruegel shared that it focuses on EC trends and publishes memos to the European Commissioners every seven years before final interviews with parliament as a means of trying to set the agenda rather than simply following the Commission’s agenda.

Overall there were concerns that some think tanks rely too heavily on events; they could as such be viewed as having limited field experience and direct links with policymakers that lead to hollow policy recommendations. Building a critical mass in Europe requires significant levels of engagement as well as analytical depth in the research, and requires going beyond hosting events.

That being said, some organisations, such as Friends of Europe, are well-known for their ability to engage individuals like EU officials, diplomats and media representatives at their events. While there was some apprehension that this group might have too strong of an advocacy focus, they can co-exist with those who have different business models and may pursue a stronger research agenda.

Previous

Previous