Top take-aways:

- The private sector dominates; there is limited non-governmental organisation (NGO) influence or support for think tanks.

- Mainstream politicians do not tend to focus on official development assistance (ODA) or related issues, despite Japan being the largest development aid donor country in absolute terms in Asia.

- There is no revolving door culture between think tanks and the government.

- Historically the Japanese tend to favour seniority and lifelong employment, and senior male figures tend to dominate; however, this may be changing with younger generations.

Jump to:

- Overview of the Japan think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Funding sources

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of Japan’s think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 81

- Average age of think tanks: 35 years

- Top three cities: Tokyo (49 think tanks), Kyoto, Nagoya & Fukuoka (3 think tanks each)

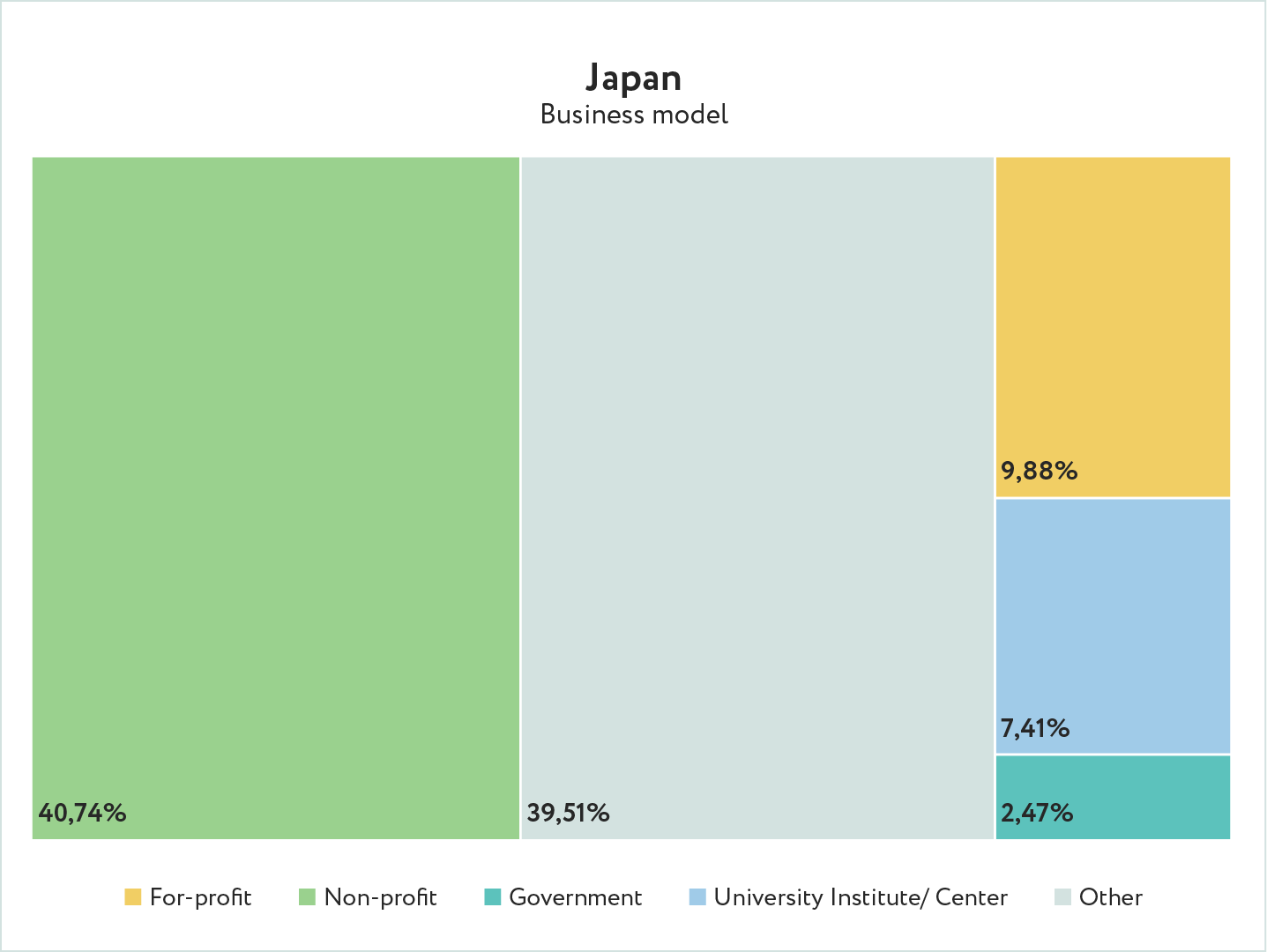

- Business models: Non-profit (40.74%), other (39.51%), for-profit (9.88%), university institute/centre (7.4%) & government (2.47%)

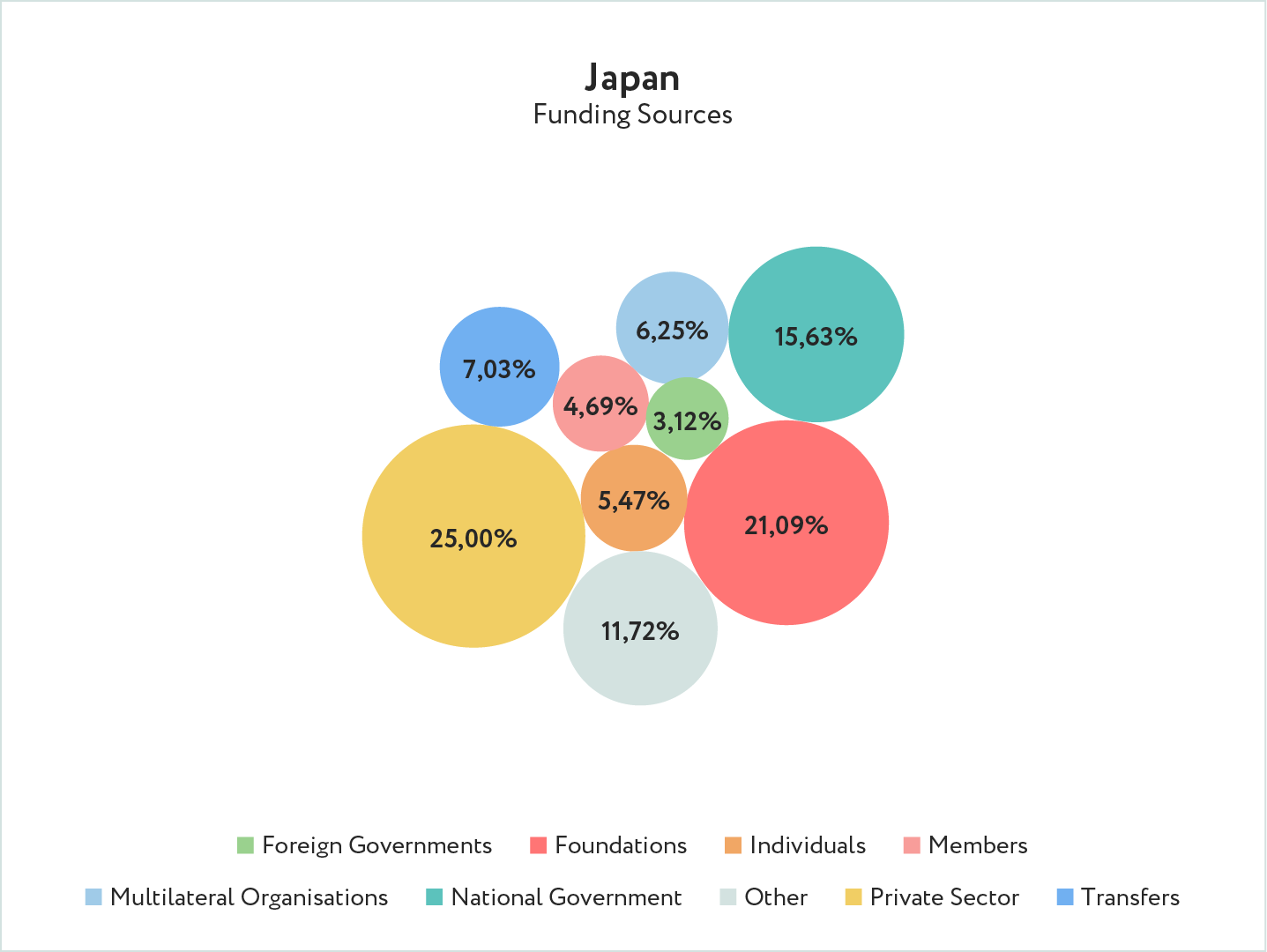

- Top three funding sources: Private sector (25%), foundations (21.09%) & national governments (15.63%)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in Japan were founded between 1989 and 2009

- Staff size: 34.43% of think tanks in Japan have between 21 and 45 staff members

- Leaders’ gender: Male (93.15% ) & female (6.85%)

- Average percentage of female staff: 7%

Country context

With the third largest economy in the world and a population of over 125 million, Japan’s prime minister, Fumio Kishida, has been in place since October 2021 and was previously the president of the Liberal Democratic Party. Kishida is seen as someone who is working to create a new form of capitalism that involves building a stronger middle class, ensuring equal pay, addressing income inequality, and championing universal health coverage.

The administration is typically viewed as stable in Japan and does not change frequently; as a result, the same politicians and policymakers tend to stay in power and create policies. However, following the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and given the current COVID-19 context, there is also a growing awareness that the government is not always correct, particularly when it comes to geo-economic challenges.

Typically, mainstream politicians do not tend to focus on policies that support ODA or a broader ODA agenda, which is seemingly not viewed as a popular agenda or one that most citizens would support. There is, however, a small ecosystem of globally minded leaders engaged in global health decision-making. As in Korea, when it comes to ODA/development issues the government does not tend to rely on think tanks and the think tank sector seems to be viewed as relatively weak compared to other countries. The exception to this is large privately funded think tanks, such as Mitsubishi Research Institute (MRI), which are viewed as powerful actors.

Unlike in North America and Europe, NGOs are not viewed as influential in Japan and do not have a strong voice. Instead, the private sector dominates and government actors are keen to ensure that Japanese companies are supported (e.g. via procurement opportunities).

There is little to no revolving door culture between think tanks and the government in Japan. The same politicians and policymakers tend to keep the power to craft and implement policy. The Japanese government is influenced by the United States when it comes to its development policy and financial decision-making. One such example is its encouragement for global health investments including championing universal health coverage, increased support to Gavi and the distribution of vaccines. Many Japanese pharmaceutical companies are also working on global health.

Think tank characteristics

Despite having a total of 81 think tanks (as recorded in the OTTD), Japan’s think tank landscape is not a dynamic one. Given that there is currently limited funding for these organisations and not a great deal of philanthropy in Japan, there is, however, the potential for funders like the BMGF to have a major impact and make a systematic change to the funding landscape.

Various cultural aspects shape the Japanese think tank ecosystem. Age in Japan plays a role in terms of hierarchy, and seniority is highly respected. As such, senior male figures tend to dominate, although one respondent felt that this may be waning. There are “masterminds”, such as Professor Keizo Takemi, current ambassador to the World Health Organization and known for his network and knowledge around policymaking, who are very well positioned in the health policy area.

As the Japanese culture strongly values respect for elders and their wisdom, younger researchers can lag behind and well-established senior positions may disadvantage other younger actors. This is one Japanese trait that may prevent a dynamic ecosystem from flourishing, although it does present a potential opportunity to explore working with new/younger think tanks. Younger think tankers may possess the ability to advocate more effectively while more senior staff may be more hesitant to communicate directly with the government.

In terms of thematic research, global health (which is generally understood to comprise pandemic preparedness, R&D and DPAF) is a large focus. While one respondent stated that gender equality was a top issue for Japanese think tanks as every think tank is doing something around this topic, another claimed that gender equality is not a priority yet as it is considered a domestic issue and is not reflected in ODA. Innovation and national security are also viewed as hot topics in Japan right now. One think tank respondent noted: “These days we have a lot of emerging technology and have to pay attention to basic science in the context of national security. We are starting to think about how we can protect basic research. One of the biggest reasons that the US pays attention to Japan is in the context of national security. The US tells us to protect scientific knowledge and that R&D is important.”

One example of a network of influence (US, Australia, India and Japan) has emerged: the Quad Tech Network is an Australian government initiative to promote track-2 research and public dialogue on cyber and critical technology issues relevant to the Indo-Pacific region. As part of the initiative, research institutions in Australia (the National Security College at The Australian National University), India (the Observer Research Foundation), Japan (the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies) and the United States (Center for a New American Security) have commissioned papers on key issues facing the region, particularly cyber security and national security.

Funding sources

Japanese think tanks rely on funding from government, companies, foundations, and individual donors. Some think tanks are directly affiliated with private enterprises, such as the Mitsubishi Research Institute, and as such receive funding directly from these companies.

Many others, such as the Asia Pacific Initiative and the Health and Global Policy Institute (further details follow), are set up as independent public non-profit institutions as illustrated in the diagram below. According to one respondent this means they are recognised as a public interest independent organisation by the government and are completely independent.

For those think tanks registered as non-profits and receiving donations from individuals, corporations and foundations, there is fiscal transparency given their need to publish financial records to be legally recognised in this category (and receive accompanying tax incentives).

For independent think tanks, funding typically comes from founders (as in the case of API and iHouse), individual donors, the private sector, and in some cases government actors such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Think tanks are often membership-based and receive corporate and individual membership fees as well as funding for specific projects. At API, for example, to maintain independence the think tank ensures that no one funder contributes to more than 5% of revenue. Through their corporate membership model companies typically donate USD 30,000 per year and may additionally support specific projects.

Overall, the funding landscape appears to be becoming increasingly competitive as think tanks compete for limited funds in an economy that has grown weaker in the past 20 years. One respondent noted that there is not much prospect of increasing funding from corporate members or private sources.

The visual below illustrates the diversity of funding sources based on data from the Open Think Tank Directory.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Think tanks tend to be distanced from the government; policymaking is quite centralised, and there is not a strong demand for research.

Overall, decision-making networks are small. While Japanese think tanks would, of course, like to have the power to influence the policy process, this is not common. Overall, policymaking is quite centralised in Kasumigaseki, the Tokyo district where most government ministries are located, and there is no strong demand for research. Unlike in North America and Europe, NGOs are not viewed as influential in Japan and do not have a strong voice.

Previous

Previous