Top take-aways:

- The Netherlands’ most influential think tanks are either embedded in the public system or close to the government, with not many that dare to step outside the government agenda .

- The three central planning bureaus (Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and the Social and Cultural Planning Office of the Netherlands) are influential. Their links with policymakers are close but they also assert their independence.

- The scientific reputation in the Netherlands is so important that even planning bureaus carefully manage their boundaries, with policy and politics remaining neutral.

- In foreign and EU affairs, university institutions and research groups are the most in-demand by parliamentary committees to help develop policy and independent think tanks such as the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and the Clingendael Institute.

Jump to:

- Overview of the Netherlands’ think tank landscape

- Country context

- Think tanks characteristics

- Funding sources

- Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Overview of the Netherlands’ think tank landscape

Data comes from the Open Think Tank Directory. +

- Total number of think tanks: 37

- Average age of think tanks: 34 years

- Top three cities: The Hague (20 think tanks), Amsterdam (10 think tanks) & Maastricht (2 think tanks)

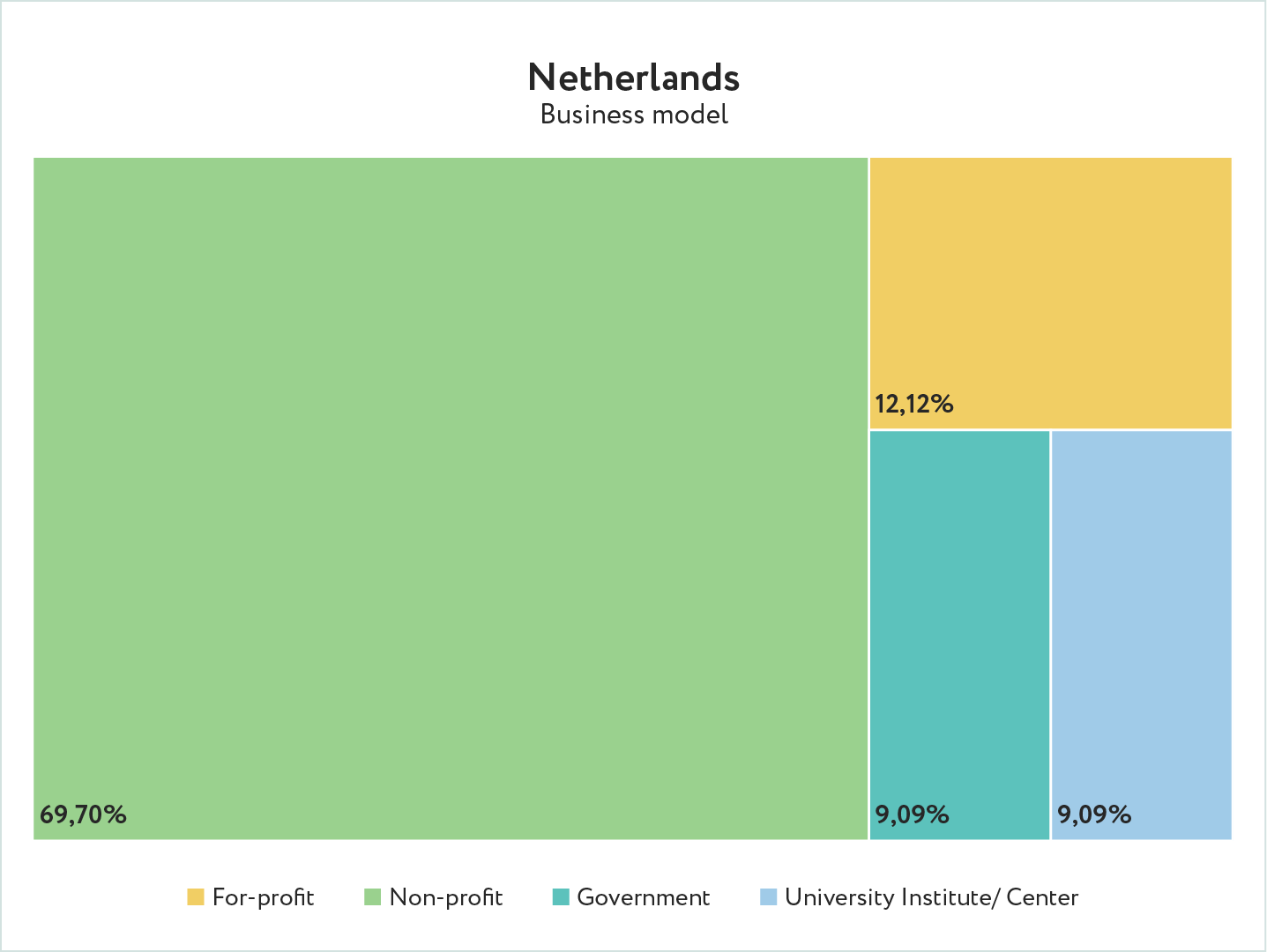

- Business models: Non-profit (69.70%), for-profit (12.12%), university institute/centre (9.09%) & government (9.09%)

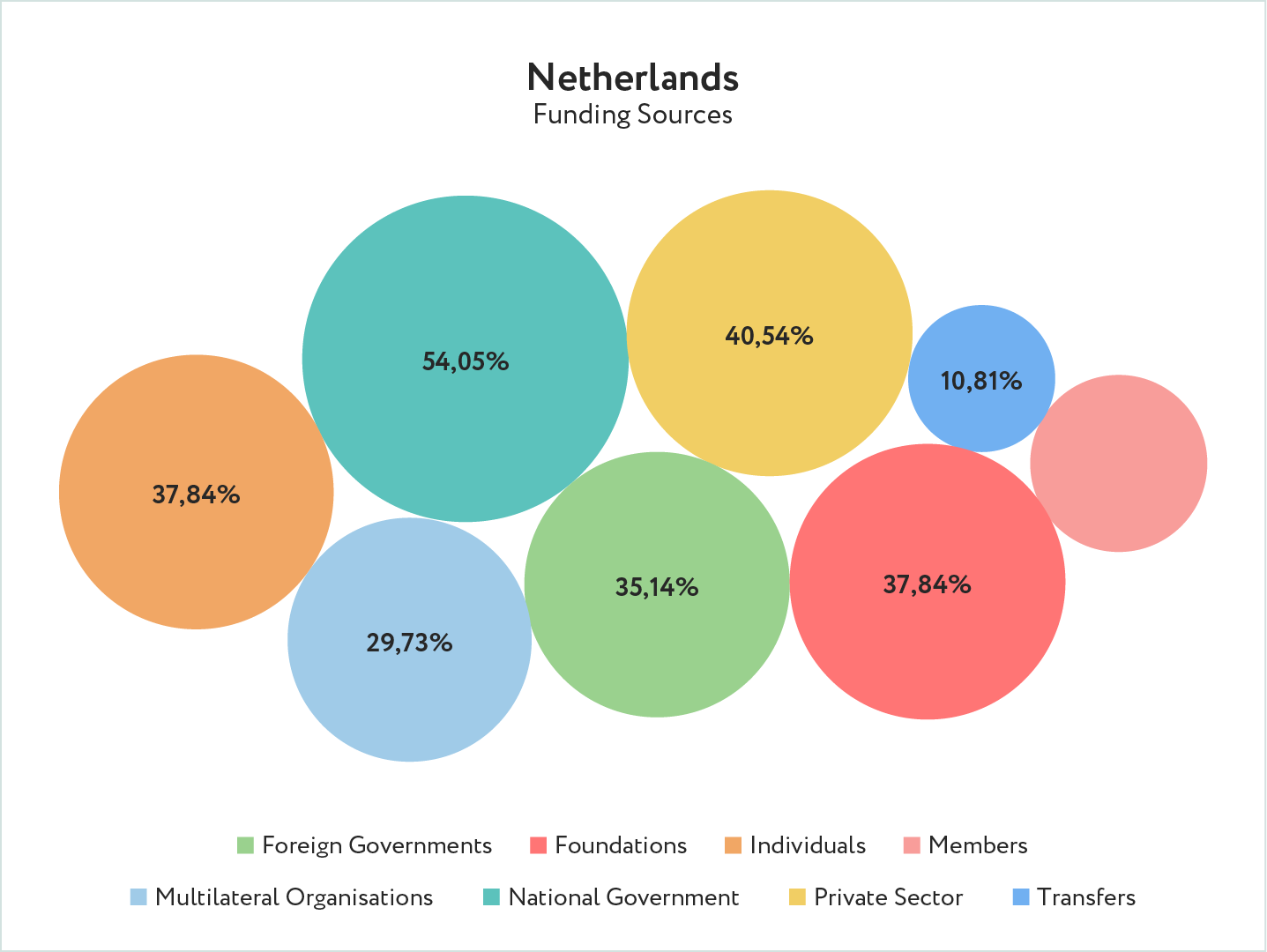

- Top three funding sources: National government (50.05%), private sector (40.54%), foundations & individuals (37.83% each)

- Date founded: Most think tanks in the Netherlands were created between 2000 and 2019

- Staff size: About 28% of think tanks in the Netherlands have up to 10 staff members

- Leader’s gender: Male (64.51% ), female (25.80%) & both (more than one person) (9.67%)

- Average % of female staff: 27%

Country context

The Netherlands’ political landscape is quite fragmented with a strong party coalition tradition. The current government is composed of the dominating conservative-liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), the social-liberal Democrats, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) and the Christian Union (CU). VVD is the leading party in government as it won the Dutch general elections for the fourth time in a row in early 2021.

One remarkable feature of the Dutch political landscape is the Netherlands’ longstanding tradition of its central planning bureaus that date from the 1940s. The Dutch planning bureaus, similar but with more political importance than those in Belgium and France, are knowledge institutes that provide the government with data-driven answers about the present and future state of the country and how it is affected by the government’s policies and decisions. These are government institutes with agency status that fall under the authority of the executive while at the same time asserting their independent research status. There are also deviations from the dominant technocratic central planning bureau model in the form of advisory bodies such as the Advisory Council on International Affairs (AIV) or the health-focused RIVM, which are also embedded within the government but act as independent bodies.

The Dutch research agenda is also very European in many ways. Policies in the Netherlands are highly influenced by the European Union (EU), especially in areas like peace and security, agriculture, and food security, where EU priorities are decisive. The European Green Deal coupled with the EU’s “Farm to Fork Strategy”, for instance, are very much embedded within the Dutch research priorities. As reported by interviewees, this alignment in research agendas is one way the Netherlands research ecosystem differs from the rest. It was also reported by interviewees that in the 2010s the country decided to have a decentralised network of thinkers organised around food security and agriculture. One example is the multidisciplinary “Netherlands Food Partnership”, which is reported to be the network of influence on food policy.

Dutch think tanks are very interested in the research thematic of development policy and finance, followed by agricultural research and innovation, which are of natural relevance to the Dutch domestic context, and global health. Another key topic for most of the Netherlands’s internationalised Dutch institutions and external policy actors is “gender”. There are NGOs (i.e. Mama Cash, Wonda Collective) and many more internationally connected gender networks active in the Netherlands working with and for women around the world. The Rutgers Foundation, for instance, has been quite active in sexual and reproductive health both in the Netherlands and beyond.

Compared to other European countries, there is more of a revolving-door culture in the Netherlands, as experts in the planning bureaus or scientific institutes may move into a government department or a policy position within a party.

Think tank characteristics

Three main types of think tanks are closely linked to the government but that engage and relate differently with policymakers: central planning bureaus, advisory/consultative bodies, and political parties’ scientific bureaus.

The ones closest to the government institutions are the central planning bureaus. Currently, there are three planning bureaus established in the country: one that provides advice for economic policy (CPB, Centraal Planbureau, or the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis); one giving advice for environmental and nature conservation policy (MNP, Milieuen Natuurplanbureau, or the Netherlands Environmental Assess-ment Agency), and one dedicated to social policy (Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, or the Social and Cultural Planning Office of the Netherlands).

Together, these bureaus produce numerous reports and give day-to-day advice to policymakers on many issues (i.e. women with children participation in the labour market, short-term economic forecasts, target monitoring of environmental policy, etc). They even provide specific data to international organisations such as the European Environmental Agency or the International Panel on Climate Change, but it should also be mentioned that the central planning bureaus’ “external assignments” are limited to local and national governments, European institutions or international governmental organisations.

As reported by interviewees, it is clear that the links with policymakers are close and that the policy relevance of advice is prominent in the bureaus’ research programme. Planning bureaus provide the relevant economic assessments that form the basis of public finance projections by the finance ministry, hence their assessments feed straight into the government’s budget while preserving boundaries with policy and politics and remaining neutral by safeguarding their independence.

The economic planning-focused CPB, for instance, being the oldest and the most consolidated planning bureau, has a close relationship to policymakers, in particular the civil servants at the departments of finance and economic affairs. While the CBP remains independent, personal linkages among its staff with government departments and a shared education background facilitate regular contacts during the elaboration of reports. This leaves a space to discuss the main issues to be addressed in the report and exchange data for the presentation of results. As a result, other research organisations find it very difficult to compete with the central planning bureaus, especially taking into consideration the data privileges and the accumulated calculative resources that the planning bureaus own. Key reports of the central planning bureaus also get prominent media attention and are in most cases presented as unquestioned assessments of the state of affairs.

Other examples of government advisory bodies with autonomous mandates are the Onderwijsraad (the Education Council), which gives advice to the minister, parliament and local authorities on education matters. Meanwhile, the Health Council of the Netherlands and the RIVM have been tasked with scientifically advising the government and parliament about matters of great importance in the areas of public health, such as the formal role of the application of medicine in the country and decisions related to what should be government funded. A similar mandate has the Advisory Council on International Affairs (AIV), which serves as the traditional anchor of Dutch foreign policy.

The third type of think tanks that are close to the government are political-party-affiliated scientific bureaus. These include Teldersstichting (affiliated to the centre-right VVD party), the Wiardi Beckman Stichting (linked to the centre-left Labour Party), and the Bureau De Helling (linked to the centre-left green political party “GroenLinks”). This type of think tank is directly linked to a political affiliation and abides within the frameworks set by its own party leadership. With no particular overarching thematic agenda, these organisations usually produce ad hoc qualitative reports, which differentiates them from the central planning bureaus’ quantitative-based research. Scientific bureaus usually have prominent leaders appointed for their civil society trajectory/reputation, and their networks are typically politically strong.

Aside from the “government think tanks” and outside of the government’s agenda there are also a number of independent and academic think tanks hosted by universities like the Wageningen University & Research. Private research institutions such as the conservative Edmund Burke Foundation or think tanks like the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and the Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael) are also part of the independent think tank category. Furthermore, within the Hague’s historic tradition of international peace promotion and conflict prevention sit institutions like the Hague Institute for Global Justice, Peace and Security.

The following table shows how a majority of think tanks are formally established as non-profits, with only a small percentage conceived as for-profit organisations.

Funding sources

The central planning bureaus and the advisory bodies are largely publicly financed (a maximum of 20% of their annual budget may originate from limited external assignments), and the scientific bureaus linked to political parties are also government funded. In the Netherlands, all political parties that have seats in the House of Representatives are eligible to receive government subsidies to set up their own think tank.

While more than half of Dutch think tanks receive funding from the national government (see table), funding sources are also very varied, especially for the non-governmental think tanks. The Edmund Burke Foundation (centre-right), for instance, together with Stichting Waterland (left wing), are entirely dependent on private donations, while the Clingendael Institute receives great part of its funding from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Defence. University research groups within universities and NGOs also draw on government funding. Other think tanks like the National Think Tank Foundation report having private commercial sponsors like McKinsey & Company to fund their social impact programme. In contrast, the independent think tank Kennisland is mainly funded by project grants sponsored by different actors (i.e. Hivos, the EU, city councils) covering health and education innovation initiatives.

Demand for evidence and influence on policy and public debate

Central bureaus have the dual role of being trusted advisers of the government while remaining independent and not politically aligned. The three big central planning bureaus are at the Netherlands’ core policy advising. Most of the time, their reports are unquestioned and regarded as the leading opinion by almost all stakeholders in the public space. They are both influential to the public debate and politically, as public decisions are mainly shaped by these reports.

A usual initial procedure when the government asks for parliamentary advice is to have the parliament consult the central planning bureaus in advance and commission them to research a certain matter. Political parties, too, have their election programmes assessed by the central planning bureaus before going into elections. The planning bureaus calculate the potential effects on different domestic issues, hence exercising a certain degree of influence into the content of the political offer. On the other hand, scientific institutes linked to political parties inform the Dutch public debate on relevant domestic issues like the welfare system.

As reported by an interviewee, advisory bodies embedded in government, such as the Advisory Council on International Affairs (AIV), have the strong listening capacities and are good at synthesising what other actors in the foreign affairs field propose. The AIV is said to serve as an influential platform to consolidate ideas, but at a time when decisions have already been made. More important and influential is the source whose ideas are utilised by the ministry’s staff before decisions are made. In the foreign affairs field, this role is played by independent think tanks, university institutions or research groups that have direct contacts with ministries, such as the Clingendael Institute. These more academically orientated organisations get invited to consultations and parliamentary meetings where the policies are developed. The Transnational Institute, for instance, is reported to manage to pick out the right topics that are useful for both domestic debates and in the European parliament. More recently, a network called the Red Team emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, gathering a group of experts who organised themselves to be critical of pandemic measures. They were invited by the permanent parliamentary committee for a round table discussion, where the Red Team gave a briefing and answered questions from committee members.

Many networks that seek influence target speechwriters and the top advisors to the ministers as these do not change when a political cycle ends (politically, they don’t change, they remain). As these advisors remain and political continuity is somewhat guaranteed when someone wants to exert influence on a minister, they target both the minister and their advisors.

Previous

Previous